Oregon’s Direct Cash Transfer Program Proves the Model’s Promise

Oregon’s DCT+ program supports youth in securing housing, gaining employment, and building the stability to set goals and achieve their dreams. Sofie Fashana provides expert analysis, as well as recommendations for other states that are considering their own take on direct cash transfer.

Gabi was 21 when she first started receiving monthly checks as a participant of a Direct Cash Transfer (DCT) pilot program in Oregon. She had experienced homelessness throughout her life, beginning in infancy, moving constantly and rarely staying in one place for longer than a year. She recalls moving with her mother from one boyfriend’s house to another, as well as between her grandparents’ homes and her mother’s various residences. This pervasive instability forced her to adapt to new environments quickly: As Gabi puts it, “I never stayed in one place longer than a year and would move several times,” and, faced with a reality she could neither change nor control, she was forced to grow up and take on adulthood responsibilities far too quickly.

As her life went on, its challenges made Gabi’s journey even more difficult, and at one point, she and her young daughter found themselves living in a shelter in the basement of a church. As she recalled, “the shelter itself felt suffocating,” and had rules that were strict to the point of extremity. “It felt like a prison,” she would later say. Her daughter, just three months old at the time, became severely ill in the shelter, which had no proper air filtration. Even the simple act of caring for her child became a struggle. If Gabi left her room after 9:00 PM to go and get a bottle from the bathroom sink, she would face consequences. It was in these moments, trapped by the rules of a system she never chose, that Gabi realized she had to break the cycle. If not for the resources provided her by DCT and—equally importantly—the trust to use those resources as her own needs dictated and not in accordance with arbitrary or punitive restrictions, circumstances for her and her infant daughter may have continued to worsen.

Gabi was far from alone in her need for solutions like this one. With the rising costs of housing, food, and basic necessities, and in spite of existing employment and food assistance programs, more and more Americans like her are struggling to make ends meet at the most basic level. The result has been an alarming increase in homelessness. From 2023 to 2024, homelessness nationwide rose by 18 percent, with a nearly 7 percent increase in unsheltered homelessness. This represents an economic crisis as well as a growing public health emergency, as chronic homelessness contributes to long-term physical and mental health challenges that ripple across generations.

An alarming aspect of the increase in housing insecurity is the degree to which young people are affected. Across the United States, one in ten youth experience homelessness. According to the 2024 Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Point-in-Time (PIT) report, in this year alone, there has been a 10-percent increase in unaccompanied youth (individuals under 25 without parental or guardian support) experiencing homelessness in America.

In Oregon, the population of young people experiencing homelessness is one of the largest in the nation. Despite being one of the smaller U.S. states by population, Oregon ranks third in youth homelessness, right behind much larger states like New York and Texas. In Oregon, 1,315 young people are experiencing housing instability. In contrast, Texas, which has almost eight times as many people as Oregon, reported 1,355 young people experiencing housing instability. The Point-in-Time data highlight the continued work our federal, state, and local leaders need to do in order to end youth homelessness and prevent it from becoming a persistent, multi-generational issue.

In 2022, Oregon launched a Direct Cash Transfer Plus (DCT+) program as a direct intervention in exactly this crisis. The program was aimed at reducing homelessness among young people aged 18 to 24. Led by the Oregon Department of Human Services’ (ODHS) Self-Sufficiency Programs (SSP), the Youth Experiencing Homelessness Program (YEHP) initiative highlights the critical role of public investment in addressing youth homelessness. It combines direct financial support with tailored services provided by community-based organizations (CBOs), who will typically be more in touch with, and receive more trust from, young people. A handful of other states have direct cash transfer programs, but Oregon’s is one of the few which provides full public funding for the initiative. This plus the program’s successes have made Oregon’s work with DCT a national example of how housing-focused interventions can change the economic trajectory of young people who have experienced homelessness or are at risk of housing insecurity.

The purpose of this report is to analyze the effectiveness of Oregon’s pilot program by using multiple data sources, including policy roundtables, research studies, interviews, and pilot survey data, in order to define the key components of an ideal publicly funded DCT program, whether municipal or statewide, as a housing intervention for youth experiencing instability.

The Oregon case study aspects of the report will focus on three core components of the Oregon DCT+ program: 1) how effectively it helped young people and young parents secure stable housing; 2) its impact on participants’ ability to gain employment and increase their income; and 3) how DCT+ influenced participants’ ability to set and meet goals and envision a future worth looking forward to. By looking at these core areas, this report aims to inform policymakers on how to create a sustainable, effective, and youth-centered DCT model. It concludes with a set of recommendations that have been designed to be relevant for any state or local government considering starting or improving on a DCT program of their own.

Why DCT?

The direct cash transfer model is a specialized application of an approach to welfare policy with broad and varied precedent. From the COVID-19 pandemic to the Great Depression, policymakers have used cash assistance with minimal eligibility requirements to support the most vulnerable Americans during periods of grave need. Direct cash transfer differs from the aforementioned examples in that it is not bound by the duration of a national crisis, merely by the level of crisis experienced by the target population. As opposed to welfare programs like housing choice vouchers (Section 8), shelters, or host homes, which often impose strict requirements and risk pushing individuals out of services and back onto the streets, direct cash transfer commits to providing cash infusions to program participants at regular intervals—no strings attached. As with the Oregon policy discussed here, most versions also offer optional wraparound services (the “plus” aspect) to those enrolled.

The following table breaks down the different amounts across DCT programs in various locations:

Table 1

Compared to traditional, outdated approaches to addressing homelessness, which are often not trauma-informed, tend to be exclusionary, and overlook the economic realities faced by individuals and families, DCT programs are more cost-effective, require less administrative overhead, and provide young people with greater direct access to support. In 2022, Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH) published a brief assessing the statewide costs associated with services for youth experiencing homelessness in Oregon, highlighting the high expenses linked to youth homelessness and the financial benefits of investing in reducing the rate of homelessness. For example, the report shows that for every $1 invested in supportive housing for homeless youth, the state saves an estimated $3.30 in costs related to shelters, emergency health care, and the criminal justice system. Additionally, it reports that providing permanent housing and supportive services to youth at risk of homelessness could result in a 50-percent reduction in the need for emergency housing services.

For every $1 invested in supportive housing for homeless youth, the state saves an estimated $3.30 in costs related to shelters, emergency health care, and the criminal justice system.

