How to Advance Statewide Climate Change Education

Through three case studies of state and local policy models, kier blake presents the most effective methods for developing and implementing a sustainable, equitable, and transformative statewide climate change education program.

Foreword

By William H. Rodick, PhD, P–12 Practice Lead at EdTrust

Environmental justice is educational justice. The students most burdened by environmental harm—those living in fenceline communities, those in neighborhoods lacking mitigation from climate disasters, and those with limited access to stable and affordable housing, quality food options, and safe third spaces— are also the students least likely to attend well-resourced schools. They experience the consequences of environmental injustice every day, yet they may never see those connections reflected in their learning.

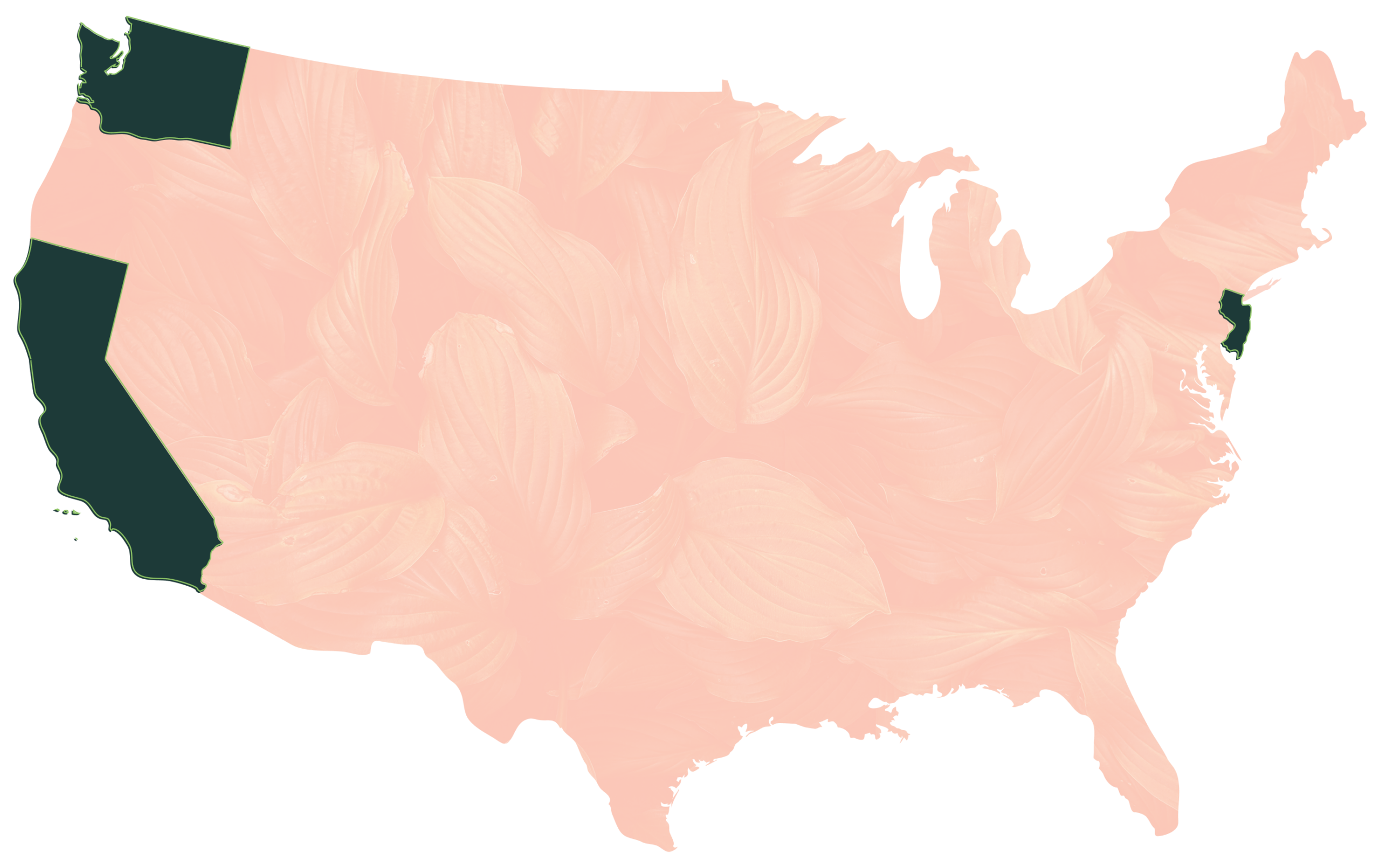

This report shows state advocates how to address this disconnect. Embedding environmental and educational justice into K–12 systems is possible. There are concrete, actionable policy choices that states can make today. Drawing on case studies of policy approaches in California, Washington, and New Jersey, this report shows how collaboration across sectors can turn a policy vision into a stable climate education infrastructure.

The approaches highlighted in this report consistently recognize that students and communities are the experts on the environmental issues they aim to address; place-based learning is essential for building environmental knowledge; and climate education is a tool for addressing injustice and must be firmly rooted in principles of justice and equity.

Importantly, teachers are crucial partners in environmental justice work, not merely implementers of policy. They play a vital role in helping students explore their curiosity, often in contexts where such curiosity, particularly regarding climate change, is considered taboo. Teachers who wish to teach environmental justice are frequently silenced, either directly by censorship laws or indirectly when environmental issues are viewed as supplementary subjects rather than topics deserving their own focus.

Meaningful policy change must recognize this reality. Washington’s ClimeTime model prioritized sustained funding for professional development and built regional intermediaries that allowed teachers to engage with peers and deepen their practice. New Jersey created an entire office devoted to climate education and wove climate standards into every subject area, signaling to teachers that this focus is essential and not optional. California showed how partnerships between nonprofits, higher education, and state systems can produce curricula and support that are both rigorous and locally rooted.

The three cases in this report are explorations of policy, while also emphasizing key lessons for state advocates about implementation. This report illustrates that systemic climate education requires the integration of environmental education standards across subjects and the allocation of dedicated state funding. It shows how regional education entities can bridge state policy and classroom practices, providing teachers the support they need to feel confident in their instruction.

This report provides a roadmap. The question now is how quickly we can build the political will to invest in it—and in the teachers who will bring it to life.

Executive Summary

By embedding climate literacy across standards, establishing guiding committees, empowering regional intermediaries, partnering with universities, ensuring justice-centered design, and—most importantly—securing sustained funding, states can create a durable, systemic approach to climate education. The approach recommended in this report, along with strong implementation, will get us that much closer to ensuring that all students, regardless of geography or background, gain the knowledge, skills, and agency to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

Policy activity in California, Washington, and New Jersey each offer critical lessons on how state-led climate education can move from vision to durable infrastructure:

- Washington shows how network-building, through ClimeTime’s collaboration with grantee stakeholders, educational service districts (ESDs), and the University of Washington’s Institute for Science + Math Education, can create a coordinated process to access high-quality professional learning while embedding equity and Indigenous leadership.

- New Jersey’s Climate Change Education Unit, meanwhile, sets the national benchmark for policy coherence, having integrated climate change across seven content areas and established sustained appropriations to support implementation.

- San Mateo County and Ten Strands in California demonstrate the power of conceptual clarity when held in the hands of non-governmental entities coupling policy passage with implementation strategy, anchoring its Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs) and Blueprint for Environmental Literacy in long-term strategy and cross-sector partnerships.

Together, these experiences point toward some key principles for statewide implementation:

- Embed climate literacy across all standards, following the Climate Change Education Unit’s model of interdisciplinary integration while drawing on San Mateo and Ten Strands’ conceptual tools.

- Establish state-level implementation committees to ensure coherence, accountability, and shared ownership across agencies, LEAs, and Tribal Nations.

