Inclusive Policy Research and Policy Development with Impacted Communities

A Toolkit for Think Tanks, Policy Nonprofits, and Governments

Francisco Miguel Araiza Suryani Dewa Ayu Emma Vadehra“When I think of myself as proximate to these communities, it means I hold this community with dignity, it means I understand there is value in what they have to say, it means that they are ultimately influencing my thinking, their perspectives have shaped how I see the world. I continue to recognize that there is guidance within the community, there’s knowledge that needs to be taken into account.”

—Rosario Quiroz Villareal, Next100 alumna policy entrepreneur

Introduction

This toolkit was developed with generous support from Lumina Foundation.

Public policy is so ubiquitous that it is frequently unnoticeable. It helps determine the quality of the education we receive, the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat, as well as where we build, what we build, and who builds it. In other words, despite its sometimes undetectable presence, public policy impacts each of us, every day.

However, the impact of our public policies are not felt equally. Too often, our public policy choices, decisions to change or maintain the status quo, disproportionately negatively impact or even harm individuals and communities that have also been historically excluded—because of their race, ethnicity, or immigration status; due to their age, educational attainment, income, or gender identity or expression; or any number of other factors—from full participation in many facets of our society. Nowhere is the exclusion of directly impacted communities more indefensible than in our democracy and policymaking process, the precise forums where decisions are made about how to prioritize, develop, and implement the solutions to our collective problems.

Nowhere is the exclusion of directly impacted communities more indefensible than in our democracy and policymaking process, the precise forums where decisions are made about how to prioritize, develop, and implement the solutions to our collective problems.

And the egregiousness of that exclusion only grows as the scale of many of our toughest public policy challenges—such as climate change and income inequality—intensifies. Because not only is the complexity and size of our societal problems increasing, so are the impacts on individuals and communities. Climate change will inevitably harm all communities, but communities of color are most negatively impacted by it now, and their risk—along with the risk to low-income communities, individuals with less than a high school education, and seniors—is projected to increase even more as climate change worsens. Similarly, economic inequality has a negative impact on national economic growth, but disparities are often more deeply felt depending on a person’s racial and ethnic background. Even newer challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have divergent impacts based on pre-existing racial and ethnic inequities. Furthermore, it is increasingly clear that climate change will not end, nor will economic justice be achieved—for Black people, people with disabilities, or any number of individuals who experience economic insecurity—without public policy and government action. For all these reasons, it is time to increase the engagement and empowerment of directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development.

A summary of the recommendations that appear in this toolkit is here.

Why it is essential to engage directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development.

There is a moral imperative to engage directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development, both to affirm and learn from the expertise of individuals with lived experience and as a lynchpin for a more democratic and just society. It is often said that experience is the best teacher, yet the policy sector undervalues the wisdom that directly impacted communities have accumulated through experiencing policy decisions and their consequences firsthand, by excluding them from policy work and and policymaking roles. Next100 previously developed a toolkit on concrete actions policy sector organizations can take to address the historical exclusion of individuals from policymaking roles: “Building a More Diverse, Inclusive and Effective Policy Sector: A Toolkit for Think Tanks, Policy Nonprofits, and Governments.” In this toolkit we focus on how policy sector organizations can engage directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development.

Engaging with directly impacted communities demonstrates that the public policy sector values the experiences, perspectives, and voices of individuals and communities with the most at stake in public policy choices. In addition, it addresses the historic and systemic exclusion of marginalized communities in the public policy space. Both of these are worthy goals on their own merits. However, not only is creating more inclusive policy research and policy development practices the right thing to do, but also it will add significant value to each process.

At its most basic level, including directly impacted individuals and communities in policy research and policy development will increase the policy sector’s collective capacity to address social problems. The policy sector (and society at large) will have more eyes, ears, hands, and minds grappling with the most pressing public policy problems. Furthermore, making policy research and policy development practices more inclusive will bring a much-needed diversity in skills, knowledge, and perspectives, all of which will be informed by the unique lived experience of individuals who are most impacted not only by the issues policymakers are trying to solve, but also the policies they have implemented to solve them. More broadly, there is a substantial body of research that demonstrates the benefits and impact of diverse partnerships on problem solving, which is, in part, what directly impacted individuals will bring to policy work. Research demonstrates that racial and ethnic diversity and gender diversity, in private sector organizations and in a multitude of social science experiments, have positive impacts. Policy research and policy development that is driven by diverse and inclusive partnerships between policy sector organizations and directly impacted communities have the potential to significantly improve our policies and our democracy.

Furthermore, engaging impacted individuals and communities in policy making will help to build their trust in the ability of government—and the policy sector more broadly—to find solutions to the problems that most affect them. Trust in government is necessary for a democratic and just society—it drives political engagement and maintains faith in democratic institutions—and so the need to build and maintain this trust cannot be overstated. But trust in government is waning: in a survey Next100 conducted in partnership with GenForward in winter 2021, we found plenty of evidence of a disconnect between diverse young adults and government, and skepticism towards government’s ability to drive change. For example, the data revealed low levels of trust in federal, state, and local governments among young adults. In addition, working for the government was rated as one of the least effective methods for making change in their community—in fact, signing a petition is seen as more effective than working for the government.