We can see then that a proactive approach, such as housing-first models and direct cash transfer programs, can be more cost-effective than reactive crisis interventions. For example, lowering the number of young people experiencing homelessness by just a quarter could lead to significant cost savings for the state, estimated at about $16.6 million annually, according to the CSH brief. This report recommends increases in state investment in targeted programs that promote stability, self-sufficiency, and collaboration with other supportive services to end homelessness and reduce the greater cost of long-term avoidance.

The Origins and Structure of Oregon’s DCT+ Program

In 2020, the Corporation for Supportive Housing organized a series of focus groups composed of young adults who had experienced homelessness, members of community-based organizations, and representatives from state agencies, with the stated goal of addressing the housing crisis affecting young people in Oregon. During one session, participants were divided into two breakout groups: one for community-based organizations and the state and nonprofit employees in the room, and one for young people with lived experience. Each group was tasked with determining how they would invest a finite number of resources in potential housing interventions. To make the activity concrete, each group was given 100 pennies to allocate to various housing solutions, such as host homes and voucher programs.

The young people, having experienced the challenges of homelessness firsthand, understood the shortcomings of existing programs. They shared their frustration with how little individual traumas are taken into account when housing agencies determine eligibility for support, and in particular with the excessive narrowness of the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of homelessness. The young adult group recognized the urgent need for direct cash support and autonomy to make their own decisions, and in the exercise set out for them, the way they allocated their investments reflected that. When the two groups returned, the young adult group advocated for key solutions that would empower them with direct autonomy and support and without bureaucratic barriers. Their proposals coalesced around a powerful sentiment: “We just need the cash and trust.” This resonated deeply with attendees across all participating groups, and sparked collaboration among those with lived expertise, individuals with the power to fund programs, and the community-based organizations with the expertise to implement them.

This collective effort, combined with the strong research base, motivated the Oregon State Department of Self-Sufficiency (SSP) to take meaningful action and pilot the Direct Cash Transfer Plus (DCT+) program. Notably, the program was born out of an effort to truly center and understand the voices of those most affected by the issue at hand. The result was a program that went beyond simply addressing homelessness, and set a crucial precedent of empowering young people to shape the very solutions designed to support them.

The result was a program that went beyond simply addressing homelessness, and set a crucial precedent of empowering young people to shape the very solutions designed to support them.

Oregon’s DCT+ is a two-year program; its initial pilot was completed this spring, and a second pilot has been approved and will commence later in 2025. SSP partnered with three CBOs that serve homeless youth ages 18 to 24: Native American Youth and Family Services (NAYA), AntFarm, and JBarJ. Together these three organizations cover Oregon’s rural, suburban, and metropolitan areas. With national technical support from Point Source Youth and research partners Young People to The Front, SSP worked with these CBOs to select 120 participants (seventy-four by NAYA, thirty-five by JBARJ, and eleven by Ant Farm) from those already engaging with the CBOs’ services (eligibility criteria are discussed below). The case managers at the CBOs worked as the direct providers and points of contact, as well as administrators of supportive services—the plus component of DCT+.

During the first pilot, Oregon’s DCT+ paid participants $1,000 per month over the course of the two years, for a total of $24,000. The amount was developed by halving the 2022 average cost of renting a two-bedroom apartment, as determined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Fair Market Rents report for that year. (The program assumed that a young person would share an apartment with another person and cohabitate, and thus pool their monthly stipend, which together would be enough to cover rent.) In addition to the monthly payments, participants also received a one-time enrichment fund of $3,000, which they could withdraw at any time during the program. This fund was intended to cover significant costs such as housing deposits, tuition, transportation, or other essential needs. The CBO case managers also offered optional support services to participants, such as job counseling and financial planning guidance.

DCT Elsewhere in the United States

Other states have also invested in direct cash transfer programs, and while the present report is a case study of Oregon’s program and not a comparative study, it may provide useful context to briefly survey the national landscape.

DCT programs with a similar scope and mission to Oregon’s have also been piloted in San Francisco, New York City, Minnesota, and across the country, there are variations of cash assistance programs designed to support young people from transitioning out of foster care or to reduce violence through after-school cash initiatives. Many of these programs have already ended or are in the process of securing new funding, or are nearing completion. They differ significantly in scale and funding sources, ranging from private philanthropy to public dollars; as well as in duration, with some offering support for just one year, while others provide ongoing after-school stipends to help children avoid violence.

How Oregon’s DCT Program Works

The Direct Cash Transfer Plus program consists of three key benefits:

- Cash: The state provides financial support directly to program participants on a regular basis over a twenty-four-month period.

- Optional Supportive Services (the “Plus” portion of the program): Community-based organizations and their associated social workers offer counseling and guidance on issues ranging from employment to health. The type and scope of the support utilized depends on the needs expressed by participants, but may include financial coaching, housing navigation, and parenting support.

- Enrichment Fund: The state provides each participant with a one-time $3,000 payment. Participants can withdraw the sum at any time during the twenty-four-month program period

In Oregon, the eligibility and recruitment has a core set of requirements, then three tiers of prioritization for applicants. Table 2 below, adapted directly from the Oregon Department of Human Services’ guidance, glosses both the former and the latter. Potential participants could of course meet criteria from across all three tiers: they offer a rubric with which the case managers from the three partner CBOs can weigh the points in their evaluations.

Table 2

The core method with which the Oregon DCT+ program aims to create a sustainable pathway out of homelessness is through the provision of $1,000 per month and $3,000 enrichment fund, though the state also hopes that participants will make maximal use of optional supportive services as well. By addressing both immediate and systemic barriers, the program seeks to empower young people to achieve housing stability, build financial independence, and lay the groundwork for long-term success by planting the seeds for participants’ futures.

Table 3

The DCT+ program is the first of its kind in Oregon: the first direct cash transfer program, but more importantly, the first to center the principles of trust, dignity, and autonomy in how it seeks to support youth experiencing homelessness. That the financial support is provided without strings attached, and the wraparounds entirely optional, represents a shift toward truly centering youth needs and perspectives in the state’s welfare systems.

Oregon’s DCT+ is a straightforward, innovative solution to homelessness and housing insecurity. Unlike traditional housing programs, such as housing choice vouchers (Section 8), shelters, or host homes, which often impose strict requirements and risk pushing individuals out of services and back onto the streets, the DCT program takes a more flexible approach.