- Empower regional education intermediaries—like ESDs and LEAs—to tailor curricula and training to local needs while maintaining equity through state oversight.

- Invest in higher education partnerships so universities anchor professional development in research, pedagogy, and justice-centered practice.

- Secure sustained state funding to move beyond pilots toward systemic integration.

- Embed justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) principles so climate education reflects lived realities and centers historically marginalized communities.

As every state case demonstrates, success is fragile without permanence. Both ClimeTime and California’s ECCLPs have suffered setbacks or roadblocks when budget cycles shifted or philanthropic interest waned, and even New Jersey’s progress depends on political continuity. These realities demand a dual strategy: advancing visible, well-funded programs and building organizing power among teachers, districts, and communities to make climate education implementation permanent. The next frontier is not only to legislate but to institutionalize—to build the local leadership, professional networks, and curriculum ecosystems that make rollback impossible.

Philanthropy can catalyze innovation, but only public investment can guarantee continuity. Dedicated, recurring budget lines within state education agencies—paired with transparent reporting and braided federal support—are what will anchor climate education as a permanent, non-negotiable part of K–12 learning.

The task ahead is to make climate education systemic, equitable, and enduring: a public good too deeply rooted in community partnerships, too effective in classrooms, and too essential to our collective future to ever be dismantled.

Introduction

The climate crisis is no longer a distant threat. It is actively reshaping communities, economies, and daily life in the here and now. Youth especially are on the frontlines of this reality. Globally, young people are grappling with climate anxiety, according to a 2021 Lancet study, and in 2024, 242 million students across eighty-five countries experienced disruptions to their schooling due to “extreme climate events.” This includes the United States, where wildfires, heat waves, and flooding now routinely shut down schools and damage local economies.

These impacts fall heaviest on low-income communities and communities of color, who are experiencing disproportionate environmental burdens across states, localities (urban and rural), and income levels, all while economic development subsidies within the United States continue to transfer public funds to the wealthiest of individuals. For policymakers, this translates into higher public costs—emergency relief spending, infrastructure repairs, lost tax revenue from displaced families, and health impacts from pollution and heat exposure. For example, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) generates roughly $3.2 billion in premium revenue annually and was generally borrowing no more than $1.5 billion, but since before 2005 has had to borrow significantly more each year, notably borrowing $18 billion in 2005 (predominantly Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma), $6 billion in 2012 (Superstorm Sandy), and $10.5 billion (Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria).

But there’s more at stake than immediate damage. The next generation—and our future workforce—will inherit the consequences of today’s policy choices. Without robust, justice-centered climate education, students will enter adulthood unprepared to navigate or mitigate the climate disruptions that will define their lives and livelihoods. States that fail to invest in climate literacy risk a skills gap that undermines both economic competitiveness and community resilience.

But meaningful climate education is not only possible: it’s already happening in some places here in the United States. These initiatives show that state-level leadership can equip students and educators with the tools to innovate solutions, strengthen local resilience, and build equitable futures.

The cost of inaction is staggering; at the same time, the reward for preparation is an investment in stability, justice, and prosperity. Policymakers who embed climate literacy in state education systems are not just preparing students for a changing planet—they are protecting the health, economy, and democratic resilience of their constituents.

Why Critical Climate Education Should Be Part of the Response

When policymakers are looking for robust, systemic responses to the climate crisis, one of the most powerful levers is critical climate change education (CCCE). This approach to teaching climate change doesn’t just teach science: it also teaches how climate, justice, systems, policy, and community intersect. As such, it aligns directly with what good policymaking itself seeks to offer: integrated, holistic solutions.

Here are the key reasons policymakers should anchor CCCE in their climate-education strategies:

1. Systems thinking and cross-sector integration for action: CCCE goes beyond “here’s the science of greenhouse gases” to help students understand how local environmental issues link to global systems of power, economy, and injustice. As I explained in an earlier piece for Next100, it “focuses on the intersections of environmental issues with various axes of oppression and justice, offering a holistic and transformative approach to learning.” CCCE goes beyond knowledge transmission, building skills, agency, and action. For policymakers, this means CCCE helps build a constituency—future workers, voters, community leaders—who are equipped to think across silos: environment, education, economic development, social equity. That makes CCCE a tool for integrated policy implementation, not just a standalone curriculum. From an education policymaker’s lens, that means that not only is content being disseminated: it’s also being absorbed with the intent to act.

2.Equity and justice-centered outcomes based around a holistic approach: CCCE explicitly embeds culturally relevant pedagogy, social-emotional learning, and civic readiness in the following ways:

2.Equity and justice-centered outcomes based around a holistic approach: CCCE explicitly embeds culturally relevant pedagogy, social-emotional learning, and civic readiness in the following ways:

- It centers culturally relevant education (CRE) so that curricula connect with students’ lived experiences, especially those from historically marginalized communities.

- It uses social-emotional learning (SEL) so that students can process climate anxiety, build resilience, and turn their concerns into agency.

- And, finally, it cultivates civic readiness so that learners not only understand policy issues but can engage with them—for example, “Students could engage with local environmental activists, and later conduct a mock city council meeting to debate a proposed bill on reducing plastic use.”

For policymakers, this means CCCE is not an add-on—it is aligned with deeper goals of equity, social mobility, civic engagement, and making sure all communities—not just affluent ones—can participate in climate solutions.

3.Promotes community-rooted and place-based action that enables interdisciplinary integration: CCCE encourages local investigation of issues (such as food deserts, neighborhood pollution, and access to green space) and connects them to larger climate systems. For policy design, that means the education system becomes a bridge between state policy and local community conditions. Students become part of the feedback loop: they observe local realities, connect to broader policies, and can become agents of change locally. That is precisely the kind of vertical alignment that good policy seeks. Furthermore, CCCE can be integrated into current standards-based frameworks across subjects (ELA, math, science, social studies), making it a strategic way to embed climate literacy rather than treat it as a separate silo.

Why State-Level Policy Is the Most Effective Approach

Relying solely on local governments, teachers, or nonprofit partners to carry the burden of climate change education perpetuates inequality. We cannot rely on the passion or privilege of a few school educators to prepare our youth for a rapidly changing world. Without state-level commitment, climate education will remain a lottery of access.

State leadership provides the soil in which climate education can thrive and blossom. When states act—embedding climate literacy into standards, funding streams, and accountability mechanics—they guarantee every child access to the knowledge and skills needed to navigate and shape a climate-impacted world.

The Case Studies: Which States Were Selected, and Why

This report draws from the experiences of California, Washington, and New Jersey—three states that have implemented some type of climate education policy at scale—to identify what works, where gaps remain, and how future state policy can build on lessons learned. While some examples from the case studies are no longer extant or are less than state-wide in scope, the analysis in this report demonstrates the ways in which they can still provide excellent models for sustainable state-wide programming.

The workforce of tomorrow demands skills rooted in resilience, justice, and the public good. Yet, climate change education in the United States remains fragmented, underfunded, and vulnerable to political shifts. On one hand, you can have the Texas State Board of Education altering school guidance to direct science textbooks to highlight the benefits of fossil fuels and contextualizing climate change as a “contested theory,” all while New Jersey integrates climate education across all nine K–12 content areas, invests in an Office of Climate Change Education, launches a statewide Climate Education Hub with partners, and creates four regional Climate Change Learning Collaboratives at higher education institutions.

This report shines a light on efforts that highlight key pillars of effective practice with embedding climate change into state learning standards across disciplines, convening state-level implementation committees, leveraging regional education intermediaries, cultivating university partnerships for professional development, and prioritizing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

What You Will Find in This Report

Washington Case Study: This section examines how Washington’s ClimeTime initiative became the nation’s first state-funded K–12 climate education program, showing how legislative leadership, regional networks, and community partnerships built scalable, equity-centered teacher capacity. Readers will learn how Washington’s model embedded professional learning, Indigenous knowledge, and open educational resources into state systems—yielding national lessons on state-level investment in climate education.

