Formerly Incarcerated People Must Be Included In The Green New Deal

We need intersectional policy solutions that address both climate change and mass incarceration. Creating green jobs for formerly incarcerated people offers the opportunity to do just that.

One of the most widespread misconceptions about climate change is that it’s an isolated “single issue”—that it’s somehow possible to extricate the climate crisis from the other crises we face. I’ve written a bit about this previously, debunking the misconception; and in this piece, I hope to delve deeper into one key intersection: the one between climate change and the crisis of mass incarceration, in particular how climate action can support re-entry for the formerly incarcerated.

There are numerous ways that climate and criminal justice intersect, including toxic waste exposure in prisons, exploitative use of prison labor in response to climate disasters, and more. But a largely underreported intersection is that addressing climate change has the potential to create millions of jobs for formerly incarcerated people. The Green New Deal resolution already proposes creating millions of good, high-wage jobs in the United States. Building on that and focusing on tailoring green jobs to the needs of formerly incarcerated people would ensure that the Green New Deal disproportionately benefits the communities on the front lines of racial and economic exclusion.

But a largely underreported intersection is that addressing climate change has the potential to create millions of jobs for formerly incarcerated people.

Green jobs exist in a variety of sectors and provide numerous benefits. Although “green jobs” are usually perceived strictly as jobs that have to do with environmental management or renewable energy, they can actually exist in a variety of different sectors. In a recent report, “Redefining Green Jobs for a Sustainable Economy,” experts from The Century Foundation and Data for Progress argue that health care workers and educators, for instance, are “green workers” too. The report defines a green job as “any position that is part of the sustainability workforce: a job that contributes to preserving or enhancing the well-being, culture, and governance of both current and future generations, as well as regenerating the natural resources and ecosystems upon which they rely.” This is exactly the sort of inclusive attitude that I want to apply here.

For the past several decades, as mass incarceration has expanded, a new system of systemic socioeconomic exclusion has emerged alongside it, intertwined with it in every way. The harms that these exclusions inflict on the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated, the so-called “collateral consequences” of having undergone time in the system, include tens of thousands of legal barriers formerly incarcerated people face reintegrating into our society and economy—barriers to accessing education, housing, jobs and more. My colleague Zaki Smith has worked extensively to diminish these barriers in an ongoing campaign to #EndPerpetualPunishment. While Zaki works on the crisis from that angle, I’m interested in thinking about how we can use the epic project of decarbonization that we must take on to stop climate change as a way to also systemically empower formerly incarcerated people. Throughout this piece, I will first lay the groundwork for understanding climate change and mass incarceration as two intersecting crises, spotlight a few organizations that are already training and placing formerly incarcerated people in green jobs, and give examples of potential policy responses.

