Policymakers and Philanthropy Must Empower Workers with Real Authority to Create Lasting Change. Here’s How.

In order for us to achieve progressive systemic change, workers must be engaged in ways that drive key public policy and philanthropy decisions, above and beyond merely providing the popular support needed to make change possible.

Even a cursory glance at the last decade can tell us that our nation’s policies have failed to respond to the needs of the majority of workers, especially those who are of color, young, low-income, and/or from rural areas. We haven’t seen a raise in the federal minimum wage since 2009, and disparities continue to grow across race and gender lines, in many other areas, such as education, health care, and employment. One reason for this has been the weak policy alignment between the majority of workers and the groups who advocate on their behalf in the corridors of power, such as legislators, lobbyists, and philanthropic organizations. A study by scholars from Princeton University found that mass-based membership associations and advocacy groups, including nonprofits and labor organizations, do not represent the policy views and interests of their constituents well and have limited collective influence on policy outcomes.

This is in part because the most pressing issues are not prioritized by those types of organizations. Or, when policies are implemented, they fail to adequately address root-cause issues or to help those who would benefit most from them. These challenges, in turn, are often because we do not have the right people—the workers directly experiencing the challenges—at the public policy table, informing the change process. At times, this is because certain groups are intentionally shut out and not invited to a seat at the table by those in power. However, at other times, those in power make the common mistake of seeing impacted individuals in a limited capacity. They expect them to organize or to “support” a policy change, but don’t necessarily empower them with decision-making authority: to decide where the money goes, and what policies should look like. When workers are involved, it is often at the tail-end of the process when the key decisions have already been made. Workers should be driving systemic policy and philanthropic change, not just expected to make the noise or be the face that makes the change possible.

Workers should be driving systemic policy and philanthropic change, not just expected to make the noise or be the face that makes the change possible.

In reality, the workers who progressive policy and philanthropy look to support are often best positioned to drive and direct change because of their lived experience and proximity to the issues. How the problems are defined and framed—and whose stories and experiences are driving the change process—are just as crucial as the solutions themselves. Gerry Roll, executive director of the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky, emphasized this when she spoke to a group of philanthropy organizations about how they could better fund rural community organizations: “In my opinion, you’re not proximate to our community unless you’re drinking our water, or sending your children to our schools.”

“In my opinion, you’re not proximate to our community unless you’re drinking our water, or sending your children to our schools.”

“Centering workers” is a common refrain in policy and philanthropy conversations, but what does it actually mean, what does it look like in practice, and how close are we to achieving it? For many organizations, especially those serving and organizing workers, this is fundamental to their theories of change. Workers are driving change and directly shaping the work of these organizations in numerous ways, from who is leading and staffing these organizations, to how such organizations support their communities and constituents, to how the policy and advocacy strategies are envisioned and executed.

In this piece, we highlight three ways that workers can be effectively empowered to achieve progressive systemic change: through policy work, philanthropic decision-making, and direct investments in workers and worker organizations to build leadership, organizing, and long-term capacity.

1. Ensure public policies are developed for, by, and with workers by involving them as we engage in policy work, including in problem-solving, solution development, and evaluation.

There is an important difference between public policies that are good for workers but developed by people without direct experience with the issues, and policies that were actually developed by workers who will be impacted by the policy solution and its implementation. While both are positive, including workers in the entire process leads to solutions that are more responsive to their needs. Worker power cannot be built and sustained without including them at this level, in this way. And yet too often, on the progressive side, we focus only on the former, policies that we believe to be good for workers, while only giving lip service to the latter at best.

One way to actually achieve the latter is by talking to workers directly and at scale, asking them not only about their experiences and challenges but also asking for their input on priorities and solutions. The Working Families Party, for example, surveys their members in a variety of ways, including by phone and by leveraging webinars, to understand their perspectives on policies.

This may seem like an obvious practice to follow, but it is unfortunately not nearly common enough, either because those developing solutions don’t believe this to be a critical part of the process or don’t have the direct connections to impacted individuals they need. The outcome is that the solutions are not targeted enough and lack appropriate focus, resulting in diminished impact. This opportunity and challenge—how to include impacted individuals in policy and advocacy in ways that ensure they drive the agenda—is core to our mission and work at Next100, to bring those with lived experience or proximity to communities to the policy table. We have worked with Native American youth, undocumented and mixed-status families, charter school alumni, and the formerly incarcerated; we also work to ensure that these communities have a greater say in government and a better pipeline into government policymaking roles, to ensure stronger public policy.