New Jersey Case Study: This section details how New Jersey became the first state to embed climate change education across seven K–12 subject areas, establishing a statewide system led by the Department of Education’s Climate Change Education Unit. Readers will learn how the state’s standards, grants, and regional learning collaboratives built an equity-driven, place-based model that links policy, teacher support, and community engagement to make climate literacy universal and locally relevant.

California Case Study: This section shows how California built a two-decade policy foundation and, through Ten Strands’ partnership with San Mateo County Office of Education, created Seeds to Solutions—free, standards-aligned K–12 climate/EJ curriculum backed by professional learning and local implementation. Readers will learn how nonprofit–state collaboration can scale place-based climate literacy, and why durable funding beyond one-time appropriations is essential to sustain and expand impact statewide.

Each case study closes with an overview of the high-level takeaways from that study, outlining the impact details of interest to policymakers. After the case studies, a comparative summary section highlights the key similarities and differences between the subjects of the case studies.

Policy Recommendations: This section provides a comparative snapshot of the policies analyzed in the Washington, New Jersey, and California case studies, highlighting how each weaves together policy, funding, and local implementation to advance equity-centered climate literacy. Readers will also find six policy recommendations outlining how states can replicate these successes—embedding interdisciplinary standards, building implementation committees, funding teacher training, securing durable public investment, and centering justice across all education systems.

Case Study: Washington State and ClimeTime

Washington State has established itself as a pioneer, not only for being the first state to dedicate sustained funding to K–12 climate science education, but also for developing a model that bridges equity, community engagement, and teacher capacity-building.

Sparked by advocacy from Educators for Environment, Equity, and Economy (E3 WA) and supported by Governor Jay Inslee and the legislature, the 2018 launch of ClimeTime through SB 6032 created the nation’s first state-funded climate education grant program. This initiative quickly evolved into a collaborative network involving the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), the University of Washington’s Institute for Science + Math Education (UW-ISME), all nine educational service districts (ESDs) serving 295 school districts, several Tribal schools, and community-based nonprofits. Together, these partners advanced a decentralized, but coordinated system that ensured statewide coherence while allowing for deep local adaptation. Washington’s early investments, paired with intentional design choices—such as centering historically underserved students, embedding Indigenous knowledge, and funding both professional learning and curriculum development—positioned the state as a national leader in climate education.

Overview

In the fall of 2017, educators for Environment, Equity, and Economy Washington (E3 WA)—a professional association and affiliate of the North American Association of Environmental Education (NAAEE) working in partnership with communities to build capacity for environmental and sustainability education (ESE) in the state—and other aligned groups presented budget and policy recommendations to then-governor Jay Inslee that integrated climate education with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). NGSS establishes a consistent structure that enables teachers to teach science through interdisciplinary inquiry and real-world problem-solving, centering major concepts that cut across several scientific and engineering disciplines. The legislature’s allocation of $4 million through SB 6032, Section 501, in 2018 created ClimeTime, the nation’s first state-funded K–12 climate education grant program.

ClimeTime funding was awarded to the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) for grantmaking to the state’s nine educational service districts (ESDs) (collectively serving more than 1 million students) with the expectation of training at least one teacher per grade level in every school statewide. Of the millions allocated annually, $1 million was reserved “solely for community based nonprofits to partner with public schools for Next Generation Science Standards” and build local climate education capacity. ESDs and nonprofits submitted plans using parallel criteria and were evaluated twice annually, ensuring feedback rigor, consistency, and accountability from disbursal to implementation. As a result, new project proposals were based on the previous years’ accomplishments, areas for improvement, and new climate education opportunities to explore.

With these funds, ESDs rolled out NGSS-aligned teacher professional development, instructional materials, and student programming, including externships connecting teachers with local science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) partners to translate field learning into classroom tasks. The ESD structure—designed to save costs while expanding access, streamlining oversight, increasing equity, reducing redundancies, and connecting local schools with state and national resources—proved ideal for this decentralized but coordinated rollout. Each region could adapt programs to local needs while also benefitting from shared state-level resources and accountability (linking back to OSPI), creating a place-based system that balanced statewide coherence and local relevance. The approach fosters innovation across diverse communities.

In 2022, Washington extended this leadership by funding the country’s first dedicated climate integration program at a state education agency, embedding climate learning across subject areas. ClimeTime, orchestrated by OSPI in collaboration with the University of Washington’s Institute for Science + Math Education (UW‑ISME), ultimately, received over $24 million to allocate to capacity-building for educators over the course of eight years. The state added $300,000 annually for pre-service teacher learning to “develop open access climate science educational curriculum for use in teacher preparation programs” through the University of Washington as a part of SB 5092, Section 606(24). As such, ClimeTime supported a diverse network of ESDs, Tribal schools, and community-based organizations and served the goal of better supporting teacher training and linking climate science education standards (ClimSciEd) with NGSS.

Unfortunately, in the final 2025–27 state budget, funding for ClimeTime was discontinued. Nevertheless, the network remains active, offering free and paid climate and science professional development, including canvas courses, in-person training, and virtual communities of practice offered through February of 2026. ClimeTime grantees continue to advocate for renewed climate education funding at the state level.

A Closer Look at ClimeTime’s Dedication to Teacher Development

The ClimeTime model reveals how investments in teacher capacity can create scalable infrastructure for education reform on climate. By embedding professional learning, open educational resources, and cross-sector partnerships within a single framework, the state institutionalized climate literacy and positioned educators as catalysts for systemic transformation.

Ellen Ebert, the Washington State director of K–12 science education at the OSPI, encouraged both ESDs and nonprofits to have an active voice in the administration of climate education in the state. A leadership team was formed drawing from OSPI; the Association of Educational Service Districts (AESD), representing the ESDs as a whole; the OSPI Environmental Program, representing nonprofits committed to creating a collective impact model for the state; and the University of Washington’s Institute of Science + Math, who more deeply developed ClimeTime’s lens for understanding climate justice issues in accordance with their network goals and legislative prerogative. UW’s inclusion was instrumental, in that it provided the research basis for the team’s work, gap-filling training on climate education, and grantee support (developing project portraits and writing STEM Teaching Tools representing the collective body of work created).

At the heart of the ClimeTime network and its leadership team was teacher capacity-building, for which professional learning opportunities are designated to not only increase K–12 teacher confidence in teaching climate science but also to provide teacher events such as the OSPI-led Climate Education Summits and assessment/evaluation strategies in-state, as well as reusable resources for adaptation across the state and beyond. The ClimeTime network provided over 37,000 NGSS-aligned professional learning opportunities in climate and science, leading to over 1 million student learning experiences during its six-year existence.

For example, ClimeTime grantees participated in the Washington Hub of National Open Educational Resource (OER) Commons, which created pathways for reusing and/or reworking the provided materials for local usage. The OER hub was created as a project of OSPI’s Open Educational Resources (OER) Project, which is a free, digital library of high-quality, standards-aligned resources for PK–12 created by and for educators. This is an important distinction, as ClimeTime grantees were all required to place any materials created with their grants on the Resource Commons so that the materials could be shared freely. Some additional highlights of the Resource Commons are that the content is continually reviewed to ensure it is developmentally appropriate, culturally appropriate, and falls into twelve “learning collections,” including social-emotional learning (SEL), media literacy and digital citizenship, and career and technical education (CTE), in addition to more traditional school subjects like math, science, and social studies.