Climate and Criminal Injustice

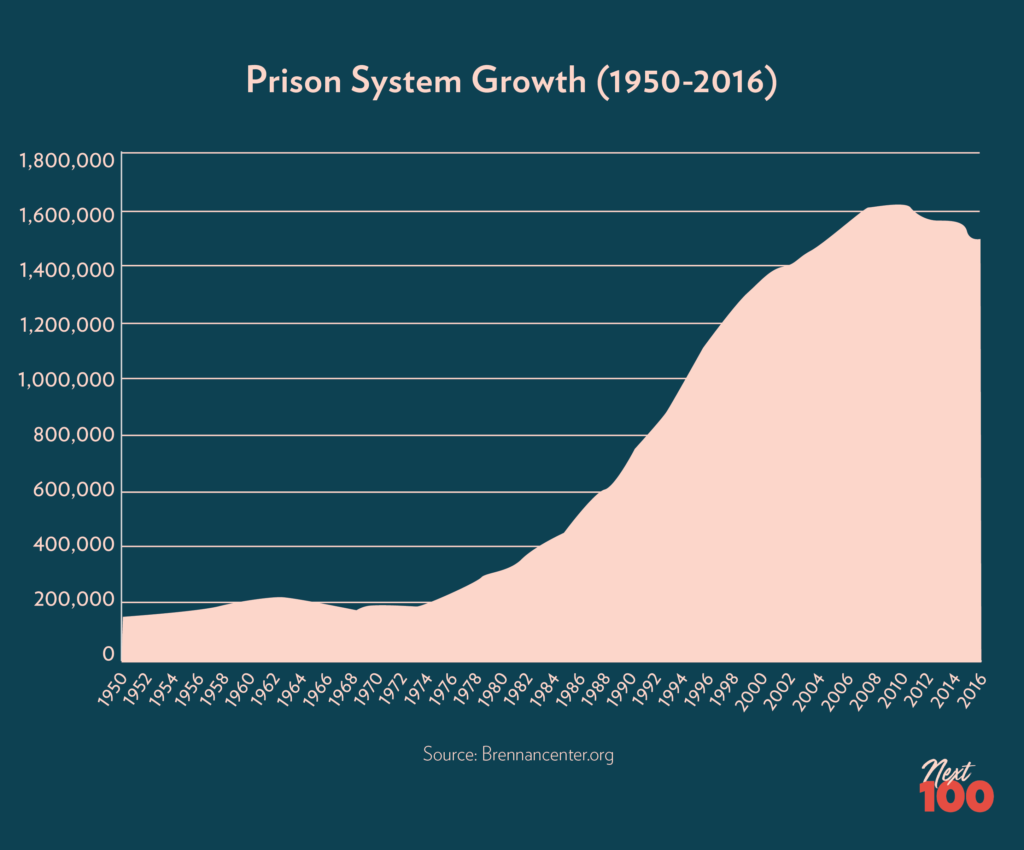

Criminal and climate justice are not usually analyzed in unison. However, tracking these two crises alongside each other highlights a few key similarities. For one, both crises have emerged along similar timelines. Since the 1980s, the amount of people incarcerated in the United States has skyrocketed; meanwhile, since 1970, global CO2 emissions have increased by about 90 percent. Secondly, both phenomena require leadership from the United States, given that we bear a disproportionate responsibility for global greenhouse gas emissions and have the highest incarceration rate in the world. Additionally, both the climate crisis and mass incarceration have had and continue to have devastating implications for racial justice. Our criminal justice system is deeply entrenched with racial bias that disproportionately incarcerates people of color, and the climate crisis also disproportionately affects people of color, exposing them to dangerous levels of pollution and heat.

Meaningful solutions to both challenges intersect as well. Namely, solving both issues involves jobs. Addressing climate change, at scale, will require a ton of work, and has the potential to create millions of jobs. Furthermore, it’s not hard to see how stopping climate change by creating millions of jobs is a winning message, and politicians are catching on. Many of the Democratic candidates for president had green jobs plans—from Senator Warren’s plan to create 10.6 million green jobs to Washington Governor Jay Inslee’s Evergreen Economy Plan, which focused on creating eight million jobs over ten years, and Senator Sanders’s Green New Deal proposal which aims to create 20 million jobs.

At the same time, millions of formerly incarcerated people across the country are in dire need of work. Research conducted by the Prison Policy Initiative found that the unemployment rate of formerly incarcerated people is 27 percent. This is a higher unemployment rate than the total U.S. population’s unemployment rate at any point in history, including during the Great Depression. And this is not a coincidence: it is because of the systemic barriers we put in place between formerly incarcerated people and socioeconomic success.

People with criminal backgrounds face 47,000 laws and policies barring them from reintegrating into various aspects of society, including housing and jobs. What better way to right these wrongs than by ensuring that formerly incarcerated people are included and centered in the growing green economy?

Green jobs are, by most definitions, good jobs.

Furthermore, green jobs are, by most definitions, good jobs. For instance, jobs in the green economy are more likely to be middle class than their non-green counterparts. Research conducted by Brookings Institution found that the mean hourly wages of green jobs are above the national average. Additionally, while nationally more than 30 percent of workers earn under $15 per hour, only 4 percent of green workers earn under $15 per hour. It’s clear that green jobs are good jobs that benefit and socioeconomically uplift those who have them. Given our country’s history of excluding certain groups of people from economic success, we should be thoughtful about who we invest in and support acquiring green jobs. Creating green jobs programs that specifically support formerly incarcerated people who face tens of thousands of barriers to re-entering society is a key way to ensure that we address climate change in an equitable manner. Thankfully, there are already organizations working on making this happen.

Spotlight: Two Exemplary Organizations

Here are just some of the many organizations already doing the work to support formerly incarcerated people in transitioning to green jobs: identifying and prioritizing formerly incarcerated people for roles, providing the necessary training to help them succeed on the job, and providing job placement support.

The Center for Sustainable Careers

The Center for Sustainable Careers in Baltimore, Maryland, serves as a prime example of how to include formerly incarcerated people in the green economy. The Center’s mission is simple: “make Baltimore’s economy more equitable and sustainable.” In a city like Baltimore, which has been devastated by mass incarceration and is already experiencing the impacts of the climate crisis, the urgency of their mission is clear.