Engaging impacted individuals and communities in policy making will help to build their trust in the ability of government—and the policy sector more broadly—to find solutions to the problems that most affect them.

Unsurprisingly, the lack of trust in government translates into disinterest in government careers and low levels of democratic engagement—only about half of respondents considered themselves politically active or engaged. However, the survey also demonstrated that an overwhelming majority of young adults, more than 60 percent, are more likely to trust government when they see their communities reflected in government. Policy sector organizations can do their part to close this representation gap and mend the rift between our democratic and government institutions by engaging directly impacted communities and ensuring that policy agendas reflect the needs and priorities of those communities.

If policy sector organizations work to increase the inclusion and equitable participation of directly impacted communities in the policy research and policy development process, they will be doing their part to improve trust in government and improve its effectiveness as a vehicle for equitable change. But to do this work effectively, policy sector organizations must commit to establishing and maintaining trust among directly impacted communities and individuals from the very start, and at every stage of the work they do.

Engaging with communities and individuals with lived experience can also bring irreplaceable and otherwise inaccessible information to the policy research and policy development process, to help identify or prioritize challenges in policy design or implementation. For example, an individual who has experienced chronic homelessness can share not only what root-cause circumstances led to their initial housing insecurity, but why current policies have not helped them become housing secure; an individual who has navigated the naturilization process can help improve the path to citizenship, explain how administrative burdens have created additional barriers, and share what other intersectional policy challenges—lack of health care, worker exploitation—they may have experienced while they were undocumented. These experiences and insights, which come from being directly impacted by societal problems and their policy solutions, will be helpful to policy sector organizations in setting priorities, defining the scope and root causes of the problem, generating innovative policy solutions, and executing effective implementation.

Including directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development also involves thinking about the work differently. Especially if, as we propose, the process is carried out with an aim toward true inclusion, collaboration, empowerment, and equity. The risk in falling short of these goals is clear: creating a process that will further marginalize, tokenize, or aim to simply placate communities who have been historically excluded from meaningful engagement in developing, advancing, and executing public policy solutions. The exclusion of impacted communities is embedded in the status quo of the policy sector and, quite frankly, across many facets of our society. Thus, what a shift toward more equitable policy requires is a fundamental change in the way the policy sector operates. This is not to suggest that including directly impacted communities is the only thing that matters in policy research and policy development; rather, it is to emphasize that including the lived experiences of individuals is a critical, and too often overlooked, part of that work and will require making intentional changes for many organizations. Those changes may be difficult because they are a step away from what is comfortable and familiar. To help ease the transformational shift from the status quo to this less known, but necessary, exciting, and more equitable future, we have developed this toolkit, which brings together practices from across multiple sources and our own experience from doing this work.

The exclusion of impacted communities is embedded in the status quo of the policy sector and, quite frankly, across many facets of our society. Thus, what a shift toward more equitable policy requires is a fundamental change in the way the policy sector operates.

What led Next100 to create this toolkit?

Next100 is a policy leadership development program and start-up think tank that was created by The Century Foundation to address the systematic exclusion in the public policy sector of the communities most directly impacted by policy. We believe that addressing the systemic challenges we face as a society requires systemic policy change, and—just as importantly—that effectively developing, enacting and implementing equitable and inclusive public policies requires including individuals who have been traditionally excluded from driving policy change. We believe changing who makes policy and how policies are prioritized, developed, and implemented will lead to more effective policies and a more inclusive, democratic, and just America.

At Next100, we identify, develop, support, and learn from individuals—policy entrepreneurs (PEs)—who bring diversity, proximity to impacted communities, and lived experience to the policy sector. We provide skillbuilding, knowledge-building, a platform, and autonomy to the PEs to allow them to drive policy change through research, policy development, and advocacy, informed by their communities. We work on the issues our PEs identify, including education, climate change, criminal justice, immigration, economic opportunity, national service, and housing and design.

Next100’s ongoing work to support PEs in driving policy change and engaging directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development has revealed a real demand among directly impacted communities for opportunities to meaningfully participate in the policymaking process. However, we have also learned that the opportunities for directly impacted communities to significantly influence and impact public policy are rare. We believe the scarcity of those opportunities is in part a reflection of a broader systemic effort to exclude communities and individuals from public policy, but is also due to a genuine lack of understanding among policy sector organizations on how to best engage directly impacted communities. The recommendations and strategies that inform this toolkit are a distillation of the insights and lessons learned from doing the critical work that is Next100’s mission.

Who is this toolkit for?

If you work at an organization that aims to research, develop, influence, enact and/or implement public policy, this toolkit is for you—whether you work in an early career or leadership position, whether you work in policy, research, or advocacy. Everyone in these fields has a role to play in improving engagement with, learning from, and empowerment of directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development.

When discussing the “policy sector” as the audience for this toolkit, we are including nongovernmental organizations that seek to influence policy, such as think tanks, policy research and advocacy organizations, and others; as well as all levels and branches of government. We understand each of these organizations faces different challenges and opportunities in implementing some of these practices; but overall, we believe that across the sector, there are substantial opportunities for improvement.

What’s in this toolkit?