By aligning these materials with NGSS, ClimeTime ensures that they remain relevant while deeply connected to Washington’s local contexts in order to create sustainable educational change. Specifically, a defining feature of ClimeTime has been its equity and inclusion focus within its larger localized professional development strategy, embedded as a core priority in its grant funding criteria. These focus areas include “Anti-racism, equity, and inclusion” and “Professional learning and student engagement in historically underserved areas,” including designs for special education, multilingual, rural, Indigenous, and students of color communities historically underserved by science education.

For example, Chief Leschi School, a State Tribal Education Compact school serving mainly Puyallup Tribal members (the school is located on land which belongs to two-thirds of its students) and other North American tribal members (the remaining one-third of students), is one of the many ClimeTime grantees. The school built programming that centers Indigenous leadership and field-based ecological learning, strengthening Tribal sovereignty in climate education. Furthermore, organizational partnerships with the likes of the Lummi Nation, Northwest Indian College (NWIC), University of Washington, and the Salish Sea Research Center through the Teaching for the Climate field-based professional learning project have equipped K–5 educators with the skills to deliver outdoor, experiential, place-based, and NGSS-aligned climate lessons informed by Indigenous perspectives.

Nonprofit partnerships further extend this work, bringing environmental justice and local relevance into classrooms and communities. For example, the Pacific Education Institute created Solutions Oriented Learning Storylines (SOLS), designed to strengthen teachers’ climate science instruction in utilizing Indigenous Ways of Knowing, NGSS standardization, solutions-oriented lens, and inclusive assessment. It also emphasizes centering student voice and using locally relevant applications to elicit student curiosity while also providing high-quality education. For example, PEI’s Asynchronous Food Waste workshop taught sixteen teachers from ten school districts how breweries participating in societal beverage production create significant waste streams. In a different set of activities, students focused on measuring resource use, such as milk production’s associated greenhouse gas emissions, and conducting snack audits to have students self-reflect on what they themselves could do to reduce food waste. Ninety-seven percent of 126 K–12 educators who participated in the workshops reported deepened climate change knowledge, and one-third of the educators received stipends for the delivery of lessons to their students.

Overall, participants gave the trainings exceptionally strong reviews with nearly all respondents (97 percent) agreeing that the training equipped them with the skills to try new approaches in their professional practice. Furthermore, nine in ten participants reported that useful resources were introduced, and 67–82 percent agreed or strongly agreed that the training enhanced their ability to make learning more inclusive for students of color, English learners, and students with disabilities.

As a result, the ClimeTime network’s leadership team’s stewardship revealed the value of sharing expertise and responsibility across partners, building connections across systems, fostering collaboration within a community of practice, and pushing for broader, more equitable access to professional learning for teachers and science opportunities for students. Taken together, these outcomes highlight how ClimeTime has not only expanded teacher capacity and student learning statewide, but also embedded equity, Indigenous knowledge, and feedback loops that highlight what’s important to the community. It also uplifted everyday climate experts and community partnerships into a sustainable model of climate education that other states can look to as a national exemplar.

Key Takeaways

Washington’s ClimeTime initiative demonstrates how significant state-level investments can embed climate education into the fabric of public schooling in ways that are systemic, community-rooted, and locally responsive. ClimeTime’s distinct strength lies in its structured approach to building teacher capacity. By entrusting the OSPI with implementation, the legislature leveraged existing administrative infrastructure—grant oversight, fiscal management, budget analysis, government relations, communications, and more—to deliver professional learning at scale. This enabled the state’s science team to focus creatively on pedagogical design and collaboration anchored by ESDs, Tribal schools, nonprofits, and the University of Washington’s Institute for Science + Math Education, ensuring both statewide coherence and local relevance, making it a national model for climate literacy.

Washington’s ClimeTime initiative demonstrates how significant state-level investments can embed climate education into the fabric of public schooling in ways that are systemic, community-rooted, and locally responsive.

One initial downside of the initiative that was corrected, according to Ellen Ebert, was the effect of the grant structure, which initially seeded competitiveness amongst grantees. “Grantees were not always willing to share their ideas but this competitiveness did not serve the ClimeTime program or our teachers and students very well,” Ellen reflected. As a result, she and the ClimeTime team worked hard to instill a culture of shared learning and cooperation, creating an economy of scale through cooperation and program betterment. In alignment with the programmatic implementation efforts, work was also put in to keep the legislative sponsors and Governor’s Office apprised of the work being accomplished so the work could continue to be well received. As such, Washington State had the state standards inclusive of climate, human impacts, and weather events, groundwork laid down for integration across the K–12 content areas, and the institutional piece all present.

With the continued flow of millions of dollars worth of individual grants which undergirded the tens of thousands of professional learning opportunities, ClimeTime expanded teacher capacity, produced nationally relevant yet locally adaptable resources, and prioritized equity by centering Indigenous knowledge, historically underserved students, and community-based partnerships.

Nevertheless, with all of the insights and progress gained from such a strong state-level initiative, the provisions that fueled ClimeTime were not immune to legislative fiscal gaps, meaning the ClimeTime program, in addition to almost all similar provisions across all content areas, were cut when determining the 2025–27 biennial budget. As such, the loss of funding highlights the urgent need for sustained, diversified funding strategies beyond the legislature. This goes for initiatives not only including ClimeTime but other programs, such as Outdoor Education, which were complementary to the schools, students, and communities the OSPI served as well.

“ClimeTime should be reinstated,” Ellen said, “but other content areas should be named. For example, we had a group of students use AI to analyze satellite images from NOAA and NASA for areas of environmental degradation. They found one such area in their part of the state. It is important for students to see the interconnectedness of what they are learning…so, an integrated approach to climate education beginning in kindergarten and, importantly, including our high school students. Students should understand how they can make a difference. They need to understand economics, impacts to society (good and bad), and all students must be included.”

For other states considering similar pathways, Washington’s experience offers both a blueprint and a warning: robust, sustainable, equity-driven climate education can take root quickly when supported by state leadership, but long-term stability depends on embedding climate literacy into durable funding streams and institutional frameworks that can withstand political and fiscal change, thereby making it so that climate change education can remain secure in its place within PK–12 learning communities.

ClimeTime Case Study Findings at a Glance

Duration: Six years (2019–2024).

Funding: $24 million over eight years (plus $300,000 per year for pre-service teacher learning provided by UW-ISME).

Highlights:

- Built teacher capacity at scale through Next Generation Science Standards-aligned professional learning, incorporating climate science education.

- Funded regional implementation via educational service districts and competitive grants to nonprofits and tribal partners.

- Produced open educational resources and sustains a statewide community of practice.

Measures for Scale and Access:

- State-funded and state-wide.

- Network coverage: nine ESDs serving 295 school districts and ~1 million students; included some Tribal schools and community-based organizations.

Measures for Educator Capacity and Student Impact:

- 37,000+ NGSS-aligned professional learning opportunities delivered.

- Quality and/or efficacy survey results:

- 97 percent of the K–12 educators who participated in the workshops reported deepened climate knowledge.

-

- 97 percent reported useful skill introduction.

-

- 67–82 percent agreed or strongly agreed that training improved inclusivity for students of color, English learners, and students with disabilities.

- Concrete professional development examples: externships with local STEM partners; Pacific Education Institute created solutions-oriented learning storylines (SOLS) workshops (sixteen teachers and ten districts in one module), with lesson delivery stipends for ~1/3 of participating educators.

Results and Impact to Date:

- Tens of thousands of NGSS-aligned professional development touchpoints for the state’s more than 1 million students.

- Strong OER corpus.

- Empowered ESDs to innovate on a regional level.

- Tribal and nonprofit leadership.

- Loss of state funding threatens continuity despite a mature network.

Case Study: New Jersey and the Climate Change Education Unit

New Jersey has distinguished itself by creating the most comprehensive statewide system for climate change education in the country. Anchored by the 2020 integration of climate standards into all seven K–12 subjects and guided by First Lady Tammy Murphy’s vision, the state built a robust ecosystem linking the newly created Department of Education’s Climate Change Education Unit with higher education institutions, nonprofits, and local districts.