The Center does not have any educational requirements for its services; furthermore, 92 percent of the Center’s students have been incarcerated at some point in their lives. The Center embraces this, recognizing that formerly incarcerated people face unique barriers to employment and need support in more than just acquiring technical skills. The Center provides students with things like bus passes, meals, and individualized case management to help support them overcome the barriers they face. They also help participants get their driver’s licenses reinstated and provide financial support to help trainees buy a vehicle, if needed.

They structure their work in three parts: workforce development, social enterprise, and job quality advancement. First, they offer workforce development and training that provide participants with the hard and soft skills necessary to succeed on the job. The training focuses on five key green career tracks: brownfields remediation, residential energy efficiency, stormwater management, solar installation, and land resource management. Secondly, they emphasize “social enterprise” by modeling inclusive hiring practices and ensuring that all of their students get on-the-job training. Third, they work directly with employers encouraging them to commit to equitable hiring practices. In turn, the Center helps these employers grow their businesses by marketing their companies as socially conscious and directing procurement opportunities to them.

Their model has been extremely successful: 94 percent of graduates secure employment, and 92 percent of those who secured employment retain it for at least two years. Furthermore graduates are placed in jobs with a living wage ($13.00-$17.00 per hour) and opportunities for career advancement.

The HOPE Program

The HOPE Program is doing similar work in New York City. The program describes its mission as “empower[ing] low-income residents of the South Bronx and beyond through job training focused on green construction and building maintenance and through a social enterprise that provides paid employment while making New York City more environmentally sustainable.” Many of their trainees are formerly incarcerated.

Their services combine training, education, industry certifications, wellness, and long-term support with job placement. This comprehensive approach has made their job placement rates very high—77 percent of HOPE graduates secure jobs every year. In 2019, HOPE students and graduates earned $11.1 million in wages. The program has partnerships throughout New York City to help employ and retain program graduates.

The success of the Center for Sustainable Careers and the HOPE Program prove not only that it is possible to include formerly incarcerated people in the green economy, but also that they can thrive in the green economy.

Policies to Advance This Intersection of Climate, Incarceration, and Labor

In order to support more pathways into green jobs for formerly incarcerated individuals, there are a number of key policies the federal government, states and local government can put in place. Such policies can be part of federal, state or local level Green New Deal legislation (or through other legislative or regulatory policy vehicles). Here are some that they ought to consider:

- Federal, state, and local governments could support Climate Corps programs, as a part of or modeled after AmeriCorps, that prioritize hiring formerly incarcerated individuals into full-time green jobs that put them on a pathway to green careers. Similarly to AmeriCorps, such programs could bring individuals into climate and environment oriented service roles while paying them a living stipend, offering educational awards and helping prepare them for their next steps. (If you want to learn more about AmeriCorps, see this piece from my Next100 colleagues.)

- Federal, state, and local governments can provide direct criminal justice reentry grants, climate justice grants, or job training grants to organizations like the Center for Sustainable Careers and the HOPE Program that focus on transitioning and supporting formerly incarcerated people into green careers.

- State governments can offer tax credits to businesses for every green job created by a business that hires formerly incarcerated people and keeps them employed for a certain time frame (e.g., at least one year).

- The federal government could ban hiring discrimination on the basis of a criminal record, which would ensure employers of green jobs—and all jobs—do not unfairly discriminate against these individuals. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia have taken the lead on this by implementing “ban the box” laws that prohibit hiring discrimination based on criminal records.

- The U.S. Department of Justice could enact guidelines that ensure conditions of parole and probation don’t interfere with employment, such as weekly in-person reporting during work hours.

- Federal government, state, and local governments could significantly broaden expungement of criminal records, so that they cannot be used in hiring or other decisions, and make such processes automatic. (The Clean Slate initiative has worked on this in New York and elsewhere; see my colleague Zaki’s testimony on this for the New York State Assembly.)

- Federal, state, and local governments could expand their investments in clean energy and energy efficiency, and dedicate a percentage of the funds to workforce development for formerly incarcerated people.

- Federal government, state, and local governments could require businesses that benefit from public investment in clean energy to meet standards around hiring and promoting formerly incarcerated individuals.

Two Crucial Issues That Can Be Addressed Together

The urgency with which we must address the crises of mass incarceration and climate change is clear. At the same time that the planet is spiraling toward ecological collapse, millions of formerly incarcerated people are being barred from economic opportunities all across the country. At every opportunity, we must advance intersectional solutions to the pressing problems we face. We must match the scale of these crises by proposing policy solutions, like the Green Neal Deal, that can address both climate change and mass incarceration. Creating green jobs for formerly incarcerated people offers the opportunity to do just that.