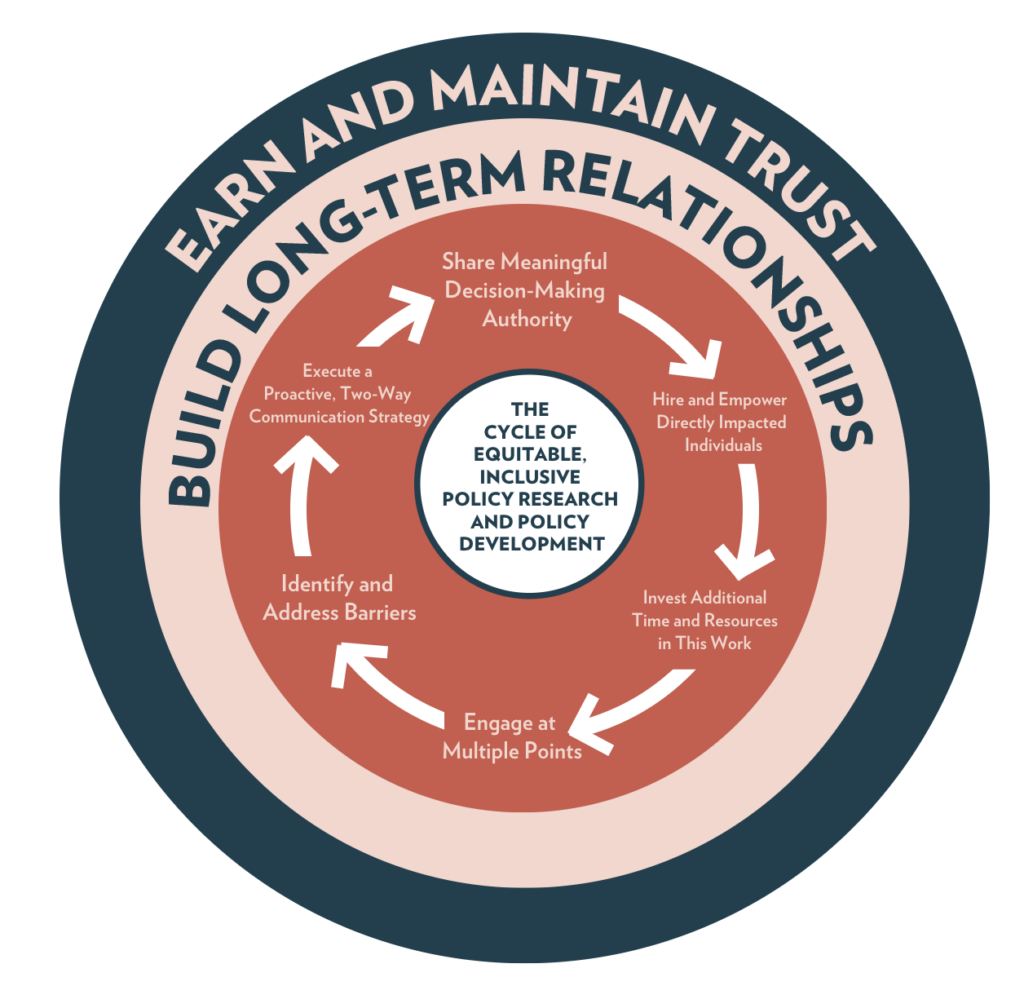

FIGURE 1

This toolkit presents a series of strategies to enhance inclusion, collaboration, empowerment, and equity in policy research and policy development, by helping policy sector organizations engage with directly impacted communities. Our recommendations include:

- Earn and Maintain Trust. Trust is the foundational structure that will help policy sector organizations create and sustain long-term relationships with impacted communities and individuals that allow those communities and individuals to feel empowered and engage honestly and productively in policy work. It’s a necessary—but not sufficient—building block that must be established and maintained between the policy sector and impacted communities.

- Build Long-Term Relationships. Proactively identify which individuals and/or communities should be an ongoing part of policy research and policy development and engage with those individuals and/or communities, ideally for long-term collaboration and partnership across multiple projects and goals.

- Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority. Identify opportunities to collaborate with and empower directly impacted individuals and communities by encouraging them to exercise their autonomy and self-determination at various stages of the policymaking process.

- Hire and Empower Directly Impacted Individuals. Ensure that your organization employs directly impacted individuals in full-time roles and as contractors to lead the policymaking process.

- Invest Additional Time and Resources in This Work. Invest the time, funds, and people—including from directly impacted communities themselves—that are necessary for equitable and inclusive engagement and empowerment.

- Engage at Multiple Points. Directly impacted individuals should be engaged at the start of, and throughout, the policy research and policy development process.

- Identify and Address Barriers. Proactively identify the practical and strategic challenges that impede the participation of directly impacted individuals and engage directly impacted communities to solve for them.

- Execute a Proactive, Two-Way Communication Strategy. Practice active listening, provide opportunities for gathering input and sharing feedback, and deliver key messages as early as possible using language and modalities that are accessible to everyone.

The toolkit also includes several examples of how these strategies have been used when policymakers engage directly impacted communities.

Recommendations

and

Maintain Trust

Recommendation 1.

Earn and Maintain Trust

Earn and maintain trust with directly impacted communities and individuals.