While the financial assistance is unconditional, the program also includes a “plus” component, which is an optional layer of supportive services. Young people can choose to engage with case managers who provide guidance, resources, and mentorship to help them navigate challenges, plan for their future, and achieve personal goals. This program requires case managers to offer support, but respect participants’ autonomy in deciding whether to access these services. The component is driven by centering trusted relationships.

Video describing the Oregon DCT+ program and its effect on one participant. Video by Derek Howard.

Data and Research Resources Used in Evaluation

I had access to a diverse set of research and data with which to produce my evaluation of the Oregon DCT+ pilot. One of them was a series of surveys produced by the research team at Young People to the Front (YPF). YPF conducted a baseline survey at the very outset of the pilot, then follow-up surveys at the six-month mark, one-year mark, two-year mark, and as the pilot was wrapping up. Participation in each of the surveys was 75 percent or higher, though some drift between surveys in the questions asked slightly limits their results. Each partner CBO, in collaboration with SSP, also conducted exit surveys. Next100 conducted a policy roundtable that included twelve participants of the pilot, and testimonies from participants were presented to the Oregon state legislature.

Figure 1

Participant Demographics and Reasons for Experiencing Homelessness

The YPF baseline survey offers us the means to paint a picture of the pilot’s participant cohort. Eighty-one of the 120 participants completed it. The resulting data present a population disproportionately affected by systemic barriers: 60 percent identified as female, 32 percent as queer, and 43 percent as Native American or Native Multiracial. Racially, 26 percent identified as white, 15 percent as Black or African American, and 8 percent as multiracial. In terms of education, 42 percent had a high school diploma, only 18 percent had education beyond high school, and 40 percent did not complete high school.

Figure 2

For most participants, homelessness began at a young age and lasted for extended periods of time. Twenty-seven percent had been homeless for less than a year at the time of entry, 61 percent had been homeless for one to four years, and 17 percent for over five years. The majority first experienced homelessness in adolescence or early adulthood, often due to structural and social factors. Over 70 percent were kicked out or left home, 22 percent fled gang violence, and 18 percent had nowhere to go after hospital discharge. About 50 percent had experienced homelessness in Portland, Oregon’s largest city, while the other 50 percent had experienced it in other Oregon counties and cities, such as Gresham, Salem, Bend, and Sandy.

Figure 3

Figure 4

How Effective Is the Oregon DCT+ Program?

This section evaluates the effectiveness of the Direct Cash Transfer Plus (DCT+) program in supporting young people across three key criteria: housing stability, employment and income, and increase in participants’ ability to dream, plan, and envision their own future. It draws on multiple data sources: the four rounds of surveys conducted by Young People to the Front; author interviews with program participants; and participants’ reflections shared during a policy roundtable facilitated by Next100 in October 2024, in which young people and experts came together to reflect on the long-term impact of the Oregon pilot program.

How effective was the DCT+ pilot helping participants to acquire secure and stable homes?

The DCT+ pilot was effective as a housing intervention for young people who were experiencing housing instability in Oregon. A total of 120 young people enrolled in the DCT program, and 117 completed it, with 91 percent reporting stable housing at the time of the exit survey, according to the Oregon Youth Experiencing Homelessness Program (YEHP) teams. One participant, whose words were shared by the YEHP team before the Oregon’s Joint Ways and Means Committee, put it this way: “The DCT program is how I’m still alive. If I hadn’t had that support at the beginning, I’d still be stuck in homelessness… DCT gave me a reliable resource and it’s the reason I could eat after going a week without food, why I was warm, and why I had a slice of freedom at the end of the night.” For this participant as well as for others, the monthly stipend was able to help these young people leave the streets and find some security after the trauma of being kicked out of homes, domestic violence, and/or familial instability.

