Here Is What American Workers Need in a Secretary of Labor

We need a national labor leader today who understands that there is no real choice between addressing the immediate impacts of current crises and striving for economic and social justice. We must accomplish both, because the two are inextricably linked.

As the Biden–Harris team transitions from campaigning to governing, and begins to appoint and nominate its senior officials, there has been increasing pressure on them to focus on diversity, as well as to deliver on the promises made to the diverse groups that played a critical role in electing them. There have also been calls for the new administration to not fall into the trap of returning to “normalcy” post-Trump, and post-pandemic. While normalcy is a message that the campaign ran on, it’s an illusion, one that overlooks the plight of low-income individuals, immigrants, many communities of color, and those falling into the intersections of all of the above. For them, “normal” life even before the pandemic meant unemployment, low wages and low-quality work, and a lack of quality education and health care. As the pandemic, resulting economic recession, and recent wave of racial justice reckoning have laid bare, our systems and institutions have been failing and broken for decades, and have been rooted in systemic racism, discrimination, and policies that have largely favored the privileged and powerful.

What can the new administration do to right these wrongs, and embark on a future that’s bright for everyone?

What America Needs in Its Secretary of Labor

Many, including within the labor movement, the Democratic party, and progressive groups, are debating and speculating about the administration’s appointment for the next secretary of labor, and the requisite qualities for someone to adequately fulfill the role—diversity, again, being among them. Irrespective of the names mentioned so far, I would argue that the three following qualities are the most important—across cabinet and sub-cabinet positions, but especially in a secretary of labor, and especially at this pivotal moment. Without a secretary possessing these qualities, we end up with a symbolic figurehead, and not the leader that all of us need.

First is diversity—in terms of identity as well as lived experiences—which is crucial, particularly at a level as senior as that of secretary. Lived experience runs deeper than which box one checks for race and ethnicity on a survey form: it includes experiences of class and economic disparity, the experiences of family and loved ones, and experiences organizing for a better life, whether professionally or otherwise. Not every labor leader has had a job title that recognizes their efforts. The selection process must pay attention to these details: without diversity in both identity and lived experience, our nation’s labor leader will face some challenges with deeply understanding the issues, which challenges and policies should be centered, and why certain policies failed. It’s not just the name and the face: it’s the path one has walked, as well, that matters.

Lived experience runs deeper than which box one checks for race and ethnicity on a survey form: it includes experiences of class and economic disparity, the experiences of family and loved ones, and experiences organizing for a better life, whether professionally or otherwise.

Second is relevant policy and administrative knowledge, expertise and professional experience—this should go without saying, but unfortunately, as especially recent history has shown us, this has not always been a priority when selecting a labor secretary. As one top-ranking official in one of the nation’s largest unions said in an interview, “We are in the midst of a great labor crisis…We have a collapsed and dysfunctional unemployment system with millions unemployed…and we need to get the minimum wage up to ensure a healthy recovery. Those are technical issues” that personal experience can assist in identifying and addressing, but which requires far more. This experience and knowledge—the understanding of not just what the challenges are, but how federal labor law and the infrastructure of the Labor Department can be used, and improved, to protect the most disempowered workers and reinvigorate the economy—is critical, especially in moments of multiple crises. But it should be in addition to lived experience, not instead of it.