Trust, while difficult to establish, is the foundational structure that will help policy sector organizations build and sustain long-term relationships with impacted communities and individuals that empowers them to engage honestly and productively in policy work. It’s a necessary—but not sufficient—building block that is critical to each additional recommendation in this toolkit. Building trust is not easy, especially at first. Policy sector organizations can establish trust by demonstrating respect for the expertise of impacted communities, being transparent and forthright with communication, and avoiding transactional or tokenizing interactions.

The importance of trust when engaging directly impacted communities cannot be overstated. However, a longstanding legacy of exclusion means impacted communities are rightfully skeptical of the government, public policy, and the policy sector more broadly. Where decades or centuries of exclusion hurts, inclusion can help: emerging research demonstrates that feelings of belonging can act as a predictor of political interest and engagement among Latinx individuals. In a survey Next100 conducted in partnership with GenForward in winter 2021, we found plenty of evidence of a disconnect between young adults and government, especially among young adults from historically excluded communities. For example, the data revealed low levels of trust in federal, state, and local governments among young adults. The data also showed that Black respondents and respondents with a household income of less than $30,000 were twice as likely to disagree that they felt like, “full and equal citizens” than white respondents and respondents with a household income of $100,000 and higher. Unfortunately, the feelings of disconnection and skepticism were reflected in respondents’ divergent beliefs and perceptions in their ability to drive change in their communities and, consequently, engagement and plans to engage in methods for making change. While these poll findings can feel daunting, there was also a silver lining: an overwhelming majority of young adults reported they are more likely to trust government leaders, when they come from their community. This final insight points toward an opportunity for the public policy sector to have a substantive impact in restoring the faith in our democracy and government through engagement and bridge building with directly impacted communities. Foundational to that work will be repairing and improving the trust between directly impacted communities and the policy sector.

A longstanding legacy of exclusion means impacted communities are rightfully skeptical of the government, public policy, and the policy sector more broadly.

While the work of developing and/or restoring trust may feel intangible, this toolkit presents some concrete approaches that can be used to establish and maintain trust with directly impacted communities. Each of the approaches listed below are expanded on further in the recommendations and strategies presented in this toolkit.

- Engage and build long-term relationships with directly impacted individuals and the community-based organizations (CBOs) that have trusted relationships with, and are proximate to, directly impacted communities (see Build Long-Term Relationships).

- Recognize that communities are complex and include a diversity of individuals, perspectives, and opinions; no one should be asked to speak for an entire community (see Build Long-Term Relationships).

- Share meaningful decision-making authority (see Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority).

- Recruit, hire, equip, and empower directly impacted individuals to lead policy work (see Hire and Empower Directly Impacted Individuals).

- Allocate the additional time and resources needed to equitably engage with impacted communities and demonstrate that you value their experiences and participation (see Invest Additional Time and Resources in This Work).

- Pay people fairly for their time, insights, and expertise (see Invest Additional Time and Resources in this Work).

- Engage with directly impacted individuals and communities at multiple points in the process, and beyond (see Engage at Multiple Points).

- Identify and address barriers to participation for impacted individuals (see Identify and Address Barriers).

- Leverage a proactive, two-way communication strategy at each stage of the process and in multiple languages and modalities (see Execute a Proactive, Two-Way Communication Strategy).

SPOTLIGHT Engage and build long-term, trusting relationships with directly impacted communities

“[The] objective was not to make a policy, the objective was to be in long-term relationship with people. And then the policy solutions and the program solutions that came out of that were far greater and more diverse, than if we started with, ‘We have to solve a problem, so let’s find a group of people and backfill a solution that we already created.’”

—Jason Starr, former assistant counsel to the governor in New York State

In 2018, Jason Starr was the assistant counsel to the governor in New York State and the governor’s lead counsel on housing issues. When developers in Rochester were planning to tear down the Cadillac Hotel—a local homeless shelter of last resort—the local response by people experiencing homelessness and their allies created a political crisis for Governor Cuomo’s administration. Jason was asked to step in, and identified a three-tiered mission: to address the immediate crisis, to better understand the root cause of housing insecurity in Rochester from people who were experiencing it to inform future policymaking, and to build relationships with impacted individuals to inform policymaker discussions.

Since Jason did not have the proper pre-existing relationships in Rochester, he began by asking local contacts and housing affordability advocates who were the right people to connect with. After identifying the direct service providers and activists he should connect with, he set out to build trusting relationships with them. Jason recognized that, as a government official, he carried baggage into these interactions, and that directly impacted communities had real and longstanding concerns with the government—both of which made building trust more difficult. In an effort to build trust with individuals who were housing insecure, Jason decided to meet them in a location that would be more familiar and comfortable to them: in the shelter. Jason not only visited the shelter, he spent a night there and fulfilled the community requirements for an overnight stay—which included helping to set up the shelter, cook dinner, and clean—all of which helped him connect with directly impacted individuals in an organic and authentic way that led to mutual understanding and trust.

In addition to connecting with directly impacted individuals, Jason also made an effort to ensure they knew that they—and their perspectives—were valued. Jason accomplished this by demonstrating humility and approaching each engagement as an “opportunity to learn.” He also recognized the need to act in mutual aid and reciprocity with the community—that is, he couldn’t simply be there to extract wisdom from them, he needed to also prioritize their needs and offer something in return. Jason maintained an ongoing relationship with directly impacted individuals beyond his stay at the shelter and proceeded to hold meetings with the individuals he connected with in Rochester and policymakers and decision makers in the executive chamber who had authority over housing issues—not just as part of the immediate crisis, but as an ongoing practice.