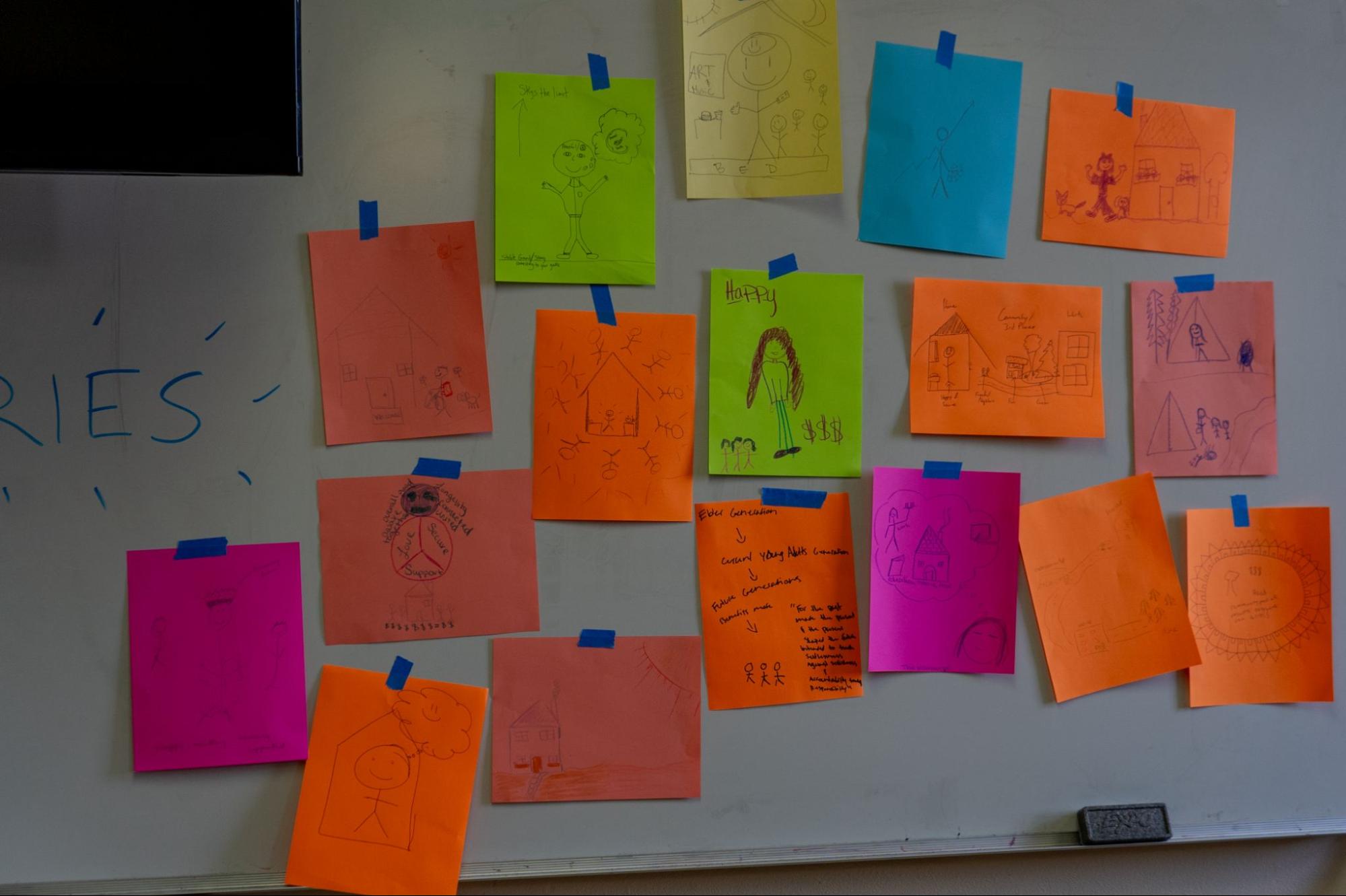

Caption: DCT+ participants at the Next100 October 2024 policy roundtable in Oregon drew people who were housed, receiving keys to an apartment, and generally being happy. These participants expressed satisfaction and empowerment in the autonomy afforded by DCT. Photo by Rudrani Ghosh.

Testimonies submitted as part of the series of surveys corroborate what the data demonstrate in terms of the effectiveness of securing housing for the young people in the pilot program. Testimony after testimony described how DCT+ led to a sense of stability as a result of being housed first. As one young adult put it,

Me and my partner were able to get an apartment recently and it’s been because of the checks coming in every month. We are now housed and no longer homeless—just as stable as we can be. But that’s something more than what we had.

Another shared, “In a beautiful apartment, in a low-income housing community—we just stick to ourselves and help those who are good when in need. We eat awesome, healthy meals, and love and appreciate every day.”

Even with these successes for the majority of the participants, housing remained a challenge for some. Some youth were still facing eviction or living paycheck to paycheck. One said, “I’m behind on rent currently and working to get help from coordinated housing.” Although homelessness dropped from 30 percent to 9 percent by the end of the program, some young people still felt like they were hanging on by a thread. DCT+ created real change, but the results demonstrate that some young people still need more time, more support, and more stability than a twenty-four-month program can offer in order for them to get where they want to be, especially given the rising cost of housing, food, and other basic needs. Fifty-four percent of the group reported that they were “unsure” or “No, I don’t feel I am able to maintain” their current housing situation.

While this is an encouraging outcome, it also raises an important question: what does it actually mean to be “stably housed?” In interviews with case managers, a common concern was the lack of a clear, shared definition of term among service providers and across state and national partners. Without a consistent understanding, it is hard to compare results across regions or fully understand who is being housed and who is still falling through the cracks.

In interviews with case managers, a common concern was the lack of a clear, shared definition of term among service providers and across state and national partners.

We already know that the monthly amount of $1,000 was not enough alone to cover rent, given that the market tends to demand much more than $1,000 dollars for an apartment. According to Apartmentslist, the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Portland is $1,380, which is almost $400 more than the monthly stipend. Many participants, especially young parents, expressed the need for housing that can accommodate family life and avoids shared living arrangements: while not a requirement in letter, in practice, the stipend amount all but requires cohabitation with someone else who can contribute to the rent. And yet, the current stipend levels were based on outdated, pre-pandemic housing costs. For comparison, San Francisco’s DCT program adjusted their cash transfers post-pandemic to account for inflation, while Oregon and New York did not.

And yet, program participants still reported satisfaction with the program overall. As mentioned above, 94 percent of youth reported that DCT+ helped them feel more stable, while only 7 percent were unsure or disagreed. In one-on-one conversations with young people at the policy roundtable conducted by Next100, one reason why people found stability despite the low amount of cash was due to the consistency of the monthly cash.

Many said the stability resulted from a few key aspects working in concert: cash, autonomy, support, and flexibility. Because the DCT+ money didn’t come with strict rules, young people had the freedom to use it based on their own needs. Moreover, participants used the one-time enrichment fund of $3,000 to purchase everything from putting a security deposit on an apartment to getting a car and beginning their own business. Some leaned on their case managers to help navigate the housing process—like one young person who said their case manager drove them around the city of Bend to visit apartments. Another worked with their case manager on budgeting, making sure they could stretch the cash to pay off their bills, food, rent and transportation. The flexibility of the cash gave young people autonomy over their lives, as described by one case manager at the policy roundtable:

DCT+ allowed young people’s apartment applications to be accepted a lot quicker—because the cash allowed them to easily verify their income, breaking down the barriers often associated with voucher programs.

The flexibility of the cash was also easily paired with other methods for securing housing, for participants for whom that was applicable. For example, the data shows that 28 percent of participants used both DCT+ cash and housing vouchers to secure housing. This blended approach worked well, especially in cases like that of a young person with a disability who couldn’t work full-time, but was able to access supportive housing through that pairing. These supplemental methods were especially important given that $1,000 is not enough to cover rent in the Oregon housing market. As one participant at the policy roundtable said, “I can’t find anything in Portland that is $1,000.”

Did DCT+ help young parents secure housing and unite with their children? The DCT intervention appeared to be especially impactful for participants who were parents. Over the two-year period, there was a 10-percent increase in participants who were parents or primary caregivers. Additionally, twenty-five participants who were parents lived with their children by the end of the program, compared to nineteen individuals who were living with their children at baseline. In other words, for most parent participants, housing stability for a parent translated directly to stability for their child.

Some parents were able to go back to school. Others had time and space to focus on their future and gain some breathing room, knowing that regardless, at the end of the day, they and their children had a safe place to rest. As one participant stated, “It was the beginning of general healing and breaking of a cycle.” Another young person shared, “I have an apartment in my name after years on the streets. I’m having a baby any minute now. I am so happy.” DCT+ engendered a sense of stability for participants because it meant consistent cash for two years. In one case, it also offered the confidence that allowed a young mom to escape domestic abuse and gave her the security she needed from violence.

At the policy roundtable, one young parent shared how DCT+ helped her secure housing for herself and her daughter. She appreciated the program’s flexibility, noting that she was able to use her $3,000 enrichment fund for a security deposit. Other housing programs, such as Section 8 housing choice vouchers (Section 8), shelters, or host homes, are often one-size-fits-all.

