Preparing to Protect Workers’ Rights against the Risks of Artificial Intelligence

We should keep a close eye on Illinois’s new Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act, as it raises a host of issues and questions about AI’s role in the workplace. It is the first law to regulate employer use of AI in online hiring—a practice we are likely to see more of in response to the covid-19 pandemic.

Though still little-understood by the public, artificial intelligence (AI), once appearing only in science fiction, now comes up in the news, and our daily lives, every day. And it does so in an ever-increasing array of contexts, and with ever greater levels of impact. Take as an example the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which millions of the social media behemoth’s profiles were mined for data, and the data then used for political ends. For weeks, the nation watched Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, through the media’s microscope, including his delivery of testimony before Congress to explain and justify what had happened. Turns out the incident hadn’t just baffled the average American: it had baffled the average American policymaker, too.

AI can and will have an impact on every aspect of our lives for which data can be gathered—a category from which fewer and fewer realms of experience are finding themselves excluded. Labor has long been under the lens of quantification, and AI’s workplace uses are among the technology’s most well-known applications. Automation replacing jobs, for instance, is a real concern for many Americans, and AI is a component of many automation efforts.

figure 1

But AI’s impact on the workplace, and the issues created by its impact, are much more far-reaching than that. In fact, AI isn’t being used just to replace jobs: it’s also being used to determine

whether or not you’ll get your job in the first place.

AI isn’t being used just to replace jobs: it’s also being used to determine whether or not you’ll get your job in the first place.

In this article, I’ll be discussing exactly that issue—the use of AI in hiring processes, and how policymakers have begun responding to that usage. In this and in articles to come, one of my goals is to illuminate some of the unexpected ways in which technology is complicating our experiences as workers, and how policy can be used to make sure that workers have a say in its influence. As the Cambridge Analytica incident illustrated, our lawmakers have a lot to catch up on; and they need to catch up fast.

What Is AI, Anyway?

Before I get into the policy though, let’s get down to basics. What is AI? How does it work? And why should we care?

Artificial intelligence is a broad term that refers to the use of machines to imitate human intelligence and behaviors such as learning and problem-solving. The term is “broad” in the sense that the applications and uses of AI are manifold, so when we are talking about AI, what it’s doing in the most concrete sense, really depends on the specific purpose and form of the application. However, in general, the AI in use today typically is used to process massive amounts of data, analyze that data, and make suggestions based on these analyses. The “intelligence,” in these cases, is used to supplement (or substitute) our own.

Oftentimes, AI programs are structured in ways that roughly imitate our own brain structures. AI applications are used to automatically gather and analyze enormous amounts of data very quickly; it then uses algorithms (sets of instructions about how to consider data) to discern patterns, and then make a decision or to predict something in the world, based on its cache of trends and probabilities. As with making any prediction based on probability, the more data that is provided for the algorithms, the “better” the AI using those algorithms gets at making decisions or predictions.

Google’s search engine, and Amazon’s product suggestions, are two examples of this activity that many of us have seen in action: the more we select certain suggestions or click certain links, the more likely that suggestions and links like them will be presented to us. Those predictions are responding to the data gathered from our own activity and triangulating it with the data gathered from millions of others, using the aggregate to guess what we want or want to do next. This predictive capability is what powers technologies as apparently diverse as language translation apps, self-driving cars, and personal assistants like Alexa and Siri, as well as programs that make less immediately tangible suggestions and predictions, like weather forecasting, stock sales, and shipping routes.

AI Is All Around Us

AI is a defining technology of our time, given its rapid proliferation in the last few decades. As individuals, we engage with AI in myriad of ways, sometimes directly and other times indirectly, and often it is used and administered without our knowledge or consent. Our interaction with AI goes well beyond the facial recognition software used to log into the newest smartphones. Increasingly, cities and states are using AI-powered tools to track, monitor, and surveil citizens to achieve a range of goals and policy objectives, such as monitoring traffic congestion, evaluating potential child neglect and abuse cases for risk of child death and/or injury, and analyzing DNA samples to determine the probability that a sample is from a potential suspect. On February 11, 2019, President Trump issued an executive order on “Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence,” prioritizing AI development.