2. Involve workers in philanthropy by empowering them to play a key decision-making role in how philanthropic assets are used.

Money is power. That is a simple fact. Accordingly, positive and effective philanthropy does more than simply make an impact: it shifts power. Therefore, to empower workers and worker organizations, philanthropists must involve workers and their organizations in decision-making about not only where and how money and resources should be allocated, but also in evaluating the impact and effectiveness of efforts. One way to achieve this is by including workers on philanthropic or programmatic advisory or governing boards, to ensure formal processes for ongoing input and oversight. This can include upfront engagement as well as engagement down the line—for example, including workers in the measurement and evaluation of solutions.

Positive and effective philanthropy does more than simply make an impact: it shifts power.

Not only must we ask workers what solutions would best address their challenges and needs, especially when issue prioritization is necessary: we must also get their feedback on how to measure success. As noted above, ongoing advisory boards can be one means of doing so. The XPERT Worker Advisory Board, a collaboration between New Profit, Goodwill Industries International, and Accenture, helps inform recommendations and investments for the organization’s future of work strategy. XPERTS was established to increase the engagement of frontline workers from racially, ethnically, experientially, and geographically diverse backgrounds in the Future of Work Grand Challenge, an effort to elevate the voices of workers in future-of-work innovation. The XPERTS are not just engaged in the work—they are integrated into it.

The California Endowment’s billion-dollar, ten-year initiative Building Healthy Communities (BHC) is another example of philanthropy that changed its practices to center the people who it aimed to serve. The Endowment’s efforts focused on improving the health of young people in fourteen of the California communities most devastated by health inequities. To center the initiative on the young people impacted, the Endowment engaged youth as key changemakers, inviting them to sit on the BHC steering committee and to advise the Endowment’s president, rather than hiring external “experts” to write briefs.

3. Invest in workers directly, focusing on building stronger, more resilient, and financially sustainable worker organizations.

Building the power, sustainability, and effectiveness of worker-led organizations that are supporting workers ensures that in any form of change, workers are driving it. It means funding activities that enable organizations to have the money, the infrastructure, and the people to do the work over the long term—on their own terms—and the overall capacity to engage in both direct support and organizing work, which includes responding to crises as well as engaging members and communities in policy and advocacy and in other ways that build long-term power.

Jobs with Justice, a national coalition of worker organizations; Brandworkers, a worker center that supports food industry and factory workers; the Disinfo Defense League, a national network of grassroots, community-based organizations and advocacy groups building a collective defense against disinformation campaigns and efforts that deliberately target communities of color and other marginalized groups; and the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization, a “think and do tank” that enables the development of strong worker organizations, are several examples of organizations that focus on investing in, and supporting, worker organizing, resource-building, and leadership development. These organizations believe that workers are the experts, and therefore, uniquely-positioned to lead change.

And yet too often these activities are under-funded and under-resourced in policy and philanthropy, for a variety of reasons. For one, to some funders, the desired outcomes or “returns” on these kinds of efforts are evaluated solely in terms of short-term investments, or disconnected from the on-the-ground realities and challenges. Building individual and collective capacity often requires a longer timetable to see results, and is also one of the most critical areas for building worker power—or any form of power.