Another parent shared, “Before this program, I was so stressed out, I’d walk with my daughter just to cope and even then, I’d still break down. I’m super appreciative to be given the chance to breathe, but definitely unsure about what happens when DCT ends.” Many young parents echoed this tension: they were grateful for the immediate stability, but were aware that the cost of rent, bills, and basic needs for their children would continue beyond the program. For them, the two years was a great start to stability, but worried that it might not be enough.

How effective was the DCT pilot in enabling participants to secure employment and increase income?

It is important to note that the original purpose of the DCT+ program was to provide an opportunity for the target population to secure stable housing, not necessarily to secure employment or increased income. Nonetheless, the pilot had an impact on these variables as well.

Despite improvements in housing stability, the outcomes tracked in the surveys related to employment and income were mixed. On one hand, average monthly income increased significantly, rising from $614.15 at the start of the program to $2,059 by the end—a 235-percent increase for which the stipend alone could not entirely account for. On the other hand, overall employment status did not show a similarly dramatic shift.

At baseline, only 16 percent of participants were employed full-time. By the end of the program, this increased to 24 percent. Among the participants who responded to the survey, 40 percent reported working in some capacity (full-time, part-time, or informal jobs), while 52 percent reported being unemployed. These data seem on the surface to conflict: while employment rates remained relatively similar, incomes rose. One possible explanation is that those who were able to secure or maintain employment did so at higher wages, or some young people counted the DCT+ monthly amount as income. The available data are inconclusive on this count.

The variation in individual employment experiences was also striking. For example, one young person reported in a survey response: “Current stable full-time employment (35+ hrs/week). Making above minimum wage.” In contrast, another noted they were currently on leave due to an upcoming childbirth. This aligns with findings from the Oregon pilot program’s exit surveys, where a high percentage of participants became new parents, which may have temporarily impacted their ability to work.

One possibility is that the mixed outcomes in employment are partly tied to inconsistent participation in the program’s “plus” component, which includes supportive services such as career or job counseling that young people can access, request, and to some degree customize to their needs. Another is that those supportive services may have been inconsistent themselves in their results. Contributing factors may include limited partnerships between the housing sector and employment opportunities, frequent staff turnover, inconsistent communication, and a lack of clear accountability for supporting participants in their employment goals, but the data are lacking for a definitive conclusion. For example, case managers reported that it was difficult to incentivize young people to come to the supportive services—typically only two to five people participated in each. They hypothesized that this was because the services were entirely optional and that the program participants were already incredibly busy. During interviews with twelve program participants during the roundtable, they emphasized the need for one-on-one support over group sessions.

In the YPF surveys, young people were asked how they searched for jobs in the last year of the program (see Figure 5 below).

Figure 5

When asked why they weren’t working, six young people talked about not being able to find jobs, lack of child care, disability status, or health issues. One participant said, “I’ve had about 3 jobs in the past 3 months that were unable to accommodate my autism and let me go within 2–4 weeks.”

Transportation also came up over and over again as a significant barrier. So did lack of work experience, especially for young women, echoing what McKinsey found in their American Opportunity Survey: many emerging adults feel stuck applying to jobs when they don’t meet every single requirement; and oftentimes, they simply don’t know where to start. It’s hard for young people to secure employment, and they can often benefit from social and logistical guidance.

Thus, while granting that employment and economic mobility were not direct goals of the DCT+ program, these goals are inextricably linked with housing stability, and we cannot see any definitive improvement in them in the results. As we will discuss in the recommendations section below, more attention should be given to these intersections in Oregon’s future DCT implementations and in any program that other states decide to take on. These data reflect the survey results from the sixty-two participants who consistently responded to the related questions in the Young People to the Front surveys.

When participants self-assessed their ability to budget effectively and asked how well they were budgeting and the frequency with which they were able to follow that budget, there was a 19-percent increase in moderately following a budget, while there was a 6 percent increase in feeling confident to follow a budget by the end of the twenty-four months. As expenses and the cost of living increased, a provider explained that budgeting felt challenging for the young people because most participants’ DCT+ money went towards basic needs like housing and utilities. However, this provider emphasized that they made continuous efforts to assist with budgeting, and according to the survey conducted by Young People to the Front, from baseline to the two-year mark, there was a 23-percent increase in the number of young people reporting that they had attended a budgeting or financial literacy workshop out of the sixty-one young people who filled out the form, compared to baseline 36.5 percent. As one case manager said,

During the Point Source Youth conference on DCT, one participant came out of a session absolutely energized. He showed me his notebook, which was filled with numbers and notes he had just taken. As he shared them with me and a few others, he said that the session helped him realize what he should have done when he first received his DCT+ funds. His eyes were lit up and you could see how inspired he was to take what he had just learned.

The YPF survey data tells us that, at the six-month and twelve-month marks of the DCT+ program, the policy roundtable gathering found that the most common sources of debt for participants included phone bills, utilities, housing expenses, unpaid medical bills, student loans, and overdraft fees.

With the possible exception of student loans, these are basic costs that, for many young adults, are covered by parents or guardians. In fact, a national poll found that 32 percent of young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 still have their phone bills and streaming services paid by their families. And a 2024 survey revealed that 60 percent of Gen Z youth receive financial support from their families for rent and utilities.