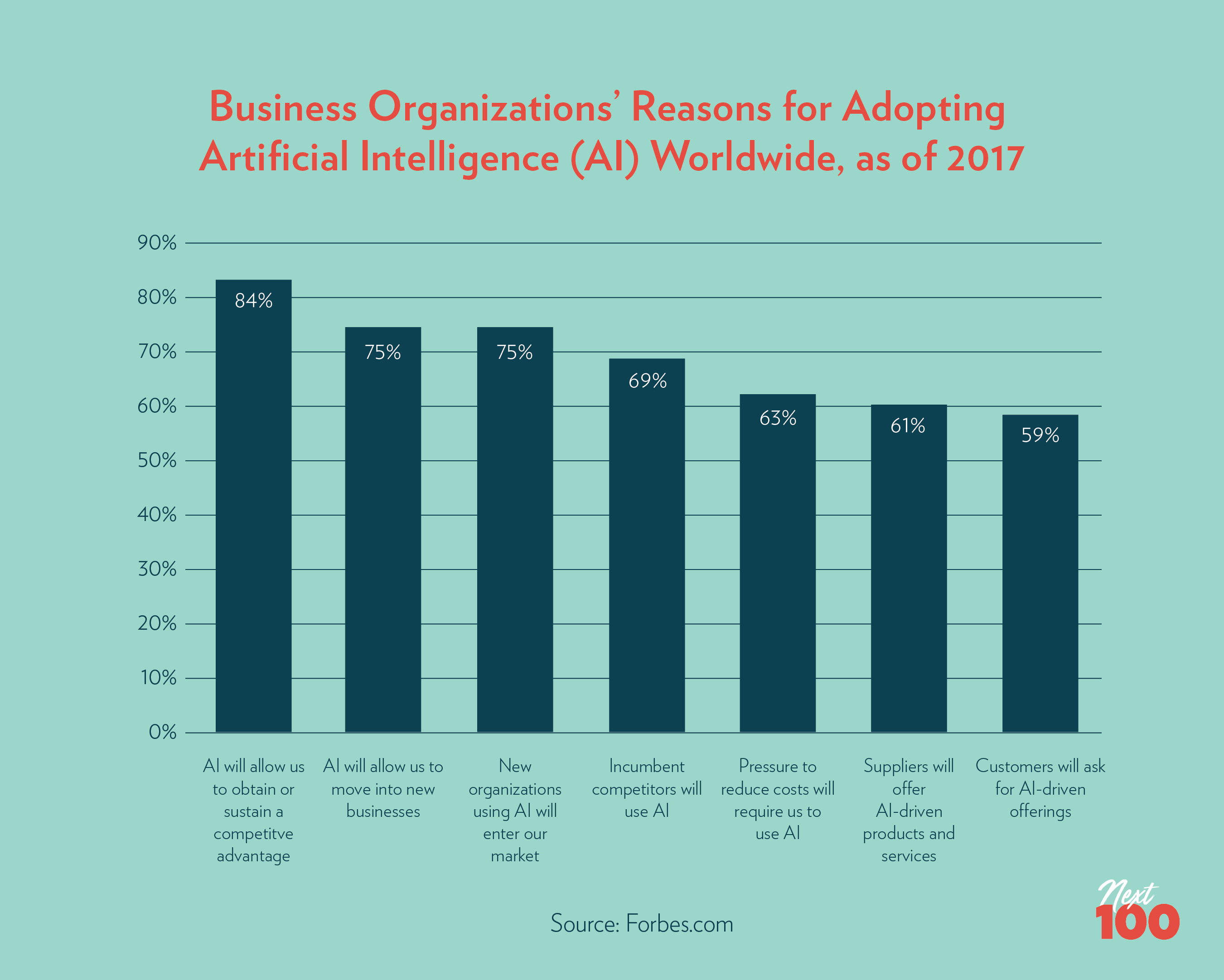

The private sector is investing in the technology just as heavily. Businesses are using AI to improve their analytical and strategic capabilities to drive hiring and management practices and decisions. Algorithmic management—the use of massive datasets (or “Big Data”), artificial intelligence systems, and algorithms to replace, manage, and surveil workforces—has become more widespread in companies across all sectors of the economy. Some of the increase in worker activism we’ve seen as of late, and especially in the tech sector, has been in large part due to the growing prominence of algorithms that track, score, and rank almost everything workers do, and many are choosing to speak out against the unethical use of AI by their employers.

In essence, many of the decisions we make—and those being made for us—are being influenced by AI. As AI has become more embedded in our lives, many watchdog and advocacy organizations, policymakers, and the broader public are beginning to question and challenge the lawfulness and ethics of the technology, its impact (negative and positive), and consequences (intended and unintended).

A Machine May Be Vetting You in Your Next Job Interview

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to record U.S. unemployment claims, while also spurring new hiring demands in some sectors. In fact, companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook have decided to move to online job interviews, for at least the duration of the outbreak. However, for years, long before the COVID-19 outbreak, job applicants have been subjected to AI in the recruitment and hiring processes when applying for jobs online. If you have submitted an application online, you probably have, too. Companies, small and large, have been using AI in hopes of bringing more objectivity and efficiency to hiring and recruitment (e.g. scanning and screening resumes and cover letters and scheduling interviews). Some AI screening software systems used by businesses can eliminate more than 70 percent of job applicants without any human interaction.