This initiative consisted of a collaborative network involving the Climate Change Education Unit at the New Jersey Department of Education; the Climate Change Learning Collaboratives (CCLCs), which were established through climate literacy grant funds; and nonprofit stakeholders. Together, these partners advanced a centralized system that ensured statewide coherence while allowing for deep local adaptation. New Jersey’s continued investment, paired with top-down standards development and funding support for teachers, has created a sustainable infrastructure that empowers educators to teach climate change through locally relevant, justice-centered, and interdisciplinary approaches, thereby positioning the state as a national leader in climate education.

Overview

In June 2020, the New Jersey Board of Education announced that climate change was to be integrated into the New Jersey Student Learning Standards (NJSLS) across every grade level and the seven subject areas before the state board for approval that year (extending beyond science instruction). This landmark achievement was championed by First Lady Tammy Murphy—an environmental advocate inspired by the 2018–2019 Fridays for Future youth movement, parent, and member of The Climate Reality Project board—whose vision for preparing students for the green economy aligned with Governor Phil Murphy’s Energy Master Plan to achieve 100-percent carbon-neutral clean energy by 2050. Her advocacy catalyzed a multiyear standards revision process involving more than 130 educators, the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE), and a broad network of administrators, nonprofits, and higher education partners. Together, they shaped a framework that embeds climate change across subjects from science and social studies to the arts, world languages, and career readiness, ensuring all students encounter climate learning through multidisciplinary lenses.

Although implementation was delayed until the 2022–23 school year due to the pandemic, New Jersey paired its binding standards with robust special appropriations grants that supercharged implementation and continue to sustain and scale climate education. Developed through multistakeholder input from school board members, NJDOE and federal representatives, education associations, nonprofits, universities, and private partners, these initiatives were convened under a shared commitment to equity, local relevance, and community participation. Together, the multistep process provides professional development, technical assistance, instructional resources, and funding that allow districts to adapt climate learning to local contexts while maintaining statewide coherence.

To guide implementation, a statewide Climate Change Education Thought Leader Committee brought together educators, researchers, policymakers, and nonprofit leaders, producing thirty-four recommendations emphasizing equity, local relevance, and professional learning. Their work laid the foundation for a comprehensive infrastructure that extends beyond classrooms—linking students, families, and community partners to sustainability and resilience education. Since FY2023, $14.225 million has been allocated for grants, technical assistance, and professional development across four years, administered through the NJDOE Climate Change Education Unit. This unit manages several climate literacy grant programs—engaging nearly half of the state’s local education agencies (49 percent)—and oversees four regional climate change learning collaboratives (CCLCs). These collaboratives provide free professional learning, educator stipends, and place-based technical support, while leveraging partnerships with nonprofits such as City Green, NJ Audubon, and Raritan Headwaters to anchor instruction in local contexts.

Through this coordinated system of standards, professional learning, and partnerships, New Jersey has institutionalized climate education statewide while maintaining flexibility for district-level adaptation and continued funding support.

A Closer Look at The Climate Change Education Unit’s Dedication to Place-Based Supports

New Jersey’s climate education model demonstrates how investments in place-based programming and community-centered events can transform statewide climate literacy from policy into lived practice. By embedding interdisciplinary standards across most K–12 subjects and supporting them through regional learning collaboratives, grants, and hands-on events, the state has built an ecosystem where local experience, educator leadership, and community participation reinforce one another, creating a vehicle for both systemic reform and civic engagement.

In the lead up to the NJSLS standards revision, First Lady Murphy consulted with more than 130 educators statewide, and also visited schools that had already carried out strong climate education and sustainability practices. The revision process extended beyond these meetings, drawing on input from a wide range of education stakeholders, including teachers, administrators, nonprofit and agency representatives, higher education institutions, and schools from rural, urban, suburban, public, nonpublic, and charter settings. The New Jersey Department of Education further incorporated feedback gathered through regional testimony sessions and written public comments.

In the process, and to help devise a statewide implementation strategy and guide the rollout of the new NJSLS standards, the Climate Change Education Thought Leader Committee was formed and convened. Co-chaired by Randall Solomon, executive director of Sustainable Jersey, and John Henry, senior manager for STEAM and sustainable schools at the New Jersey School Boards Association, the committee brought together school board members, representatives from the New Jersey Department of Education and federal agencies, major education associations, nonprofit environmental groups, higher education institutions, and private sector partners. Using an iterative process, the committee assessed needs, developed recommendations, and sought input from additional experts across multiple fields.

In spring 2021, the group collected survey data and held discussions to better understand priorities for climate education. Committee members were asked to circulate the survey among colleagues with relevant expertise, and several experienced teachers who had already embedded climate change into their classrooms also contributed insights. All feedback was kept anonymous. Whenever possible, the committee’s recommendations were reinforced with national reports and scholarly research from leading education experts.

The outcomes, goals, and guiding principles of the committee can be summarized as aiming to ensure that the state’s public teachers, within five years, are equipped to integrate scientifically accurate climate change education across every grade and subject. As such, the guidance of the committee proposed that climate literacy should extend beyond classrooms to include students, families, facilities staff, administrators, and community partners, fostering schools that support sustainability and economic resilience comprehensively. Furthermore, they proposed that an equity focus that directs resources to the neediest districts and highlights disproportionate impacts on communities of color, immigrants, and low-income families should be established. Finally, guidance calls for locally grounded, place-based approaches and flexible entry points that respect school and teacher autonomy while motivating communities toward solutions. The committee developed thirty-four recommendations based on the following identified needs: professional learning, curricular resources, community-based climate change education, and ways boards of education can support this process.

Though not always included in climate education, their work emphasized preparing teachers to integrate climate education across all subjects, highlighting disproportionate impacts on vulnerable communities and fostering place-based, justice-centered approaches. Not unrelated to the systemic issues affecting communities, the statewide implementation began in the 2022–2023 school year because of COVID-19 pandemic-related delays, pushing the launch back from its original intention of September 2021. The final result was the full integration of climate change across seven of nine K–12 content areas (Career Readiness, Life Literacies and Key Skills; Comprehensive Health and Physical Education; Computer Science and Design Thinking; Science; Social Studies; Visual and Performing Arts; and World Language), ensuring that students would be exposed to climate change in all subjects.

Once the revision process was completed, the New Jersey Department of Education became the container for the Climate Change Education (CCE) Unit, created within the Office of the Assistant Commissioner of Teaching and Learning. The CCE Unit exists as the entity that distributes and oversees the grants and supports their implementation in accordance with the desired goals of statewide climate change education in all public schools. For example, as a part of the fiscal year 2023 budget, $4.5 million was given to a three-month grant program under the Climate Change Education Unit called the Climate Awareness Education: Implementing the NJSLS for Climate Change and was open to all LEAs in New Jersey. And since then, from 2023 through 2026, $14.225 million has been allocated to support standards implementation and sustain and scale climate literacy initiatives through district climate literacy grants. Since 2023, and proposed to continue in the 2025–26 Education budget, $500,000 is allocated to sustain the Climate Change Education Unit in addition to renewing funds for grant disbursal.

