Lessons on How States Can Ensure Hospitals Put Patients First

When it comes to regulation, New York sets itself apart from other states in its approach to corporate consolidation in hospital markets. California, where organizers have been fighting to rescue their health care from the country’s largest for-profit hospital system, stands to benefit from drawing on New York’s playbook.

After months of uncertainty, a resolution has finally been reached to save Regional Medical Center, and on April 1, this vital lifeline for East San Jose will begin its transformation. This community, whose health was once endangered by major service cuts and changes at its only major hospital, can now rest assured.

IMAGE CAPTION: The illuminated sign of San Jose’s Regional Medical Center Emergency Department on February 12, 2024. Credit: Michael Barajas via Shutterstock.

This hospital is a crucial resource for the east side of Santa Clara County, where the less fortunate ends of numerous health disparities are concentrated. For instance, Black and Latinx Medicare patients in the county have experienced higher rates of preventable hospital stays compared to the state average, and the east side of the county is home to a higher percentage of Medicaid and public health insurance patients compared to California’s state average. But over the past few years, Regional Medical Center, which has been operated by Hospital Corporation in America (HCA)—the country’s largest for-profit hospital system—since it opened in the 1990s, has been exacerbating these disparities by dramatically cutting essential services. Just last year, HCA announced its plans to shutter the hospital’s trauma center, cardiac unit, and stroke center, which would have only been the latest major cuts since the closure of the maternity ward in 2020.

View this post on Instagram

Video of Darcie Green, Latinas Contra Cancer executive director and lead organizer with the Rescue Our Medical Care Campaign, leading the crowd in the chant, “Patients over Profits!” Credit: Latina Coalition SV via Instagram.

Grassroots organizers in East San Jose launched a tenacious campaign in response, one which resulted in the county buying the hospital from HCA, a move that has effectively placed Regional Medical Center into the public’s hands. In an upcoming podcast miniseries, a key organizer in this effort and I will get into how the campaign achieved this victory; but for the present commentary, let’s zoom out and look at the big picture. Because as powerful as effective organizing can be, if the policies that govern hospital management in San Jose had been properly designed, such a campaign wouldn’t have been necessary in the first place.

What factors were missing in California that allowed a hospital, vital to thousands, to simply close essential services? Are other states and local governments managing hospitals more effectively? In fact, several states have passed laws aimed at preventing the crisis that unfolded in East San Jose. New York has a unique approach that, while not without flaws, offers valuable insights into how patient welfare can be prioritized over the interests of external stakeholders in health care.

In this analysis, we will compare the health care policies of California and New York to highlight key elements that help ensure communities maintain influence over the hospitals that serve them.

New York’s Regulation of For-Profit Hospitals Has Strengthened over Time

Whether nonprofit or for-profit, hospital systems navigate a tension between state policies aimed at reducing hospital regulations in health care and policies aimed at bolstering equitable access and quality in health care. One imagines that not even for-profit hospitals like turning away patients, or charging them more than they can afford; and by the same token, no matter how big a heart is driving a non-profit hospital, it still needs to keep the lights on.

For-profit hospitals are simply more likely to put profit first and quality or equity of care second, often at the expense of underserved communities.

But New York has been more willing than California to put meaningful limits on how a hospital can profit from service provision. For-profit hospitals are simply more likely to put profit first and quality or equity of care second, often at the expense of underserved communities. In fact, large health care companies—including for-profit hospital systems like HCA—are redistributing most of their profits back to shareholders, not patients. The Biden administration highlighted the urgent need for reform with over 2,000 concerns about corporate ownership, consolidation, private equity, and more undermining patient care and worker safety. As such, states should not expect these actors to simply line up in their own way and on their own time: they should explore more innovative ways to reduce health disparities and strengthen regulations.

IMAGE CAPTION: Picture taken May 3, 2009 of Harlem Hospital Center, a non-profit-owned hospital that opened on September 6, 1969. Credit: Jim Henderson via Wikimedia Commons.