For years, job applicants have been subjected to AI in the recruitment and hiring processes when applying for jobs online. If you have submitted an application online, you probably have, too. Companies, small and large, have been using AI in hopes of bringing more objectivity and efficiency to hiring and recruitment (e.g. scanning and screening resumes and cover letters and scheduling interviews). Some AI screening software systems used by businesses can eliminate more than 70 percent of job applicants without any human interaction.

Increasingly, AI is also being used in video interviews to better assess a candidate’s qualities, such as confidence, skills, and experience. The AI is built on algorithms that assess applicants against a database of tens of thousands of pieces of facial and linguistic information. These are compiled from previous interviews of “successful hires,” or those who have gone on to be successful at the job. Although these AI interviewing technologies vary in terms of their design, generally they work like this: Companies give pre-determined questions to job candidates, which the candidate then answers via camera through a laptop or smartphone. AI software then analyzes these videos, evaluating the candidate’s facial expressions, their use of passive or active body language, and vocal tone, as well as other data points, which are then translated into a score. For example, the software may analyze applicants’ facial features, such as smiling, brow raising or furrowing, and emotional states, such as when they react to the mention of the company’s brand. The software then provides employers with feedback that is used to evaluate whether to hire the candidate. This move towards AI interviewing comes as greater numbers of companies are outsourcing work to third-party companies like HireVue to help them wade through oceans of video interviews.

The Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act

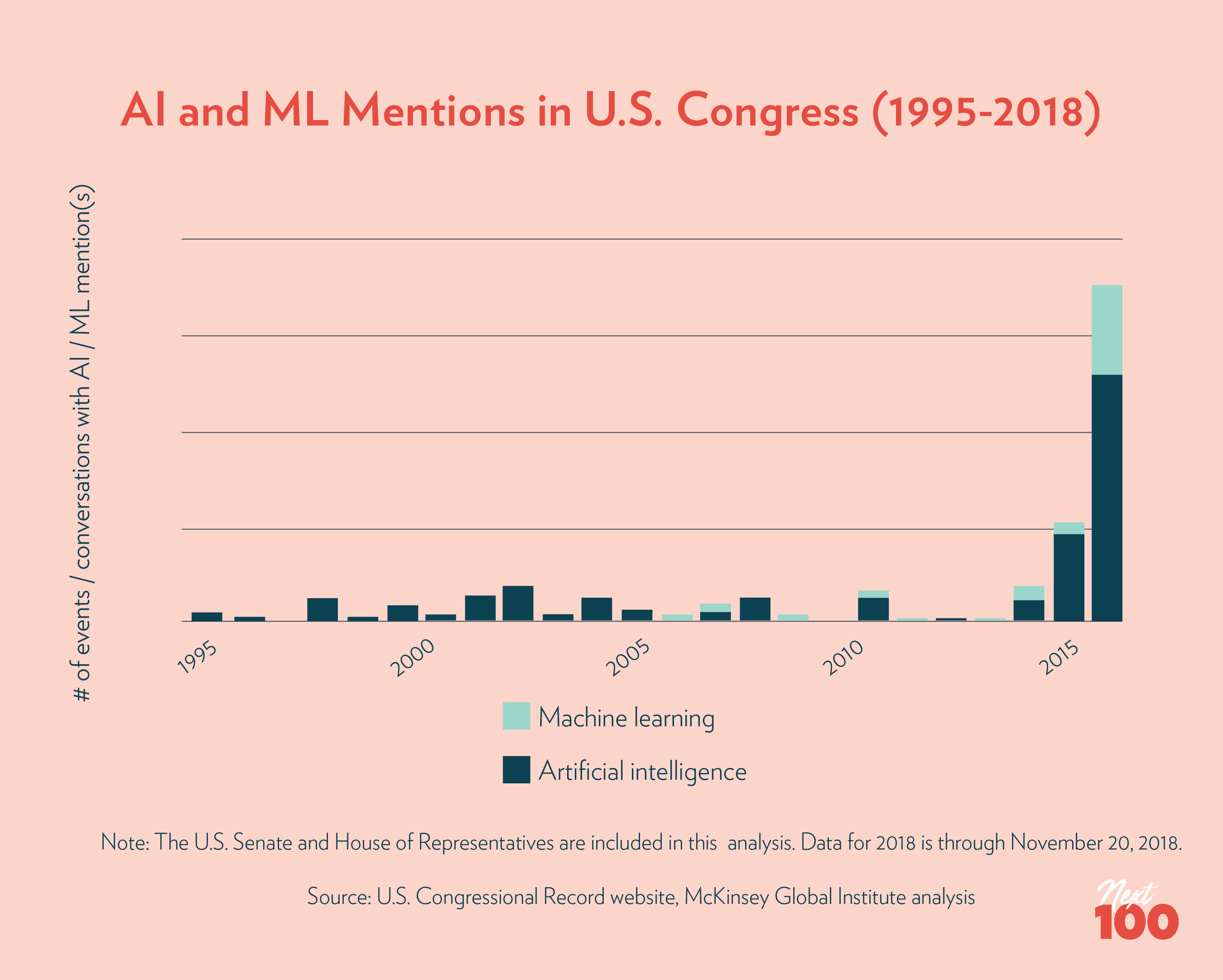

Over the last decade, the government’s attention on the topic of AI technology and its impact on the public has been relatively slow. But in recent years, there are signs that this could be changing, as a number of city, state, and federal proposals have been proposed or enacted in the areas of AI regulation. Illinois’s Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act (AIVIA) is part of that turn.

figure 2

Members of Congress have introduced several resolutions and bills shaping U.S. policy on artificial intelligence. As of now, Congress has passed one, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence Act, which established the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, a group that Congress tasked with researching ways “to advance the development of AI for national security and defense purposes.” On April 10, 2019, congressional Democrats introduced the Algorithmic Accountability Act (AAA) of 2019, aimed at improving federal oversight of AI and data privacy. (In some ways, the proposed law is similar to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.) If passed, the AAA would regulate AI systems as well as any “automated decision system” (ASD) making a decision or facilitating human decision-making that impacts users, and push companies to check and audit their algorithms for bias. And effective January 1 of this year, California’s sweeping data privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act, has gone into effect. Keep in mind, though, that for the first year the scope of the law only covers consumers, leaving open questions about the law’s impact on, and implications for, workers and workplaces. And last May, San Francisco passed a ban on the use of facial recognition software by police and other government agencies.

