A Silent Life Sentence

Even as we finally begin to have a national conversation about criminal justice reform, and work to decrease mass incarceration, we are too often ignoring imprisonment’s long-term consequences—in particular, the 44,000 of our laws and policies that stop the formerly incarcerated from productively reentering society.

As we watch the presidential debates, waiting to see who will be the individual who takes over the most powerful seat in the world, we’ve listened to each of the contenders lay out their plans for health care, education, the economy, and, in some cases, criminal justice reform. All of the issues discussed are extremely important, due to the impact each of them has on many Americans; but what has stood out to me the most about the debates has been the discussions about criminal justice reform.

There have been similar conversations around criminal justice reform in the past few years. Films like 13th, When They See Us, and the trials and tribulations of rap artist Meek Mill have done much to direct national attention to the issue. There is now agreement amongst so many politicians, for example, that the 1994 “tough on crime” legislation was a mistake, and that communities of color bore the greatest burden of the damage the legislation has caused. There have also been conversations and some movement in the areas of bail reform, alternatives to incarceration, sentencing reform, and broadly reducing the prison population.

And yet, even as yet another candidate criticizes the 1994 crime bill, and even as we have yet another conversation about decreasing incarceration rates, one issue seems to never rise to the top of the criminal justice reform conversation: collateral consequences. In fact, the issue is so under-discussed that many Americans have no idea what they are.

To summarize, here’s what they are: Perpetual punishment. A silent life sentence. The 44,000 ways we continue to punish formerly incarcerated individuals after they’ve served their time—the 44,000 different ways we continue to take away the rights and opportunities of people after they are released from prison.

We are hearing a lot about the many ways the 1994 crime bill sent too many people to prison. About how it sent the wrong people to prison. About how we need to send fewer people to prison. But we don’t hear nearly as much about what we are going to do for those folks who were incarcerated under that law—and so many other unjust laws—but are now out, facing perpetual punishment for something we regret punishing them for at all.

We need to change the conversation; and we need to change those laws—laws that have made nearly every sentence into a silent life sentence.

We need to change that. We need to change the conversation; and we need to change those laws—laws that have made nearly every sentence into a silent life sentence.

My Story

That’s me. I’m one of those people. Born and raised in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, it was common for people in my community to be in and out of prison. Me and my family were no different. I spent sixteen-plus years of my adolescent and adult years in and out of prison before I decided enough was enough. I began working with young people—which I loved. It brought so much meaning to my life, and gave me a way to help give young people choices and opportunities that I needed, but didn’t have.

Then that all changed.