Long-Term

Relationships

Recommendation 2.

Build Long-Term Relationships

Identify and build long-term relationships with the individuals and communities who should be engaged in policy research and policy development.

Proactively identify which individuals and/or communities should be an ongoing part of policy research and policy development and engage with those individuals and/or communities, ideally for long-term collaboration and partnership across multiple projects and goals.

Strategy 1. Identify which individuals and/or communities need to be at the table to build an inclusive policy research or policy development project.

There are many factors that can be used to help policy sector organizations identify the directly impacted individuals and/or communities who need to be included in policy development work. At base, a policy sector organization should use what they already know about the issue area, the policy intervention they are considering (if any), and the demographic data on disparities concerning the issue area to identify some of the critical individuals and communities to engage.

For example, if a policy sector organization is working to improve economic justice, then it may make sense to engage with individuals who are impacted by underemployment or unemployment to create a workforce development policy that meets their needs. Thus, both the issue area focus (economic justice) and possible policy intervention (workforce development policy) can help narrow the field of who should be included in the policy development work.

Data that examines disparities, including racial and ethinic disparities, and includes consideration of the geographic (local/state/national) context for the policy intervention can also be used to identify the individuals and/or communities who should be included in the policy development process. In the economic opportunity example, national data demonstrate clear labor force disparities by racial and ethnic background, thus, policy sector organizations may want to focus on the communities of color impacted by these disparities. However, that focus may only make sense if the policy development is happening at the national level, and may require the use of more granular data and a focus on individuals with different racial or ethnic backgrounds for state or local policy development.

Furthermore, while race, ethnicity, and gender are often reliable social determinants for experiencing a variety of challenges, they should by no means be understood as the only lenses available to examine who needs to be included in policy development work. For a variety of reasons, many of which are driven by policy, data shows that there are certain populations—immigrants, people with disabilities, people experiencing homelessness, LGBTQ youth, young adults, and seniors—who may be differentially impacted, positively or negatively, by policy decisions pertaining to economic justice or other areas. Where the negative differential impact is known, engaging those populations may be critical.

Ultimately, policy sector organizations may want or need to engage with just one of these populations, with each of them, or with an intersectional cross-section of just a few. Whatever the case may be, policy sector organizations should be proactive about identifying key individuals or groups up front to inform the work from the start.

“When you bring in people who are new to the policy sector, it disrupts how we traditionally describe success. I’m asking leaders to lean into a learner’s mode – to imagine what’s possible. It can cause some cognitive dissonance because I am asking people to be a learner rather than an expert, in a field where expertise is highly valued.”

—Tamara Osivwemu, managing partner, The Management Center and racial equity consultant

Strategy 2. Engage and build long-term relationships with directly impacted individuals and the community-based organizations (CBOs) that have trusted relationships with and are proximate to directly impacted communities.

Once policy sector organizations identify which individuals and/or communities need to be included at the policymaking table, for an individual project or the long-term, the next step is finding the individuals who can engage in the work and, ideally, establishing trusting, long-term relationships with them (for more on the importance of trust, see Earn and Maintain Trust). Policy sector organizations should look to connect with the existing social networks of directly impacted communities and identify the specific individuals who have an interest and the capacity to be involved in policy research and policy development.

CBOs that are situated within impacted communities, led by individuals from those communities, and working daily to support and empower those communities can be effective conduits to reaching directly impacted communities. However, if CBOs (or individuals!) are only pulled in during moments of need, it can erode trust and their ability and desire to engage effectively in the work. As such, policy sector organizations should prioritize developing trusting, long-term relationships with CBOs and individuals, that allow for two-way engagement and ongoing work together.

If community-based organizations (or individuals!) are only pulled in during moments of need, it can erode trust and their ability and desire to engage effectively in the work.

In addition, it is important for policy sector organizations to understand there can also be limitations to only working through existing organizations and their employees. Even the most trusted CBO has limited reach and appeal to directly impacted individuals. As such, if policy sector organizations exclusively rely on CBOs to connect with directly impacted individuals, they may inadvertently overlook the perspectives and opinions of people who do not have relationships with CBOs and who may have different experiences or needs. Policy sector organizations can rely on a diverse cross-section of multiple CBOs—including faith-based, direct-service, and recreational organizations—to expand their reach and mitigate the risk of overlooking people who may not have close relationships with one specific organization. They should not limit their outreach and relationships to organizations that do policy and advocacy work. In addition, once policy sector organizations have established their own trusting relationships with individual community members, in a way that community members perceive as respectful and valuable, those community members may connect them to people in the broader community that may not have a relationship with local CBOs.