Finally, on January 1, 2020, as we rang in the new year and the new decade, the Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act (AIVIA), a.k.a. “Illinois-HB 2557,” took effect in Illinois. With this law, Illinois became the first state (although others are looking to follow) to address the growing prevalence of companies’ use of artificial intelligence in employment practices, specifically the use of AI in hiring decisions. Generally, AIVIA’s solution is not to limit the use of AI in these situations, but to grant certain rights to prospective job applicants.

The AIVIA joins this cohort of AI policies, but has the distinction of focusing specifically on labor and workers, creating new rights for workers in terms of how AI is used in hiring processes.

The AIVIA joins this cohort of AI policies, but has the distinction of focusing specifically on labor and workers, creating new rights for workers in terms of how AI is used in hiring processes. Under this law, Illinois employers will not be able to use artificial intelligence to analyze and evaluate a job applicant’s video interviews unless the employer:

- notifies the applicant in writing before the interview;

- explains how the artificial intelligence works and the characteristics that will used by the artificial intelligence program to evaluate the applicant; and

- obtains the applicant’s consent to be evaluated by the artificial intelligence program.

Furthermore, the bill states that employers cannot use artificial intelligence to evaluate applicants who do not consent to artificial intelligence analysis, and that video interviews must be kept confidential. Employers cannot share applicant videos with anyone other than those “whose expertise is necessary in order to evaluate an applicant’s fitness for a position.” Videos—along with any existing copies—must be destroyed within thirty days after request by an applicant.

Will the AIVIA Work?

As the first of its kind, this bill is an important step in addressing the issues of transparency, consent, and notification surrounding the use of AI technologies. Its goal is clear: Employers may continue to use these AI programs, as long as applicants consent and understand the program; and as long as videos are used only for the purpose of hiring. It ensures that interviews are kept confidential and not shared with those who are not necessary for evaluating the applicant’s fitness for the position.

And yet, it remains to be seen what the bill’s effects will be on employers and applicants. Only implementation will tell.

However, we may already be able to identify potential limitations, around the notifications required for applicants, the implications of an applicant’s decision to opt out of the video process, and lack of clarity around key terms. As some have noted, the bill’s language is not clear on what is considered an adequate “explanation” of the AI being used, which employers must provide to applicants. How much detail is required? Today, there are countless ways that we must provide legal “consent” before doing all sorts of things, from starting a new job, to buying a new cell phone or receiving medical care, binding us in all sorts of legal arrangements; but often the language is unclear, complicated, and difficult to understand even for someone with a legal background, let alone a layperson.

In addition, the law does not define what it means by “artificial intelligence.” Currently, there is no consistent, agreed-upon definition, and as noted above, AI is a broad term: its meaning may vary based on its use, purpose, and application.

Critically, the legislation is not clear as to what will happen if applicants refuse to give consent. Will they be interviewed by an employer’s representative, or would they not be considered as an applicant? It is important that measures are in place to ensure that applicants are not adversely or systematically disadvantaged if they choose not to give consent, which would defeat a core purpose of the legislation.

Finally, although the law aims to give greater transparency to job applicants about their exposure to AI technology, it does not address the potential equity problems and risks that could result from outsourcing job interviews to AI. These concerns are important to consider as companies increase and expand their use of AI and as we engage in the broader context, conversations, and controversies around AI and workers.

Indeed, AI has proven to speed up hiring processes, lower production and service costs, and impose standards to ensure better quality and fewer errors. However, some AI has also proven to be biased and discriminatory and, as some argue, serves to reinforce existing stereotypes and inequalities. In fact, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), concerned about these issues, is evaluating employment discrimination protections and how they can apply to the context of AI-powered systems. Similarly, the Obama administration issued a report on AI, algorithmic systems, and civil rights issues. On the one hand, the report outlined AI’s potential for positive impact, while on the other hand, it emphasized the challenges that AI presents, notably its “potential of encoding discrimination in automated decisions.”