Since the grants are competitive, the Climate Change Education Unit has taken a two-pronged approach. First is to support early implementation through teacher professional development and pilot programs. In FY2023, 49 percent of LEAs (322 in total) participated in the initial grant opportunity, with awards ranging from $6,000 to $7,000. Starting in FY2024, grants began to fund model LEA projects that create high-quality interdisciplinary units and student-led resilience initiatives. These districts (thirty-two in total in FY2024), in turn, served as mentors and models for other schools pursuing similar climate education efforts across the state, with awards ranging from approximately $31,000 to $70,000 through the Climate Change Education and Resilience through Interdisciplinary Learning (CCERIL) Grant, in partnership with CCLCs and other collaborators such as municipal governments and community-based organizations. The FY2024 grant expanded climate change education across all grade levels in eighteen of New Jersey’s twenty-one counties, with 25 percent of grantees representing Title I LEAs. In FY2025, the Climate Literacy for Community Resilience (CLCR) grant supports a new cohort of LEAs in developing interdisciplinary climate education units and community resilience projects, and existing 2024 grantees had the opportunity to extend their funding for an additional year to expand their programs.

Second is to fund the CCLCs, which can support individual teachers—even in districts that may not fully embrace climate change education—thereby extending the program’s reach. In their first year (2024), the CCLCs engaged more than 2,000 teachers through workshops and professional learning opportunities. Additionally, the state’s four regional Climate Change Learning Collaboratives (CCLCs) housed at higher education institutions were established to support implementation across all content areas, reflecting whole-school integration. The competitive grant opportunity funding the CCLCs landed them at four higher education entities: Ramapo College, Rutgers–New Brunswick, Monmouth University, and Stockton University.

According to the CCLC Notice Of Grant Opportunity, CCLCs are required to partner with community-based organizations to provide place-based experiential learning opportunities (ELOs) for teachers. The CCLCs are also required to provide teacher stipends for professional development and ELOs that take place outside contractually obligated hours to honor teachers’ time commitment. As such, the CCLCs were integral in getting teachers outside and educating them so that they could better understand their local climate change education contexts, as well as the challenges of climate change in other parts of the state, giving them better teaching insights. The CCLCs were also important in offering New Jersey public schools free access to professional development, educator stipends, technical assistance, hands-on learning experiences, networking resources, and help pursuing external grants and green/blue career pathways to help implement the New Jersey Student Learning Standards on climate change across all subject areas. Schools are encouraged to connect with their regional CCLC and affiliated websites for guidance and support in advancing climate education initiatives. Each CCLC partners with local nonprofits, e.g., City Green, NJ Audubon, Raritan Headwaters, NJ Sea Grant.

Additionally, the NJDOE’s public guidance emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach and provides curated standards by grade band to help districts weave climate learning throughout curricula. Initiatives such as Action for Earth month offer themed weeks and vetted resources (energy/waste audits, heat resilience, school gardens, invasive-species removal) to spur hands-on, community-embedded learning.

Unlike a single, top-down curriculum, New Jersey’s approach combines required standards with robust supports totalling $14.225 million across the four years of the program (2023–2026), state grants to districts, and regional higher education-led collaboratives offering free professional learning and technical assistance.

Key Takeaways

New Jersey’s climate education initiative demonstrates how significant state-level investments can embed climate education into the fabric of public schooling in ways that share a commitment to equity, local relevance, and community participation. Each CCLC operates independently, with oversight from the CCEU at NJDOE, but with wide latitude to implement professional development and technical assistance according to their individual capacities, partnerships, and audiences. This decentralized model can lead to redundancies or uneven implementation across the state, which the CCEU works to address through collaborative meetings and resource sharing at statewide events.

New Jersey’s climate education initiative demonstrates how significant state-level investments can embed climate education into the fabric of public schooling in ways that share a commitment to equity, local relevance, and community participation.

Although the majority of the content areas were covered, two (Math and English Language Arts) have still not received implementation. ELA and Mathematics did not contain explicit climate standards in their 2016 frameworks; and when ELA and Mathematics were presented to the state board in 2023, the Board of Education signaled that it would not pass Math and ELA revisions with CCE content embedded in the performance expectations. This led to the creation of companion guides that were ideated in order to provide teachers with guidance regarding where CCE could be embedded in instruction or taught across disciplines. NJDOE directed districts to integrate them through interdisciplinary units—signaling flexibility for local adaptation. Along a similar vein, the New Jersey Department of Education still has yet to create accountability measures to ensure that all of the standards are being taught in the seven content areas that did receive the climate-oriented standards revisions (Career Readiness, Life Literacies and Key Skills; Comprehensive Health and Physical Education; Computer Science and Design Thinking; Science; Social Studies; Visual and Performing Arts; and World Language).

It is important to note that, while not a part of the state’s strategy, ancillary supports provided by nonprofits such as the SubjectToClimate-powered Climate Change Education Hub (launched June 2022) played a unique role in delivering free teaching materials (teaching resources, lessons/units/activities) and educator support (professional development, teacher guides, climate change explainers, and guidance for school administrators) via an online portal for educators across all subjects and grade levels. Building off of the short-term recommendations of the Climate Change Education Thought Leader Committee, the New Jersey Climate Change Education Initiative (NJCCEI)—a partnership among the College of New Jersey, National Wildlife Federation, New Jersey Audubon, New Jersey School Boards Association, SubjectToClimate, and Sustainable Jersey—was formed. Consequently, supports like the Hub increased educators’ confidence and preparedness to implement the climate change education standards while enhancing access to professional development. By the second survey, 91 percent of Hub users had incorporated climate change content into their curricula at least once.

Thus, New Jersey’s approach to climate change education illustrates how a state can set standards for interdisciplinary climate literacy while simultaneously empowering local and regional educational entities to co-design learning experiences that reflect their own geographies, cultures, and needs. As a result, it is an example of how statewide mandates can be strengthened through distributed support and localized connections to drive systemic change. By embedding climate change across most K–12 content areas, the state set a universal foundation, but it was with the additions of seed grants, the Climate Change Education Hub, and regional learning collaboratives that ensured that flexibility, local relevance, equity, and justice could remain centered and autonomy could be preserved, steering away from a one-size-fits-all approach. Through cross-sector partnerships spanning NJDOE, Sustainable Jersey, NJSBA, higher education institutions, nonprofits, and local districts, New Jersey has scaled professional learning, resource development, and community-based projects. This model shows how a state can move beyond symbolic standards, building an ecosystem where climate literacy is both universally required and locally co-created, preparing students for the realities of a changing climate and the opportunities of a green economy.

Climate Change Education Unit Case Study Findings at a Glance

Duration: Four years (began 2023, funded through 2026)

Funding: $14.225 million

Highlights:

- Developed free, open, standards-aligned curriculum on climate and environmental justice.

- Coordinated state–county–nonprofit partnerships to pilot, vet, and scale materials.

- Actively seeks sustained professional learning and implementation supports to move beyond one-time appropriations.

Funding and Programmatic Measures:

- $14.225 million allocated across FY2023–FY2026 to fund grants, technical assistance, and professional development.

- $4.5 million initial grant program (FY2023), called Climate Awareness Education: Implementing the NJSLS for Climate Change, reached 49 percent of the state’s Local Education Agencies (322 LEAs).

- Sustained $500,000 annual allocation to the Climate Change Education Unit for grant administration and coordination.

- Ongoing multi-year state appropriations ensure continuity through 2026 with opportunity to renew.

Educator and Student Outcomes:

- 2,000+ teachers engaged in professional learning through CCLCs in their first year (2023).

- Nearly half of New Jersey school districts (49 percent) directly engaged in climate curriculum development or implementation through grants.

Results and Impact to Date:

- Statewide standard across subjects; $14.225 million (FY2023–2026) in grants.

- 49 percent of LEAs engaged in the first grant round; four CCLCs deliver professional development, stipends, and place-based support.

- Clear commitment to equity and place-based education; companion guidance fills gaps for ELA and Math, though accountability measures are still evolving.