Figure 6

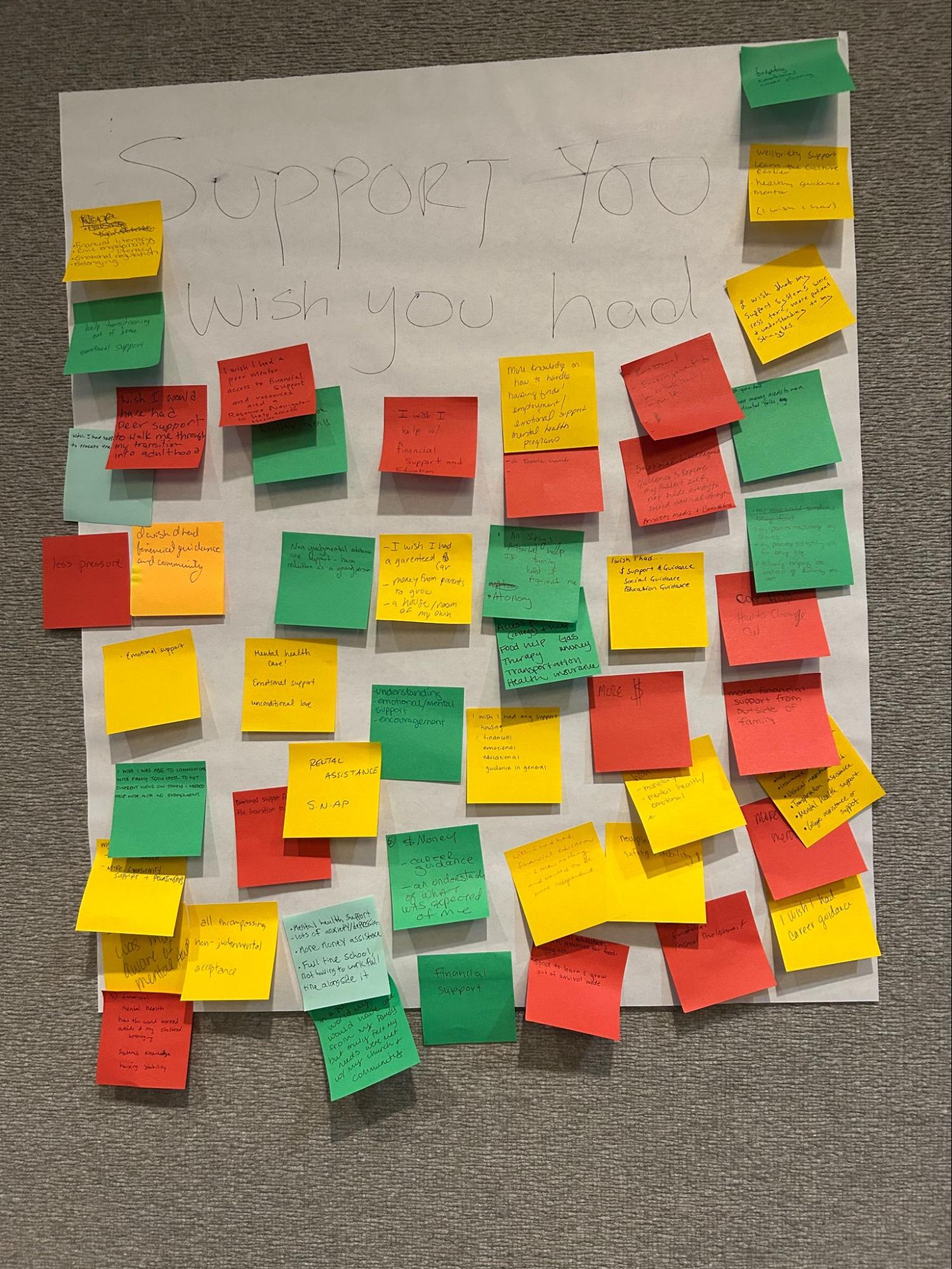

This is an image of Post-It notes on which service providers, young people, and policymakers wrote down support they wished they had during emerging adulthood. Many identified wishing they had more support with basic necessities like food, clothing, housing, transportation, and health services during that period. Photo by Sofie Fashana.

For many DCT+ participants, these everyday expenses quickly turn into burdensome debt. In today’s world, phones and the internet are not luxuries: rather, they are essentials for applying to jobs, staying in school, accessing services, and staying safe. Suggesting that young people should go without these essential resources or shoulder the burden of debt alone is both harmful and a barrier to long-term economic stability.

How did DCT+ affect participants’ capacity to plan for and envision their own futures?

Many of the young people in the program reported personal goals they were actively working towards, such as improving their mental health, securing employment, going back to school, increasing their savings, or building independence and preparing for adulthood.

When young people are solely focused on finding their next meal or a safe place to sleep, they find it harder to imagine taking strategic risks or making long-term plans. Without basic needs like food, shelter, clothing, and a consistent sense of safety, setting goals is a privilege rather than a guarantee.

For example, when asked, the young people participating in DCT+ spoke openly about the dreams they had. One young person said, “I plan to finish getting my diploma and then continue working while also exploring my possible career paths.” At the six-month mark, 23 percent of respondents said their primary goal was to secure employment and grow their savings.

Beyond jobs and savings, many talked about actively caring for their mental health, maintaining stable housing, and gaining more independence, whether preparing for parenthood or learning to drive in order to open up new job opportunities. At the roundtable, one young man shared that his top goal was earning his driver’s license, explaining that without it, he was limited in where he could consider working.

At the Next100 policy roundtable, DCT+ recipients envisioned how they would allocate cash for various needs. This was a space for them to design the services that would allow them to dream and set goals for their own futures. Photo by Rudrani Ghosh.

Participants in the Next100-facilitated policy roundtable overwhelmingly agreed that meeting basic needs is a fundamental requirement for young people to move beyond survival mode—needs for which most other youth their age can rely on their parents or guardians. Without stable housing, access to food, and health care, the program participants often felt stuck in a “fight, flight, or freeze” state, unable to focus on long-term planning. Participants highlighted the need to address systemic barriers like housing, education, and employment so that they could channel their energy into building their futures. Programs should support individuals in removing immediate obstacles while allowing them the flexibility and resources to create personalized solutions.

DCT+ supports young people by meeting their basic needs through services and case management, giving them the foundation to dream and plan. It mirrors the kind of guidance and stability that all young people need and deserve as they develop and embark on their adult lives.

Evaluation Summary

Evidence from Oregon and similar programs shows that DCT+ helped young people secure housing, especially when paired with voucher programs. By the end of the program, 92 percent of participants were housed, and the flexible design helped parents meet their needs. However, cash alone is not enough. Young people also need tailored support services, community connections, and long-term guidance to navigate adulthood. Short-term programs can be relieving, but lasting economic mobility for emerging adults requires ongoing investment. Finally, integrating partners such as providers of workforce development is essential, since many young people wanted to work but faced barriers to entering the job market.

Recommendations

These recommendations are rooted in insights the author has gleaned from a variety of interactions with Oregon’s DCT+ participants and facilitators: one-on-one conversations between program evaluators and each participating organization’s case managers; the policy roundtable, which included twelve participants from all three DCT+ sites in Oregon; and the author’s analysis of program survey data. They also draw on conversations and interviews with national policy advocates, DCT leaders, and legislative staff. These recommendations are not directed at Oregon’s program alone: rather, they are tailored to the needs of any city or state currently implementing, or considering implementing, a DCT program targeted at young people facing housing insecurity. The recommendations represent thirteen core elements of a successful DCT program for this population.