New York’s public health laws do this by encouraging public and nonprofit ownership, and reinforce it by imposing additional regulatory measures aimed at controlling hospital expansion and maintaining service quality. A crucial element of the state’s regulatory regime is its unique usage of what’s known as a Certificate of Need (CON) law. CON laws provide states with a process by which they can ensure that the health care provision occurring within its borders actually benefits patients. The first of its kind when introduced in 1964, New York’s CON law continues to bear this mandate and aims to curb unnecessary spending and guarantee equitable access to quality care.

There are many components to the CON process. But the two most important elements for the present analysis are these: hospitals are required to pass a public need assessment for major health care changes; and hospitals cannot be owned by publicly traded for-profit providers. New York is the only state in the country with the latter stipulation.

New York’s regulatory regime has had several decades to mature. A New York Department of Health commissioner’s 1962 speech highlighted the dangerous effects of an unchecked for-profit hospital boom, warning that it jeopardized both the quality of care and the survival of nonprofit hospitals. Between 1954 and 1957, for-profit hospital beds in New York were increasing at a rate of 33 percent, compared with a 5-percent growth in non-profit beds. At the same time, only 15 out of 40 (37.5 percent) of for-profit hospitals in New York were accredited, despite receiving 70 percent of Blue Cross payments. By the 1960s, the state’s governmental priorities were expanding from merely meeting hospital service needs with advancements in vaccinations and environmental sanitation to promoting overall health care services, including mental health and disease prevention. This shift was part of a nationwide transition towards health care planning following the passage of the National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974 (NHPRDA), which provided federal funding for CON programs and required the creation of state and local health planning agencies.

IMAGE CAPTION: Source: Picture of the former Linden General Hospital, a private, for-profit hospital taken May 20, 2009. Credit: Jim Henderson via Wikimedia Commons.

Even after repeated congressional postponement of NHPRDA provisions and the eventual repeal of the act led many states to withdraw parts of their CON program, New York State saw value in the continuation of their state and regional health planning activities and persevered. Thirty-four other states have maintained their CON law in some form; California is not one of them. As New York’s CON law further evolved, the state began to focus on community health assessments, and in 1996, the New York State Public Health Council also published a report emphasizing the importance of community engagement in health care development. While California saw an acceleration in privatization, New York legislators have been comparatively more successful in the fight to keep patients at the center.

Strengths and Weaknesses of New York’s Certification Process

Certificate of Need laws are not without their critics. Some have argued that they limit competition, reduce access to care, and increase health care costs. A joint report by the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice dating back to 2004 recommended states repeal these laws due to their anticompetitive nature. However, evidence of CON laws promoting competition in inpatient care and emergency department care markets suggests that the regulatory approach can also be used to hinder predatory behavior, and researchers have also suggested that it may act as an effective antitrust tool.

New York’s certification process, and in particular its ban on publicly traded ownership, has resulted in a mandate that hospitals provide a baseline level of care.

Ultimately, it seems that the formula is flexible enough to be used in a way that protects patients, and New York has opted to do just that. While some states allow competing health care providers to veto the creation of new health care services and facilities, six CON states—including New York—do not allow that anticompetitive practice. And in general, New York’s certification process, and in particular its ban on publicly traded ownership, has resulted in a mandate that hospitals provide a baseline level of care. Providers are required to pass a character and competence review, and the recently incorporated Health Equity Impact Assessments requires a disparate impact assessment prior to the finalization of major health care changes, such as service closures and hospital mergers. These assessments were put to use to help save a birth center that was on the verge of closure after two nonprofit hospitals merged.

New York State has taken other measures to shore up the certification process. Exploring additional transparency measures is one such effort. Previously, the state increased the notification requirements for health care transactions in an effort to address private equity investment in health care, which has historically been subjected to less regulation and oversight than other health care service providers. The state is also considering a material transactions law, proposed in the governor’s 2026 budget, that would further increase the Department of Health’s authority to more closely review health care mergers and acquisitions—especially those of for-profit companies—for their impact on cost, quality, access, health equity, and competition.