As noted above, policy sector organizations should prioritize long-term relationships with directly impacted communities, which includes maintaining relationships beyond the end of a specific policy research or policy development project. There are a number of practical reasons for doing so. Maintaining long-term relationships with directly impacted communities leaves the door open for future collaboration: to drive policy change on an existing policy priority (since policy change can often be slow moving), to continue the collaboration through policy implementation (should the desired policy change happen), to stay proximate with evolving community needs and knowledge (since it can inform additional work or change policy priorities), or to focus on another policy priority (since many individuals experience cross-cutting social inequities). Most importantly, long-term relationships are critical to maintaining trust and credibility with communities, especially with directly impacted individuals who have experienced the status quo (short-term and extractive) dynamics of collaboration with the policy sector.

To maintain long-term relationships, policy sector organizations should consider having regular check-ins with communities and continue to share opportunities to participate in policy research and policy development, including opportunities that would allow individuals to amplify their voice, such as speaking on panels or with the media. The timing of check-ins (such as monthly, bi-monthly, quarterly, and so on) is not as important as ensuring there is consistency. The check-ins can also take on a number of different forms (emails, phone/video calls, in-person meetings, and so on) and can be formal or informal. Policy sector organizations should seek input and feedback from directly impacted communities on the frequency of check-ins, as well as the substance and structure.

Strategy 3. Recognize that communities are complex and include a diversity of individuals, perspectives, and opinions; no one should be asked to speak for an entire community.

Directly impacted communities are not a monolith and differences in experiences (in terms of education, socioeconomic status, language, values, and so on) may lead to differences in opinions. Policy sector organizations must be aware of and try to navigate these differences. Policy sector organizations should avoid leaning into confirmation bias by elevating or favoring the opinions that are most aligned with their own thinking. Furthermore, policy sector organizations should not ask individuals to speak or represent their entire community. Either of these approaches will serve to only tokenize—make their participation merely a symbolic gesture—individuals.

Decision-Making

Authority

Recommendation 3.

Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority

Identify opportunities to collaborate with and empower directly impacted individuals and communities by sharing authority over direction and decisions at various stages in policy research and policy development.

It is critical that the policy sector reconsider the assumptions that lead to the exclusion of directly impacted communities from decision-making and examine when and where to expand their influence and authority in policy research and policy development. Failing to do so will only continue to undermine the relationships and trust between communities and the broader policy sector. This toolkit and its recommendations are all predicated on the idea that directly impacted individuals are untapped leaders and experts in policy research and policy development and that their unique insights and experiences can, and should, be used to identify policy priorities and lead policy change. That empowerment cannot happen if they are denied the opportunity and ability to make decisions about the public policies that impact their lives.

Strategy 1. Identify the scope and degree of community influence and input and ensure that directly impacted communities are exercising the decision-making authority that aligns with those goals.

Too often, policy sector organizations engage with directly impacted communities in a manner that can feel like window dressing—light-touch engagement in which the hardest substantive and strategic questions are not addressed. This type of engagement can be the direct result of practical—time, resource, capacity, or scope—limitations to the work; these situations require transparency and clear communication to manage expectations and preserve trust (see Execute a Proactive Two-Way Communication Strategy). However, when practical limitations are not an impediment, policy sector organizations can, and should, question whether directly impacted communities are being asked to meaningfully engage in decision-making and make consequential decisions, or at the very least have a strong influence over those decisions. Otherwise, directly impacted communities are simply being asked to be spectators and bear witness to the historical, ongoing, and systemic exclusion that has dominated the policy space. This devalues their lived experience and wisdom, relegating them to secondary considerations.

The International Association for Public Participation’s spectrum of public participation framework is a helpful tool that can help policy sector organizations assess the goals of community participation and the corresponding level of authority and decision-making that the community should expect with that goal (see Figure 2). The framework operationalizes the potential goals of participation into a continuum: from informing, to consulting, to involving, to collaborating, and, finally, to empowering. The influence and decision-making authority of directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development increases as the goal of participation moves from infoming to empowering. The role of directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development may differ throughout each stage of the same project. Thus, policy sector organizations should consider the use of the framework as an ongoing and dynamic exercise that requires regular assessment before each decision-making juncture.

Figure 2

Strategy 2. For large projects and formal partnerships, co-develop a structure for the partnership between policy sector organizations and directly impacted communities, including an oversight committee with decision-making authority to ensure an equitable distribution of power.

Policy sector organizations and directly impacted communities should co-develop and adopt practices and norms that foster belonging, equitable inclusion, and shared planning and decision-making in their partnership. Ideally, these steps should be taken at the early stages of the partnership. Partners should co-create and adopt group agreements that will facilitate full participation, including decision-making, for everyone. This may require decentralizing decision-making in the partnership by creating advisory groups and committees. In addition, policy sector organizations can establish an accountability group with independent authority to monitor the partnership and elevate the voices of impacted communities to ensure that their perspectives and preferences are adequately incorporated into the policy work.

Directly Impacted

Individuals

Recommendation 4.

Hire and Empower Directly Impacted Individuals

Recruit, hire, equip, and empower directly impacted individuals to lead policy work.

Ensure that your organization employs directly impacted individuals in full-time roles and as contractors to lead policy research and policy development.

The strategies in this toolkit can be used to engage impacted individuals and communities in the policy development process. In addition, policy sector organizations can work to hire directly impacted individuals into organizational roles that influence and drive policy and research, and support and empower them to drive this work. Despite how necessary lived experience is to inform effective policy development, prioritization, and implementation, policy sector staff are rarely representative of the people whom their decisions most impact. Hiring directly impacted individuals to drive policy work is an important step in ensuring lived experience is included at each stage of that work, and can also help improve an organization’s ability to effectively implement many of the strategies in this toolkit, from building trusting relationships with CBOs to creating effective outreach and communication plans.