1. Structure the Program in Order to Facilitate the Principles of Trust, Participant Autonomy, and Accessibility

One of the key parts of this program was the flexibility it gave young people. Direct cash support meant they had the autonomy to find housing on their own terms, and had a consistent income they were able to show to landlords, making the barriers to access housing a lot easier. At the same time, the program required providers to offer supportive services, though participation was optional. Some young people leaned on those services, while others preferred navigating things on their own. The supportive services are something future programs need to invest in making them more effective, meaningful, and accessible, and which need to be better documented so we can assess their impact. Additionally, the benefits of coaching was one thing both participants and case managers wished they had a clear understanding of.

The participants especially appreciated the enrichment fund, and many shared how critical it was in putting money toward housing, starting a business, or even buying a car.

2. Define “Stable Housing” Clearly for All Program Sites and Purposes

DCT programs must establish a single clear, standardized definition of “stable housing” across all program sites. In the Oregon DCT+ pilot, case managers reported that there was no consistent definition of what “stable housing” means for the participants. One provider explained that the definition was sometimes so broad that it meant very little in practice, and seemed only to serve as a way for the state to inflate the number of people officially classified as “housed.” The definition could include, for instance, youth who were couch-surfing for more than thirty days or living with roommates but no permanent place of their own, and therefore had no mental stability and peace of mind. This ambiguity makes it difficult to measure progress or tailor services effectively. The program should not focus so heavily on achieving a high percentage of housed individuals that the definitions being used conflict with what it actually means for a young person to be truly housed.

A key step in clearly defining stability is to ask young people in the program how they understand it, both at the beginning and midpoint, to see how their definitions grow and change over time, and regularly gather feedback on whether the program’s definition of stable housing aligns with participants’ understanding. For example, someone might be staying with friends but constantly fear being kicked out if they do anything wrong. While better than a train station or a bus stop, this is still a stressful and unstable living situation. A young person should feel that the place they are staying in is just as much theirs as it is for the other people living there.

A young person should feel that the place they are staying in is just as much theirs as it is for the other people living there.

The program’s definition of stability should also align with broad, inclusive definitions of homelessness, like those in the McKinney-Vento Act. This law not only recognizes young people without homes, but also those living in shelters, motels, or temporarily sharing housing due to the loss of stable housing. Finally, when defining “stable housing” for young adults, it’s essential to consider the natural movement and frequent transitions that are typical during emerging adulthood. The definition should reflect this mobility and also allow for culturally diverse understandings of stability.

3. Align Technical Assistance to Prepare Staff to Support with Real Needs

Technical assistance (TA) providers in DCT+ programs should prioritize collaborating with local organizations to tailor solutions that align with community needs and youth realities. This includes offering targeted training, improving data collection systems, and fostering sustainable practices for long-term program success. Additionally, TA should establish feedback loops and peer networks to continuously improve the program, ensuring local providers have the resources and support to effectively engage and support youth. Staff from CBOs should have clearly defined roles and receive continuous training based on the needs of the staff and program.

Moreover, the role of TA must be clearly defined to ensure it meets the needs of providers and program staff. TA should include support for understanding and implementing the DCT+ model, navigating challenges, benefits coaching, and adapting practices to fit local contexts.

Facilitators of TA should work in close collaboration with case managers, not as supervisors or directors, but as thought partners. This partnership should center case managers and state administrators, while providing support for case managers. DCT programs must prioritize spaces where case managers can share honest feedback, receive meaningful support, and exchange ideas. A structured feedback mechanism (e.g., quarterly feedback surveys, focus groups, or peer learning circles) would help TA providers tailor support and continuously improve program implementation.

4. Calculate the “Cash” Element of DCT+ Accurately and Supplement Monthly Income

The $1,000-per-month amount provided by the Oregon pilot does not reflect the true cost of housing in the cities that participants inhabit. Future programs should factor inflation and local cost of living into their financial models as well as increase their one time enrichment funds. As one young person said during the policy roundtable, “You won’t find anything in Portland Oregon for $1,000 dollars.” For example, the San Francisco program calculated its monthly amount based on the city’s current cost of living, while Oregon’s estimates were based on pandemic-era costs. Additionally, shared housing does not work for everyone. Many young people in Oregon had families of their own, and relying on a monthly amount based on the assumption of shared space is not an effective policy. It does not fully meet the individual needs of young people and can overlook their unique living situations.

Additionally, to support financial stability after the program ends, programs should encourage and support participants in building up savings. To help young people build savings without taking away their control, programs can offer flexible, youth-driven options. For instance, in the last six months of the DCT program, participants could choose to set aside a portion of their stipend: say, $100 a month into a personal savings account. Programs could then match those contributions to encourage saving. By the end of the six months, the participant would have a savings account they can draw from when they finish the program, a similar model to the Family Self-Sufficiency matching program. This will help participants build a small financial cushion to rely on once the two-year cash support ends, reducing the fear and instability young people associate with the program’s conclusion.

5. Prioritize Providing Guidance Conversations in Advance of Enrichment Fund Withdrawals

Participants in the Oregon pilot emphasized the importance of having conversations with their case managers before receiving their one-time enrichment funds of $3,000. These conversations should be focused on planning and tailored to each young person’s unique needs and goals early in the program. At the same time, DCT programs should continue to prioritize flexibility and autonomy on the ways funds are used while finding a balance with intentional support, such as financial coaching, budgeting assistance, and help with opening bank accounts, to ensure young people are fully prepared to manage their funds responsibly.

6. Foster More In-Person Community and Create More Cultural Connection Opportunities

In my conversations with young people as well as with providers, there was appreciation of and need for more in-person community opportunities. DCT programs should make sure there is space for participants at the various DCT sites to connect with one another, both in-person and virtually. For example, Oregon could facilitate quarterly in-person meetups for program participants, as well as onboarding gatherings for organizational staff. These events should provide opportunities for staff across sites to build relationships, connect with the YEHP team and technical assistance providers as a checkpoint on what is going well and what can be changed. Additionally, hosting a mid-program, statewide gathering for young people who are participants of DCT+ could be helpful in making sure there is a check point. This could be structured around a job fair or career workshop, with breakout sessions focused on resume support, job readiness, and networking and wraparound services. Local experts could also be invited to lead this as that was something that was a want among all the organizations.