These equity and rights concerns can be categorized in three ways: the black box problem, bias, and discrimination—none of which Illinois’s AIVIA addresses.

The Black Box Problem

For one, AI systems are prone to what’s called the “black box problem,” which means that, as AI systems’ learning approaches become more complex, the rationale behind their automated decision-making processes become more difficult to pinpoint and understand, even to those who have developed them. The algorithms will do what they are supposed to do—that is, identify patterns and trends and respond accordingly to them. Ultimately though, the reasons for these decisions will not be clear. Therefore, it’s possible, even likely, that a recruiter or hiring manager won’t fully understand why the system chose some candidates over others. Beyond the obvious lack of fairness this creates for candidates, one could imagine that this also potentially opens up companies to liability for not being able to explain their hiring decisions. For example, if a candidate were to claim that a rejection was based on a protected characteristic (e.g. sex, race, or disability), the employer might have a difficult time defending the decision, because there would be no articulated explanation of the full rationale behind their own hiring decisions. Automated decision-making processes can have an enormous impact on shaping the applicant pool; thus, the extent of this impact is something that should be understood by the public. The ability to interrogate an AI system’s administrators about how it reached its conclusions is a fundamental legal right that candidates ought to have.

Bias and Discrimination

In some cases, with the right kind of investment, AI systems can be designed to counteract, or minimize the black box problem. However, even the intention to design software that counteracts its own biases cannot guarantee that bias will not occur. Amazon, for example, after one year, had to scrap an AI recruiting tool they had been using because they found it was biased against female candidates.

This darker side to AI has been well-documented in research and the media. The programs we build to supplement our decision-making and other functions aren’t necessarily immune to our most human biases and antipathies. For instance, Google’s photo-tagging software was found to classify dark-skinned users as “gorillas.” Algorithms used in courtroom sentencing that presumably have “erased” human bias are found to be more lenient to white people than to people of color. The world’s top facial recognition softwares, even those used by national governments and law enforcement agencies, have trouble identifying faces of different races equally successfully. And as discussed above, the intention to counter such biases does not guarantee that biases will be eliminated.

All this points to one crucial fact, one which is still too little-known: human bias is in human data.

Human bias is in human data.

A common fallacy about technology is that it doesn’t require human labor or input to function or operate. So, although we hear (and see) examples of AI machines replacing humans, the reality is that machines and computer programs are still prone to error and bias because (1) AI and algorithmic systems are still designed—and maintained by—human labor, and (2) the data on which algorithms “learn,” which shapes and informs these systems, comes from a world where conscious and unconscious bias exists. Thus, discrimination and adverse impacts inevitably occur. The data on which AI “learns” to judge candidates contains existing sets of beliefs, so if the AI software is fed data of candidates who were successful in the past, companies are more likely to hire the similar profiles of people, from similar backgrounds. Amazon’s resume screening tool discriminated against women, not because the developers who designed the system were sexist, but because the data driving the algorithms was generated from decades of norms and structures rooted in male-dominated cultures, sexism, and lack of diversity. AI’s central purpose (and primary benefit), which is to reason and to learn so as to predict—and at scale—is what makes the inevitability of bias so problematic and dangerous. If an AI system is inherently biased and thus flawed, then its predictions will also be biased and flawed.

Despite its intention to grant rights to job applicants, these potential risks that AI systems pose—the black box problem, possible bias and discrimination—are not currently addressed under Illinois’s AIVIA. And few companies disclose their methods for addressing bias in audits in considerable detail as well as results of audits conducted by third parties. Thus, we will have to keep a pulse on how the law is applied and its success. Other states, especially those that may follow suit with laws of their own, could end up taking AIVIA’s outcomes as encouragement or discouragement. But the growth of AI’s impact on work, for good and ill, is certain; and policymakers need to be prepared to respond.