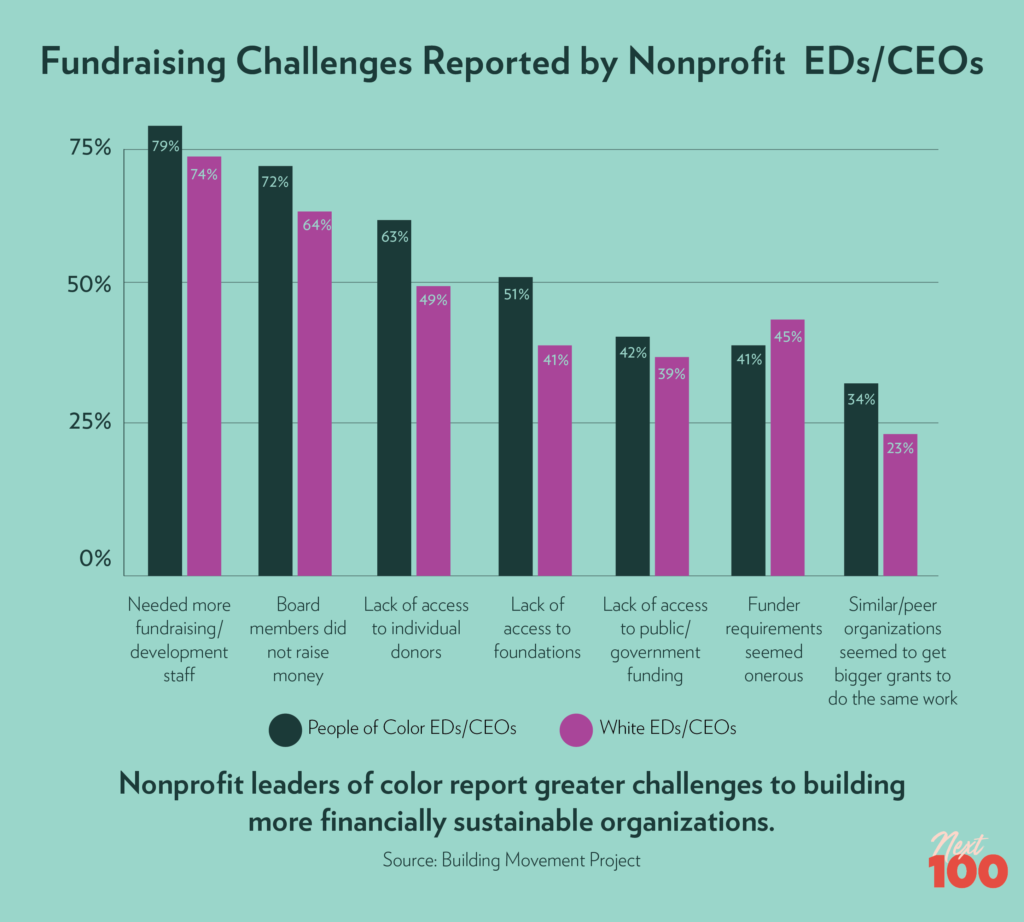

Additionally, at times, the value that worker-led organizations bring is not fully understood. At other times, they have a harder time raising money, especially when led by women and people of color; many strings are often attached to the funds offered to such individuals, limiting their organization’s power and resources. A 2017 report, conducted by the Building Movement Project, showed that leaders of color who have reached the top position in their nonprofit organizations, on average, have smaller budgets to work with and are more likely to report they lack access to (and face challenges securing) financial support from a variety of funding sources than white leaders. Seventy-two percent of leaders of color had board members who did not raise money compared to 64 percent of white leaders; 63 percent of leaders of color reported they lack access to individual donors compared to 49 percent of white leaders; and 51 percent of leaders of color lack access to foundations versus 41 percent of white leaders.

Figure 1

As we consider supporting workers to drive progressive change through policy and philanthropy, we also must acknowledge that workers—especially in communities of color, and women—are already leading the way in a lot of the most critical organizing we are seeing. As Stacey Abrams and Lauren Groh-Wargo wrote in a recent op-ed about the ten-year journey to turn Georgia blue, “organizing is the soul” of building progressive power. We can look at what happened in the 2020 elections, in places like Georgia and other states like Wisconsin, Arizona, and Pennsylvania: what we see demonstrates the essential role of workers and grassroots, community organizations and movements in creating the conditions for change.

It’s Time to Walk the Walk

Ultimately, to empower workers in the way that many of us envision, and to close the systemic disparities that diminish the opportunities and well-being of low-wage workers, workers of color, and women, we have to walk the walk of “centering workers” in systemic change—not just talk the talk. This must be done intentionally and effectively, over and over again, in different spheres. We must put their needs and interests front and center, and also involve them in the process of policy change and philanthropic decision-making from top to bottom. Workers are essential to achieving substantive change: without them playing a leading role, the progressive change that many of us are striving towards is not possible.