The program should also create a shared Instagram or similar social media platform for current DCT+ organizations and participants. This space can be used to post general updates, share resources, and promote upcoming events and activities, helping to foster connection and keep everyone informed. There could be one for the state that has everyone on the platform, where they post general information about the program, and another one where each location could create or identify the best platform for communication for their appropriate site.

7. Extend the Supportive Services beyond the End of the Program, and Reduce and Improve Case Loads

While the direct cash component of DCT+ in Oregon’s pilot was limited to two years because of funding constraints, participants consistently expressed that two years is not sufficient to fully exit poverty or establish long-term stability. DCT+ models should include continued access to supportive services, such as case management, one-on-one support, peer support, mental health care, education, and employment resources, especially if programs can only provide cash stipends for short, defined periods of time. Extending the “plus” component ensures that young people remain connected to a continuum of care like housing support, career coaching, mental health resources even after cash assistance ends.

That said, both during and after the program period proper, case managers should not be responsible for more than fifteen young people at a time. A smaller caseload allows staff to build stronger relationships, tailor support to each individual, and avoid burnout. This case load also creates space for one-on-one relationship building as well as mentorship. Both sides of the relationship would benefit.

Low participation in supportive services was a consistent theme across the Oregon pilot sites. For DCT+ programs, greater emphasis must be placed on making these services a central, integrated part of the program. Both Oregon DCT+ case managers and participants recommended monthly in-person check-ins, whether that was grabbing lunch, budgeting together, or discussing personal goals. They thought that these should be a required form of engagement beyond simply confirming receipt of funds. They also recommended them as a more effective way to build relationships than more formal workshops.

To address low attendance at events and workshops that providers plan, DCT+ programs should introduce a set of required foundational workshops (e.g., financial literacy, goal setting, or career development). Many case managers expressed frustration with poor turnout, and requiring select sessions would provide structure while giving young people access to vital resources. At the same time, providers should not rely on workshops as their primary method of engagement. True connection happens through consistent one-on-one relationships and meaningful peer-to-peer support, not just through scheduled sessions.

8. Center Youth Voices

The program must ensure that young people with lived experience are meaningfully involved in program design, decision-making, implementation, and the work of the research team itself. Truly making youth your partners is essential for success. Refer to this manual on how to best engage and integrate young people into your work.

Youth participants of Oregon DCT+ at a Point Sources Youths convening in Oregon, where they shared and advocated for DCT for other young people and discussed the effectiveness of the program in their lives. Photo credit: Point Source Youth Conference.

9. Build Stronger Partnerships with Local Education and Workforce Systems

CBOs should collaborate with local job training programs, employers, and educational institutions to deliver wraparound services. Case managers are not always experts in education and workforce issues, and having local partners provide educational and workforce training would be beneficial for both the participants and the CBOs. For example, some of the support young people in the Oregon program wished for was access to schools to get their GRE, driving schools, career training and employment support, and programs that helped them start their own business.

10. Standardize and Strengthen Benefits Coaching

Developing and implementing clear, accessible guidelines for benefits coaching is crucial to DCT programs’ success. Everyone in the program, including providers, technical assistance teams, and participants should understand how benefits (SNAP, TANF, Child Care, etc.) are affected by monthly stipends and how to navigate them without losing critical support. Cities and states should have specific guidance materials that are easy to access. Cities and states should also look at avenues to braid private and public money together in order to protect participants’ SNAP and SSI benefits.

Some of the benefits of coaching conversation should also include providing local resources to young people. The program and organizations should create a shared data base that maps available resources across the state, including details on eligibility, application processes, and updated website links to ensure young people can easily access them.

11. Support Youth Who Are Parents Themselves

Given the number of housing-insecure youth with children, child care and family support must be top of mind for programming. A DCT+ program greatly enhances participant outcomes when providing child care and family support for young people who participate in the program. Providing space for parents to meet one another and create a sense of community would also increase the likelihood of success for each participant. For example, the Oregon DCT+ survey results highlighted that one reason for unemployment was child care challenges. This could be addressed by providing child care options and related resources for young people, many of whom are single parents.

12. Facilitate In-Program Peer-To-Peer Support

DCT programs should connect participants with other young people who have had similar experiences, such as alumni of DCT+ programs or current participants. A peer-to-peer support program using similar frameworks, such as the recovery peer advocate model, as opposed to a traditional case management system, provides the opportunity for participants to see and be seen by each other. For this peer-to-peer programming, there should be a clear training plan and well-defined expectations for both the young people and the mentors. As a recent mentor told me, “I am never going to stop being in your business,” a sentiment that perfectly captures the role of a mentor: someone who consistently shows up, stays curious, and genuinely cares about what matters to the young person.

13. Use Trauma-Informed Data Research Methods and Prioritize Data Security

Any research questions and surveys that are used to evaluate a DCT program should be vetted by the target group, as well as case managers who work directly with the participants. It is important that the research team is mindful and makes sure to center young people as individuals and not as numbers. Additionally, there should be a limited number of people or organizations who have access to the data. Data must be accurately and transparently reported.

Conclusion

Once Gabi began to participate in the Oregon DCT+ program, she was able to secure a home for herself and her daughter. This achievement was something she had never experienced with her own mother: as she reflected back on her experience, she said, “I could breathe.” Now she was creating the memories for her daughter she wished she had had during her own childhood. She knew she could not let the struggle and reality of her mom’s past become her story, or her daughter’s. She was determined to find a way out of that cycle, and DCT+ was one way she was able to find consistent income and afford monthly rent.

Ultimately, the Oregon DCT+ program proved to be an effective tool for supporting housing stability, with 91 percent of participating young people self-identifying as stably housed by the end of the twenty-four-month pilot. Young people cited the flexibility and unconditional nature of the cash transfer as key factors in the program’s success, alongside the optional supportive services that some participants were able to access.

However, findings also highlight the need to strengthen the supportive service component, particularly in how providers engage young people and how guidance is offered to participants throughout the program. The pilot offers valuable lessons for the future of DCT+ in Oregon and elsewhere, especially regarding how technical assistance can be better structured to provide targeted support, align with provider needs, and reflect the lived experiences of young people. It is critical to also consider how education and workforce training, as well as benefits coaching can be refined and expanded to protect the financial well-being of participants and help them build long-term stability.

On the whole, the experience in Oregon demonstrates the tremendous promise of DCT policies. Here’s hoping that state and local governments across the country join in on the growing trend.