Case Study: San Mateo County, California and Ten Strands

California has long been a leader in all things green, so it is no surprise that it’s also at the forefront of climate and environmental literacy in K–12 education. Beginning with the passage of AB 1548 in 2003, which established California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs) and led to the development of the Education and Environment Initiative (EEI) curriculum, the state laid one of the earliest and most comprehensive policy foundations for K–12 environmental literacy in the nation. Over the next two decades, this groundwork evolved through legislative actions, strategic planning, and cross-sector partnerships to embed environmental and climate literacy across standards, frameworks, and instructional materials.

At the center of the state’s current evolution is Ten Strands, an environmental literacy and climate action nonprofit that has played a catalytic role in bridging state policy, philanthropy, and local implementation. Working alongside the California Department of Education (CDE), county offices of education, and school districts, Ten Strands has helped operationalize the state’s vision through collaborative initiatives such as the Blueprint for Environmental Literacy (2015) and Seeds to Solutions (2025), a suite of free, open-access K–12 instructional resources on climate change and environmental justice co-created by the San Mateo County Office of Education, educators, community partners, and curriculum writers.

By aligning state-level policy with community-rooted implementation, advocates in California have developed a scalable, place-based model for climate and environmental literacy that integrates curriculum development, professional learning, and local engagement. Ten Strands’ leadership, linking legislative action with on-the-ground partnerships, demonstrates how nonprofit capacity and state commitment can combine to implement innovative climate literacy programs. While this is a county-level example, it could not have developed without state-level legislative precedent, and could be scaled to a statewide model. As other states look to embed climate education into their public school systems, San Mateo County offers a compelling example of how enduring impact emerges from strong policy foundations, equity-focused collaboration, and public investment.

Overview

Climate education in California is anchored in the state’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs), five foundational principles and fifteen supporting concepts about the interdependence of humans and the natural world, which were codified in law after AB1548 was signed in 2003. This bill called for the development of the EP&Cs and a model curriculum, resulting in the Education and Environment Initiative (EEI) curriculum, which was unanimously approved by the California State Board of Education in 2010. This curriculum provided educators with eighty-five model instructional units (forty science and forty-five history–social science) to help them integrate the EP&Cs into standards-based instruction. Although AB 1548 was groundbreaking in establishing a foundation, there were setbacks. The two shortcomings of the original legislation are as follows:

- It did not explicitly incorporate climate change and environmental justice, but instead focused on broader ecological relationships as principles—i.e., how people depend on, affect, and interact with natural systems. Where teaching on climate requires mention of climatology, such as climate, greenhouse gases, global warming, carbon emissions, or any processes directly tied to climate change.

- It failed to provide any meaningful mechanism with which to measure progress towards full environmental literacy statewide.

In 2015, the California Department of Education, supported by the state’s Environmental Literacy Task Force (ELTF), published the state’s first Blueprint for Environmental Literacy. The Blueprint laid out guiding principles and strategies for expanding access to high-quality environmental learning statewide.

In 2018, SB720 made it law to address the EP&Cs in future California textbooks and instructional materials, and in the state’s adopted criteria for science, history–social science, mathematics, English language arts, and other subjects, where practicable. Furthermore, SB720 closed that gap and elevated climate literacy in California’s Education Code by reaffirming the state’s commitment to statewide climate change education and referencing the Blueprint, adding climate change and environmental justice to the list of topics covered by the EP&Cs.

Aimed at advancing environmental literacy for all California students, the Blueprint outlined guiding principles and six key strategies to direct state initiatives and support local implementation by LEAs, American Indian Education Centers, and community and environmental partners. Part of the Blueprint’s vision came to life with the passage of California Assembly Bill (AB) 130, SEC 151 (2021–22), which allocated $6 million to the San Mateo County Office of Education (SMCOE) to contract for the creation of free, standardized K–12 resources on climate change and environmental justice. Ten Strands, an environmental education nonprofit and Blueprint partner, collaborated with the county office to design the program and develop a model that could be scalable for statewide implementation.

Ten Strands, an environmental education nonprofit and ELTF member that had long served as an intermediary between formal education supporters and diverse community-based, environmental education-focused organizations, was working to align their efforts and scale up their collective work. Positioned as such, Ten Strands was contracted with and partnered with by the SMCOE to arrange the creation of the K–12 resources AB 130 called for. As a backbone support and fiscal partner, Ten Strands has helped lead this effort, recruiting diverse writing teams and coordinating with statewide experts. Though they were primarily created for San Mateo County in particular, the resulting Seeds to Solutions instructional resources are designed for implementation anywhere in the state, and are ready for use to ensure that every California student has access to high-quality, standards-aligned resources. This goal is still on track, and Ten Strands is now seeking funding to provide professional learning support to teachers.

Ten Strands’ Efforts toward Statewide Implementation

California’s 2021 $6 million investment enabled SMCOE to support curriculum development, basic professional learning resources for teachers, and field testing and evaluation support. While this was a significant step forward, it was a one-time allocation. In 2024–2025, Ten Strands returned to the legislature, seeking an additional $10 million to build upon and leverage this initial investment in curricular resource development to produce statewide professional learning centered on Seeds to Solutions and to continue laying the groundwork for widespread implementation of the materials. They were not successful, and Ten Strands plans to ask for this sum again in the 2026–27 legislative cycle. This trajectory illustrates how, even though legislative commitments were made, sustaining and scaling climate literacy will require durable funding mechanisms beyond episodic appropriations. This reflects California’s broader challenge: strong policy foundations have been laid, but long-term implementation depends on stable investments.

Unfortunately, California faced a budget deficit during the last legislative cycle, and federal education funding was delayed. Fortunately, Ten Strands will ask again next year. The organization’s CEO, Karen Cowe, said, “We can do good work for $10 million, but that’s the minimum we need.” This is a drop in the bucket compared to other California education programs, such as the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP), which received more than $4 billion to expand and sustain community schools through June 30, 2031.

There has been additional bill passage besides AB 130, such as AB 285 in October 2023, which amended the California Education Code sections 51210 and 51220, requiring instruction in climate change for students in grades one through twelve and recommending immediate textbook integration. Although the bill strengthens California’s policy framework, it does not include new funding. This is not uncommon, Karen Cowe said: “Funding for implementation from the state has fallen short. For example, the state adopted NGSS in 2013, but didn’t allocate any funds for implementation until almost a decade later, in 2022. It’s the NGO community that has kept the focus on climate education going.” Luckily, the bill does reinforce expectations that climate change be integrated into instruction, building on earlier milestones such as AB 1548 and SB 720. However, it does not provide the ability to fund its implementation.

A Closer Look at Ten Strands’ Dedication to Guideline Formation and Curriculum Development

California’s Ten Strands has demonstrated admirable commitment to catalyzing and driving the implementation by leveraging the groundwork laid by state policy with a diverse implementation strategy. Though the funding necessary has not yet come through, Ten Strands has still managed to develop a model from a county-level program that can scale to the state as a whole.

Though the work that created the statewide instructional materials, Seeds to Solutions, did indeed happen in San Mateo, Karen Cowe, executive director at Ten Strands, explains that the program shouldn’t be understood as just a county-wide pilot. “San Mateo received the money from the state because it had to pass through a county or district. Then, they contracted and partnered with us to arrange for the creation of the materials. It was always understood that this was happening on behalf of the whole state,” she said. Together, Ten Strands and the San Mateo County Office of Education successfully partnered to develop instructional materials that prepare, equip, and empower students with the knowledge and skills to become environmentally literate and civically engaged individuals who take action to support their families, communities, and the planet.

SMCOE was recognized by the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE), which highlights innovative and inclusive practices that strengthen schools and support students across the state. SMCOE earned this recognition for its collaboration with the San Mateo County Sustainability Department’s Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative, which helps San Mateo County schools embed environmental literacy, sustainability, and climate-ready practices into both curriculum and campus operations. In addition, SMCOE’s resource “Climate Impact Focus Areas: Overview and Adaptation Analysis for San Mateo County TK–12 Schools” provides educational leaders, school safety officers, and emergency planners with data and strategies to strengthen climate resilience across the county’s TK–12 school communities. Beyond in-school support, SMCOE also acknowledges the impact of climate change on schools and communities through actions like holding the monthly Regionally Integrated Climate Action Planning Suite meetings and hosting the Climate Ready San Mateo County Initiative, both aimed at bringing in a multitude of voices for solutions ideation.