With regards to indigent care more specifically, the state’s Public Health and Health Planning Council came together last year to discuss some of the much-needed reforms and improvements related to nursing homes, hospice programs, and certified home health agencies. They had been spurred on after the New York attorney general exposed four for-profit nursing homes for years of patient neglect, abuse, fraud, and profiteering. Department of Health staff noted that the public needs methodology for nursing homes was ten years out of date, which affects data collection on these services. Council members also expressed an interest in adopting standards that enable the approval of high-quality nursing home operators. These reforms would entail changes to the state’s health planning and the CON process.

California Has Tied Its Own Hands on For-Profit Hospitals

By comparison, California’s efforts to regulate for-profit ownership have been less robust. California Corporations Code Section 5914 gives the attorney general the authority to regulate nonprofit ownership of health care systems, and this power has been reinforced by that office’s successful litigation against Sutter Health, a dominant non-profit health system that had compromised care affordability and access. Federal antitrust laws also give the attorney general the power to block mergers and challenge transactions involving insurers or providers.

However, this authority does not extend to for-profit hospital transactions. As Attorney General Rob Bonta remarked, “In our settlement with Sutter Health, we were able to ensure increased transparency and end practices that decrease the accessibility and affordability of healthcare. However, we look to federal agencies and federal antitrust law to prevent potential anticompetitive mergers of for-profit hospitals and of other providers.”

Last year, landmark legislation aimed at expanding the attorney general’s authority and curtailing the expansion of for-profit hospital ownership by private equity and hedge fund groups was vetoed, further delaying much-needed regulation. The narrow application of the attorney general’s authority means that many profit-driven practices remain unchecked. As a result, the attorney general has not operated as the primary authority in cases like that of Regional Medical Center in East San Jose, where a nonprofit facility was absorbed into one of the largest for-profit health care systems in the country.

View this post on Instagram

Picture of Lives Lost Rally flyer featuring Latinas Contra Cancer and fellow organizers with the Rescue Our Medical Care campaign. Credit: Latinas Contra Cancer via Instagram.

Ironically, the governor’s veto message for this landmark legislation underscored this regulatory blindspot by indicating that the Office of Health Care Affordability should have the ability to review private equity and hedge fund transactions in health care, but given that this office cannot block transactions, the regulatory gap remains. The Office of Health Care Affordability is housed in the Department of Health Care Access and Information, which manages the state’s Hospital Equity Measures Reporting Program, and requires hospitals to submit reports measuring patient access, quality, and outcomes by race, ethnicity, language, disability status, and more. The Office of Health Care Affordability has the clear authority to review health care transactions for their cost and market impact. However, it’s a significant oversight limitation to impose the responsibility of regulating for-profit health care transactions on the Office of Health Care Affordability, which, despite having access to critical equity and market data, cannot use it to directly block potentially harmful health care transactions before they occur.