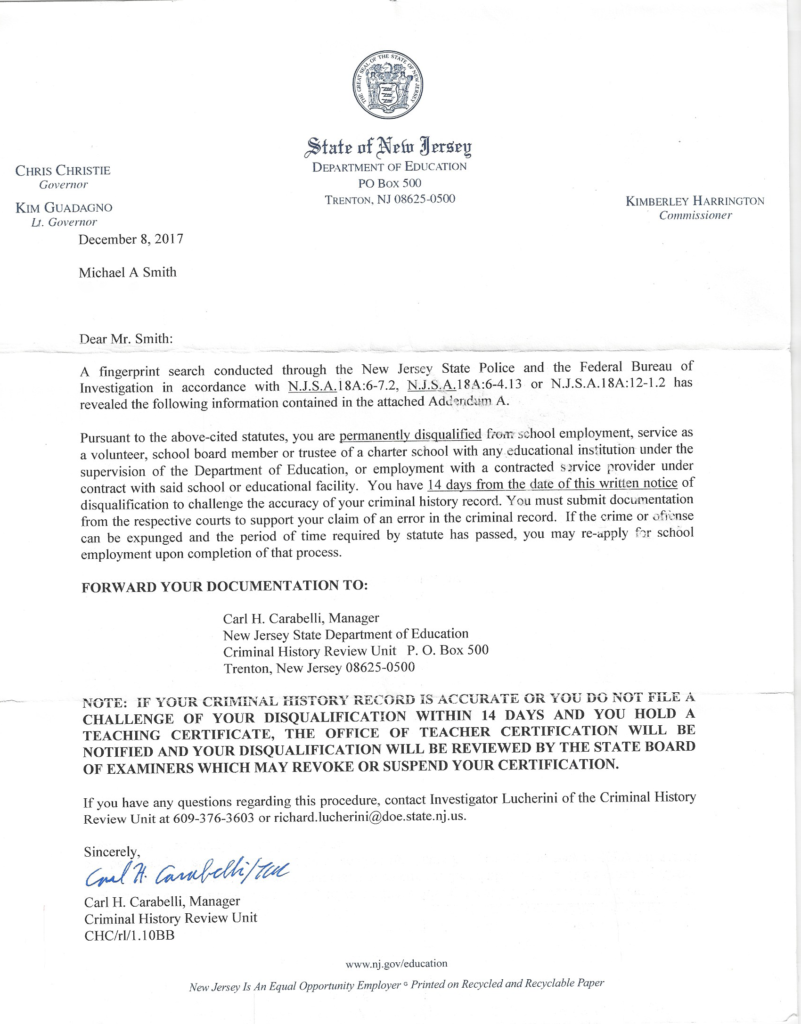

On December 14, 2017, as I got ready to head out for work, I saw a letter that was addressed to me from the fingerprint unit of the New Jersey State Board of Education. I didn’t know that it would change my life.

You see, for the past four and a half years I had been working for a nonprofit organization called The Future Project as a dream director, at East Side High School in Newark, New Jersey. I loved the work: empowering young people, helping to build school spirit and culture, helping to remove disempowering norms, and creating space for young people to pursue their passion and purpose. (And that was after another ten years prior to that spent working with other nonprofit organizations that help to empower young people.) I had an amazing relationship with my principal, staff, and students at the school. I loved my job; and most of all, I loved the students I worked with every day.

But I opened the letter to discover that none of that mattered. The New Jersey State Board of Education said that I could no longer work in any school in the state of New Jersey, due to my criminal history. And that was that. The only option the document left me was to refute the accuracy of my criminal history—which I could not do. There was no option to show who I had been in the world in the fifteen years since my release from prison. No option to demonstrate the ways in which I had contributed powerfully to the lives of countless young people. No option for the school and community I worked with every day to show their support for me and their belief in me. No way to demonstrate the shift in my own personal mindset, the shift in my whole life.

There was no option to show who I had been in the world in the fifteen years since my release from prison. No option to demonstrate the ways in which I had contributed powerfully to the lives of countless young people. No option for the school and community I worked with every day to show their support for me and their belief in me.

Based on that letter, no matter what I had done with my life, I would always be an ex-con and nothing more. I would always be judged according to that.

This truly baffled me. My mind and my soul required me to push further, to try to find a way. I tapped into all of the relationships that I had built in Newark that could possibly give me some advice—and more importantly, some relief. But no. There were no options.

Instead, I came across a term I had never heard before—and as I read, I thought to myself, Why the hell hadn’t I? The term was “collateral consequences.” According to the National Inventory of the Collateral Consequences of Conviction, a resource maintained by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance, collateral consequences are “legal and regulatory restrictions that limit or prohibit people convicted of crimes from accessing employment, business and occupational licensing, housing, voting, education, and other rights, benefits, and opportunities.”

Let me put it to you in plain English: This means that if you are found guilty in a trial, or plead guilty in a plea agreement, you can serve your time—but that time will not be enough. You also automatically receive a silent life sentence of discrimination. You can now legally be denied a job, a place to live, licensing for your job, educational opportunities, the ability to receive public benefits, and, in some states, the ability to vote—for the rest of your life. In some states, some of these permanent consequences are even attached to an arrest, not just a conviction. In these cases, innocent until proven guilty doesn’t apply.

As I read this, I thought to myself: “How did I not know? Why wasn’t I advised of this by my attorney?”

These policies don’t make sense for individuals like me—or for society. They need to be wiped from the books.

The Need to Eliminate Collateral Consequences

Here are three key reasons why collateral consequences are costing not just those convicted, but everyone in the nation.

Collateral consequences increase recidivism. According to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) briefing report, Collateral Consequences: The Crossroads of Punishment, Redemption and the Effects on Communities, “there are over 44,000 collateral consequences laws at the state and federal level, with 60-70 percent of those related to employment.” And we know that on an annual basis, prisons at both the federal and state level release 620,000 individuals back into their communities.

Think about that: 620,000 individuals released every year, with 44,000 distinct legal barriers stop them from successfully reentering society.

With these kinds of barriers, what are the chances of a person successfully returning to society? Can any amount of desire and effort on their part make any difference against such obstacles? Where do they live, if both public and private housing can deny them a roof over their head that they can afford? Where do they work, if employers, large and small, can deny them a job they are ready, willing, and able to do? What are the opportunities for their education, if schools can deny them admission, or financial aid, on the basis of their record? Where’s their fair chance?