Hiring directly impacted individuals to drive policy work is an important step in ensuring lived experience is included at each stage of that work, and can also help improve an organization’s ability to effectively implement many of the strategies in this toolkit.

Strategy 1. Hire directly impacted individuals for full-time roles within the policy sector.

Policymakers are too often not representative of the people whom their decisions most impact. In the United States, 42 percent of the population identify as people of color, and the diversity of the country is only growing: more than half of the country’s youth identify as people of color. Meanwhile, the country’s policymakers do not reflect this diversity, with less than one in four Congressional members identifying as people of color and only 9 percent of U.S. Senator’s chief of staff were people of color (see Figure 3). Because of this, agenda-setters and their communities are less likely to have direct experience with the consequences of their policy choices and how policy and program implementation works in practice. Overall, they may be less likely to have directly impacted individuals in their personal and professional networks. Consequently, the priorities of policymakers are less likely to align with those of impacted communities. Having policymakers who are from and intimately connected to impacted communities influences the policies they develop, research, enact, and implement—and can help improve the execution of many of the strategies in this toolkit.

Figure 3

In 2020:

42% of the U.S. population were people of color. 42% of the U.S. population were people of color. |

53% of young people were people of color. 53% of young people were people of color. |

22% of members of Congress were people of color. 22% of members of Congress were people of color. |

9% of U.S. Senators’ Chiefs of staff were people of color. 9% of U.S. Senators’ Chiefs of staff were people of color. |

|---|

And yet, while hiring and empowering more impacted individuals to drive policy change is an effective tool to improve public policy, a series of existing intentional and unintentional barriers make it more challenging for individuals from these historically excluded groups to break into policy sector roles. Next100 previously developed a toolkit of concrete actions policy sector organizations can take to address this historical exclusion, and build more inclusive policy sector organizations: “Building a More Diverse, Inclusive and Effective Policy Sector: A Toolkit for Think Tanks, Policy Nonprofits, and Governments.”

Strategy 2. Hire contractors—such as advisors, contributors, facilitators, and organizers—from directly impacted communities.

In the long run, the policy sector will be stronger if far more directly impacted individuals are employed by and driving policy change within the sector. In the short run, and to widen pathways and interest for impacted individuals to engage in policy work, policy sector organizations can expand their capacity and effectiveness by hiring individuals from directly impacted communities as contractors. Organizations can hire individuals to both facilitate the work with communities, to develop their own policy work and contributions, and, where needed, to build the knowledge and skills needed by directly impacted communities to fully engage and exercise informed leadership within policy research and policy development. Contractors should be paid a livable, fair wage, consistent with the value that they bring to the work.

Time and Resources

in This Work

Recommendation 5.

Invest Additional Time and Resources in This Work

Allocate the additional time and resources necessary to engage with impacted communities and value their experiences and participation.

Invest the time, the funds, and in the people—including from directly impacted communities themselves—that are necessary for equitable and inclusive engagement and empowerment.

It will take time and effort to include directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development, especially if the aim is to have them lead and influence the conversation at each stage, not just participate in it. Therefore, policy sector organizations need to invest adequately in the time, resources, and people that will lead to success.

Strategy 1. Build in time for an equitable and inclusive process.

This toolkit outlines a number of explicit steps policy sector organizations should take to make policy research and policy development more equitable and inclusive. To paraphrase a well-known adage: the policy sector can go fast (and alone); or it can go far (together, with directly impacted communities). With additional people involved, policy research and policy development will require more time. Speeding through the process risks undermining the trust and the agency of directly impacted individuals; and as is frequently the case, makes it more likely that the policy sector will develop policy that excludes impacted communities, or does not serve them well. The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) is a recent example of how a rapid response policy can exacerbate existing inequities. Due to historically discriminatory practices, communities of color often face challenges in capital access. When large banks were used as intermediaries to move PPP funds to small businesses, the lack of pre-existing banking relationships for business owners of color proved to be a barrier to accessing PPP funds.

Some of the recommendations and strategies in this toolkit will need more time. Listening sessions (see Execute a Proactive Two-Way Communication Strategy), identifying and addressing barriers to participation (see Identify and Address Barriers), developing shared priorities and goals (see Engage at Multiple Points), and making collective, as opposed to unilateral, decisions (see Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority), will take longer to complete compared to the status quo. At the beginning of a policy research or policy development project, policy sector organizations should plan for the additional time needed to execute on these strategies, taking into account that many directly impacted individuals have not organized their daily lives and schedules around policymaking and thus will have competing priorities—such as their jobs, child care, or other caregiving responsibilities, and other obligations—and that among these, policy work (understandably) may not be their highest priority. Policy sector organizations should build timelines that are respectful of everyone’s competing responsibilities at each stage of the process.

“There are certain things you want to put in place [for successful engagement with directly impacted communities]… conversations that make space for community members to take in another direction. Even if it was supposed to be about some topic in particular. [Policy sector organizations should also demonstrate] lived experience has value and pay people for their time, to sit on panels, to share their thoughts.”