Thus, Ten Strands’ knowledge expertise and SMCOE’s track-record of county-wide initiatives blossomed with the $6 million allocation. The seed money created an opportunity for Ten Strands to collaborate with San Mateo to contract the creation of free, standardized K–12 resources on climate change and environmental justice. The resulting Seeds to Solutions instructional resources have been piloted by 100 teachers both in San Mateo and across the state, and are intended to ensure that every California student has access to high-quality, standards-aligned resources, beginning with the 2025–26 school year. The free K–12 Seeds to Solutions resources had over 700 teacher sign-ups in the first few weeks of the school year. Now that the instructional materials have been developed, Ten Strands is seeking additional funds to provide professional learning support to counties and school districts in support of their teachers: introducing them to the content, gathering feedback and areas to improve insights, and coordinating training.

Key Takeaways

Despite significant progress, California still faces challenges. Most climate and environmental literacy funding has been through one-time appropriations. Without sustained state-level staffing, funding, and leadership, implementation risks being fragmented and inequitable. That said, some successes have been achieved, and the groundwork for more has been laid. Below are two major initiatives that aim to have a statewide effect, though they still face funding challenges.

The first is the Environmental and Climate Change and Literacy Projects (ECCLPs), which provides glimpses into complementary philanthropic avenues for statewide PK–12 climate education. Ten Strands led the project management of ECCLPs in 2019, which culminated in a call-to-action summit at UCLA at the end of the year, and continued it in 2020 despite the pandemic. The initiative was catalyzed by that 2019 summit and by an early philanthropic investment from Stacey Nicholas, whose $3 million gift helped advance the effort. Karen Cowe, CEO of Ten Strands, serves on the executive committee that developed the proposal in 2021, leading to the project’s formal launch in 2022.

Co-led by the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems, with the University of California Irvine (UCI) School of Education serving as the program’s home, ECCLPs builds on the collective UC–CSU conferral of more than 7,000 PK–12 teaching credentials each year and the continuing education of thousands more teachers statewide. By embedding climate and environmental literacy into teacher preparation and professional learning, ECCLPs has the promise of reaching both pre-service and in-service educators across California. Formerly led by Dr. Kelley Lê and currently led by Dr. Asli Sezen-Barrie, ECCLPs continue to demonstrate how strategic collaboration can accelerate climate literacy across California’s educator workforce—even as its impact outpaces its current budget and visibility within the K–12 system. As Karen Cowe notes, “ECCLPs shows what’s possible when philanthropy and higher education join forces to prepare every teacher for a changing climate. But for this vision to reach its full potential, the state must invest alongside philanthropy—so that every UC and CSU school of education can embed climate literacy at scale.”

The second is the California Regional Environmental Education Community (CREEC) Network. Established in 1997, CREEC connects formal educators with nonformal environmental education providers. Funding from the Environmental License Plate Fund currently supports these grant-related efforts, but with only about $360,000 statewide in 2025–2026 and the average grant in 2023–2024 being $120,000 ($360,000 divided by the north, central, and south regions of California), the funds lack the strength to instill systemic changes in the state’s vast education system. Furthermore, these small project-based grant opportunities to help K–12 educators integrate environmental literacy into their own academic content areas limit eligibility to county offices of education as lead applicants, so the barrier to schools and districts if counties don’t see the need to apply is high. To date, however, both CREEC grants and the California Teachers Association’s (CTA) Institute for Teaching (IFT) are the go-to sources of funding for climate-related projects. As a supplement, Ten Strands is focused on securing funding for professional learning opportunities for Seeds to Solutions.

Together, these examples highlight both the promise of multi-sector investments in climate literacy while underscoring the need for diversified, durable funding streams that ensure such initiatives can thrive well beyond their initial seed support allowing for experimentation, responsiveness to local conditions, and cross-regional learning. “In California, we’ve had a supportive context, which is necessary, but none of it is sufficient support, given the size we are,” Karen Cowe said. “Ten Strands has raised more money since we’ve started than the state has invested into these ideas. I am grateful to the state for the investments they have made but it also is trivial considering we’re aiming to influence the educational outcomes of 5.8 million students.”

In conclusion, over the course of two decades, California has embedded environmental principles and concepts into frameworks, developed model curricula, appropriated funds for climate and environmental justice instructional resources, and launched whole-system initiatives on campuses, school grounds, and facilities. The state also illustrates both the opportunities and challenges of advancing climate education at scale. Legislation like AB 130 and AB 285 have helped embed climate literacy into standards, materials, and instructional mandates, while initiatives like ECCLPs and CREEC grants expand the ecosystem of support beyond legislation. With this framing, a mosaic of climate education strategies—early policy foundations, sustained coalition leadership, and linking curriculum with campus practices and youth engagement—are highlighted, demonstrating both the promise and the challenges of making climate literacy an enduring, equitable part of public education to prepare students for a just and resilient future. For other states seeking to integrate climate education into K–12 systems, California’s experience demonstrates that lasting impact requires not just legislative action but also diversified funding, community-rooted leadership, and the infrastructure to adapt and grow over time.

California, San Mateo County, and Ten Strands at a Glance

Duration: Four years (2023–2026)

Funding: $6 million

Highlights:

- Embedded climate standards across all K–12 subjects (with companion guidance for English Language Arts (ELA) / Math).

- Provided state grants to LEAs and established regional Climate Change Learning Collaboratives (CCLCs) for professional development, technical assistance, and place-based learning.

- Centered equity and local relevance through a Thought Leader Committee and statewide guidance.

Funding and Sustainability Measures:

- Initial $6 million state appropriation (AB 130, 2021–22) enabling curriculum development, teacher training, and evaluation through the SMCOE pilot.

- Subsequent legislative advocacy for an additional $10 million to expand professional learning and statewide implementation, demonstrating institutional follow-through and scaling intent. No legislative success thus far.

- Integration of philanthropic investment, such as Stacey Nicholas’s $3 million gift to ECCLPs, leveraging private funds to supplement limited state investment.

- CREEC Network continuity through the Environmental License Plate Fund, providing ongoing (if modest) grant support for K–12 environmental literacy projects.

Implementation and Curriculum Development Measures:

- Creation and scaling of the Seeds to Solutions K–12 instructional resources, a statewide, standards-aligned curriculum on climate change and environmental justice:

- Developed collaboratively by Ten Strands, the San Mateo County Office of Education (SMCOE), and community partners.

- Piloted by 100 teachers statewide and recorded over 600 teacher sign-ups within the first few weeks of launch.

- Made available statewide in the 2025–2026 school year, ensuring consistent, equitable access to free, high-quality climate education materials.

- Recognition of SMCOE by the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) for its Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative, integrating climate resilience and sustainability practices across curriculum and campus operations.

Results and Impact to Date:

- Seeds to Solutions K–12 curriculum developed, piloted, and released; rapid teacher sign-ups.

- Ten Strands and SMCOE built a statewide curriculum and made it publicly available.

- Impact growing, but durability depends on new, recurring funds and broader state infrastructure.

At-a-Glance Comparison of Case Studies

Key Similarities:

- All three couple state direction with local adaptability (regional intermediaries, LEAs, county offices).

- Prioritize teacher support (professional development, stipends, coaching) and open resources.

- Emphasize equity and place-based learning and partnerships with nonprofits and tribal and community organizations.

Key Differences

- Primary Lever:

-