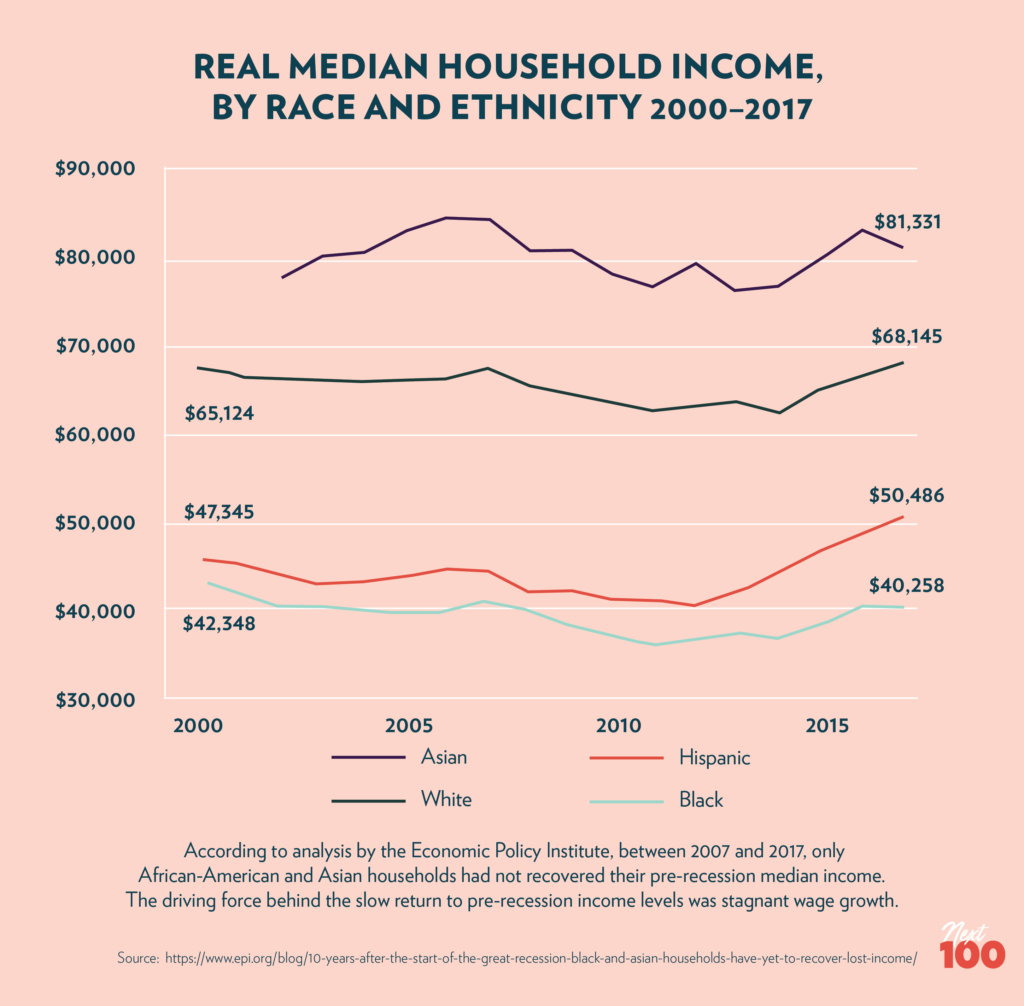

Third, whoever is appointed must also recognize and be equipped to lead with an understanding that their challenge is two-fold. Certainly, we need to recover from the crises that confront us, of which pandemic and the recession are but two. But we must tackle these recoveries in a way that both addresses the recent disproportionate devastation that Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities, in particular, have experienced, and that takes seriously the persisting economic, social, and civil rights injustices that certain groups of workers have experienced for generations. We saw firsthand during the Great Recession how communities of color were forgotten during the recovery. Unemployment rates rose and homeownership rates fell faster for Black and Latinx individuals than any other group, and even ten years after the beginning of the Great Recession, Black and Asian households had still not recovered lost income in the wake of the economic downturn, due to stagnant wage growth. While today’s crises are already taking their toll, going forward, there must be a serious commitment to addressing the causes, solutions, and the interconnected and systemic nature of the challenges, so that we don’t continue using band-aids on mortal wounds. We have a serious public health crisis, an economic crisis, a jobs crisis, a climate crisis, and an education crisis, to name a few. And they are all interconnected.

Going forward, there must be a serious commitment to addressing the causes, solutions, and the interconnected and systemic nature of the challenges, so that we don’t continue using band-aids on mortal wounds.

All three of these qualities (i.e. diversity, relevant professional knowledge and expertise, and a commitment to systemic change) are necessary for the nation’s new secretary of labor if they want to use the power of the Labor Department to drive systemic improvements for workers.

Figure 1

A Leader Fit for the Moment

The crises we now face will not be the last that confront us. Now and into the future, we need leaders at the helm who understand that there is no real choice between addressing the immediate impacts of current crises and striving for economic and social justice. We must do both, because the two are inextricably linked. The means of achieving the ends are just as important as the ends in themselves, because the means will dictate the ends at which we ultimately arrive. This is not just an issue of recovering from the pandemic or of rebuilding infrastructure: it’s also an issue of sustainability and survivability—really, of preserving our humanity. How workers and their families have, and are, being impacted during these crises, and how they are supported (or not) towards recovery, will have lasting impacts on communities, and for generations to come.

Thus, while some issues, like getting enough of a handle on the pandemic to enable everyone to safely return to work, school, and their families, may take precedence in certain respects, we cannot take our eyes off addressing long-standing challenges that predate the latest crises. Our inability to address the systemic inequities have, and are, exacerbating the crises’ impacts on all of us, and have brought us to this critical moment. A new leader at the Department of Labor—as well as other new leaders across the administration—must be able to address both.