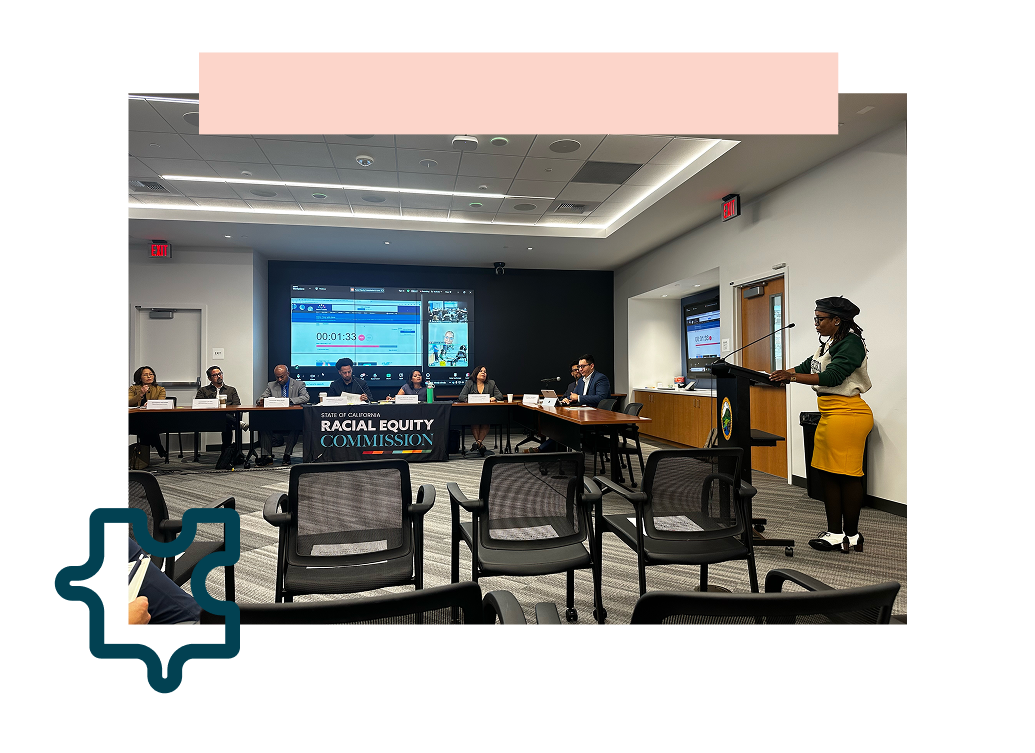

IMAGE CAPTION: Nia Johnson testifies at the September 2024 California Racial Equity Commission meeting on data considerations and the opportunities to advance racial equity. Credit: Maria Barakat.

While the Office of Health Care Affordability can make recommendations to other agencies based on the information it accesses, its inability to leverage this information to block harmful consolidations leaves vulnerable populations at greater risk of being underserved.

While the Office of Health Care Affordability can make recommendations to other agencies based on the information it accesses, its inability to leverage this information to block harmful consolidations leaves vulnerable populations at greater risk of being underserved. California has also repealed its CON law, further undermining what could’ve been the foundation of a strong regulatory measure against for-profit companies expanding into health care. Because for-profit hospitals are more likely to prioritize services that are profitable, holding these providers to a basic standard of care is necessary to ensure that patient needs are prioritized over profit motives.

Stronger Regulations Can Help Heal the System

New York continues to make progress in limiting for-profit health care abuses. Its passage of the Hospital Equity and Accountability Law is one of the newer measures established to regulate dominant hospital systems in the state. It helps lower health care costs, improve access to quality care, and prevent profit-driven companies from restricting consumer choice by banning anti-competitive practices in health care contracts and increasing price transparency. After the successful passage of this law, New York’s SEIU 32BJ, which represents property service workers like security officers and building engineers, was able to remove New York-Presbyterian from its health insurance network because they had evidence that this hospital was unfairly inflating the cost of care for their union members. Advocates, organizers, and policymakers must continue pushing for these types of reforms until profit-driven practices that undermine care are eliminated from the system.

The struggle to save San Jose’s Regional Medical Center, and to advance proactive state-level measures to prevent such crises from occurring in the first place, again highlights the urgent need for more effective regulation of hospital management, particularly in states like California, where for-profit health care systems continue to operate with limited oversight. While San Jose’s Regional Medical Center was saved, the broader issue remains: without a robust regulatory framework, these crises will continue to arise, leaving vulnerable communities at risk.

View this post on Instagram

Video of Darcie Green, Latinas Contra Cancer executive director and lead organizer with the Rescue Our Medical Care Campaign, giving a speech at the June 2024 campaign rally. Credit: Latinas Contra Cancer via Instagram.

New York’s approach offers valuable lessons, particularly in its focus on patient welfare, equity, and transparency, though it, too, is not without its challenges. States looking to build on New York’s model should keep in mind that restrictions on for-profit ownership alone are not enough to ensure higher quality care or lower cost; however, if adequately buttressed, these restrictions can serve as a foundation for addressing many health disparities, racial disparities not least among them. By drawing on New York’s model and further strengthening its own policies, California—and other states facing similar issues—can begin to ensure that hospitals remain accountable to the people they serve, rather than to profit-driven interests.