Housing, employment, education (not to mention voting)—these barriers would be challenging for anyone. But they are all the more challenging for those who have been released from prison. Many people released from prison are on some form of supervised release. That can be parole or probation—and two of the main conditions for both of these releases are maintaining employment and maintaining housing. A failure to maintain one of these conditions could send you back to prison—even though it could be because of the barriers of collateral consequences.

Without stable employment, housing, and access to education, it is difficult for those who have been incarcerated to successfully reenter their communities as productive citizens. The laws of parole and probation are alleged to encourage the acquisition of those stabilizing life circumstances. But when those same laws meet the laws of collateral consequences—which, in 44,000 different ways, prevent individuals who are leaving prison from acquiring those very parole and probation requirements—a loop is created. In basic legal terms, even successfully completing parole is nearly impossible.

According to the USCCR briefing report on collateral consequences, “Research has shown that unemployment is a major cause of recidivism, and if formerly incarcerated individuals can obtain a job with a living wage that meets their basic needs, the risk of reoffending decreases.” Another study found that the states that had the lowest barriers to obtain occupational licensing saw an average 2.5 percent decline in the recidivism rate, from 9 percent to 6.5 percent.

If the 1994 crime bill further stoked the flames of mass incarceration, collateral consequences made sure that the prisons stay full.

Collateral consequences may make communities less safe. As I understand it, the alleged purpose of many of these collateral consequences, and the perpetual punishment that they create, is to keep communities safe. I understand the desire behind this purpose in specific, targeted cases—the desire to prohibit a person who has been convicted of rape or harm to children to be allowed to run a day care center, for example, or a person who’s been convicted of fraud to be the manager of your local Bank of America.

But people are redeemable, and collateral consequence laws are so much more sweeping than that, so much so that the Wisconsin Law Review says they “bear little or no relationship to the conduct underlying the crime.” What about the person convicted of drug possession (under a sentencing regime we now criticize), but disqualified years later from receiving an electrician’s license, or receiving financial aid to attend college? The reality is that people are being denied access to employment, housing, occupational licensing, education, and voting not because their crimes are related in some way to these areas in which they’re applying, but because we are choosing to forever punish them, even after they have done their time.

In setting up these barriers, collateral consequences jeopardize the ability for the people they affect to meet their own basic needs. And let’s not forget: it doesn’t just affect those who are formerly incarcerated, but those who love and depend on them, too. It jeopardizes the well-being of their families and of their children.

Who’s being protected in that?

Collateral consequences affect far too many people.The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that between 70 million and 100 million adults in the United States have a criminal record of some sort—a felony conviction, a misdemeanor, or an arrest without a conviction. That means that one in every three adults in this country has a criminal record. That’s a lot of human beings and families that have been affected by collateral consequences. That’s a large population of people cast away as second-class citizens. So when I hear this endless debate about criminal justice reform, I can’t help but think about the missing piece: removing the barriers of collateral consequences that will hinder a person’s true success at starting their life over.

Developments in Reform

We are seeing some progress on these issues. States as diverse as Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Utah, and New York have versions of “clean slate” policies that aim to eliminate barriers through record-sealing or expungement for a limited set of eligible individuals. Others, like California and Connecticut, are considering similar efforts. Furthermore, we are seeing groups like Code for America step up to ensure we have the technology to actualize the intents of these laws.

But while incremental steps forward are being made, there is much more that can be done, and specifically in the creation of a distinction about who is “deserving.” In the reforms underway, the option of relief has been limited only to those with low-level misdemeanors and, in some cases, a nonviolent felony offense. This creates the notion that some are redeemable while for others redemption is not possible. It also undermines the mission of doing away with this whole class of unjust laws.

As we move forward with additional initiatives here in New York and elsewhere, I hope we can keep these principles in place:

- No one deserves a lifetime of perpetual punishment after serving their time. Once an individual has served their time, what other debt do we owe? Everyone deserves a fair chance at reintegrating successfully into their life, their community, and their family.

- Relief must be accessible. For relief to be effective, we must broaden the eligibility for who’s getting relief. If we are going to move forward, we must look at everyone that has been impacted by the laws that have been put in place to create this mess in the first place—not limit a fair chance to a narrow set of individuals.

- Relief must be automatic. Individuals who qualify for relief should not have to jump through hoops to access it. For relief to be automatic, it must automatically apply to qualified individuals—and not include layers of paperwork and permission.

- Relief means upgrading technology. For relief to actually be felt, the government must have the infrastructure and technology to actually implement automatic relief—and the funds to upgrade technology as needed.

I have served my time, like millions of others like me. I’m asking for a fair chance.