—Khalilah M. Harris, formerly with Center for American Progress

Strategy 2. Budget and fundraise to effectively partner with directly impacted communities, and ensure those communities’ time and expertise is valued.

Generally speaking, a longer timeline means the process will also be more costly, and involving more impacted individuals and paying them for their time and expertise will take additional resources (see Build Long-Term Relationships). In addition, funds will be needed to provide training, skill building workshops, professional development, and continuing education for policy sector organization staff and impacted communities. Policy sector organizations will also need additional staff capacity to engage directly impacted communities more equitably, especially organizations that are not already well equipped with the skill sets necessary to successfully execute equitable partnerships with directly impacted communities.

As outlined above, embracing the strategies and practices in this toolkit will require additional funds. Among other things, policy sector organizations should plan and budget for funding that will allow them to address the barriers (transportation, and so on) that impede the participation of directly impacted individuals and also pay individuals for contributing their time and expertise.

To fill these funding needs, policy sector organizations should evaluate their internal budget priorities and reflect on whether they can make different choices to establish and maintain better working partnerships with directly impacted communities. Even if these adjustments are made, it is very likely that many nongovernmental organizations will also have to fundraise to implement the strategies recommended in this toolkit. Organizations should build these activities into organizational budgets and grants, and make the case for them directly to funders. Fortunately, many funders are slowly, but surely, acknowledging the need for more inclusive processes across issue areas. Policy sector organizations should seek and advocate for grants that prioritize the engagement of directly impacted individuals, which will require being credible messengers for the value-add and impact of a new approach.

“We firmly believe in compensating young people for their expertise, emotional labor, time, etc. For example, to serve on a panel discussion, we pay at least $150–$200 per hour. Additionally, our Executive Committee on our Youth Advisory Board receives a stipend to honor their time and commitment to our organization. It is important to not be extractive in youth work, and to work alongside young people to identify how to best honor their time, whether it is providing compensation, a networking connection, or some other opportunity.”

—Nikki Pitre, Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute

Strategy 3. Pay people fairly for their time, insights, and expertise.

Time is a precious resource that is impossible to replace; and lived experience should be valued like other forms of expertise. Policy sector organizations should adequately pay directly impacted individuals for dedicating some of their limited time to policy work—both to demonstrate an appreciation to individuals for sharing their expertise and to minimize the opportunity costs that some individuals may face from missing work to participate. Paying directly impacted individuals signals to them—and the broader policy sector—that the time, labor, insight, and wisdom they bring to the policy work is valued.

Pay should be provided in a form that will be easy for all to access without taking on additional expenses—for example, through gift cards—and at a rate that demonstrates clear value to participants. Policy sector organizations should ensure funds are available for these costs by being proactive about building these costs into project budgets and philanthropic grants.

A Note on Philanthropy

Embracing the recommendations in this toolkit will require an investment of an organization’s time, energy, and funding. From creating a comprehensive communication and outreach strategy to addressing the barriers that impede the participation of directly impacted communities, effective, inclusive policy research and policy development with communities will take resources.

This is an opportunity for organizations to interrogate internal budget priorities and reflect on whether their budget choices live up to the equitable values and promise of their missions.

But funding choices in the policy sector extend to the funders that provide vital support to nongovernmental policy organizations. Since the majority of revenue for these organizations comes from individual and institutional funders, funders’ willingness—or lack thereof—to provide adequate funds and appropriate time horizons for deliverables developed through an inclusive process can be a central part of the challenge.

While there is no doubt that many funders are increasing their support for directly impacted communities in their grant opportunities, these investments are largely concentrated in activities that directly impacted communities are already most likely to be included in, such as organizing and advocacy; and the funds often fall short of reflecting the meaningful value lived experience brings to the policymaking table. In this way, philanthropy tends to perpetuate the limited, light-touch engagement with communities that already exists in parts of the policy sector.

As outlined in this toolkit, the role of directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development can and should be expanded to include different stages in the process: setting priorities; defining the scope and root causes of the problem; generating innovative policy solutions; and executing effective implementation. Moreover, individuals should be fairly compensated for their time. Funders can and should ask organizations about how they are expanding the role of directly impacted communities—and encourage open conversation about what different strategies can be used to engage directly impacted communities and what is needed, from a resources perspective, to build and maintain the long-term relationships outlined in this toolkit. Furthermore, it’s essential that philanthropy support organizations not just with the funding, but with the grant timelines that would allow for the equitable inclusion of directly impacted communities. In turn, nongovernmental policy organizations must collectively make the case—both through internal budgetary decisions and to funders—that the additional resources needed to make this process accessible for all communities is worth prioritization and increased investment by philanthropy.

at Multiple

Points

Recommendation 6.

Engage at Multiple Points

Engage with directly impacted individuals and communities at multiple points in the process, and beyond.

Directly impacted individuals should be engaged at the start of, and throughout, the policy research and policy development process.

Too often, policy organizations, from governments to think tanks, will include impacted communities in policy research and policy development when policy ideas are already fairly developed and hard to change, or simply pull communities in for the advocacy stage (when it’s time to meet with elected officials, hold rallies, or participate in other methods for driving change). Policy sector organizations should pivot away from this narrow engagement with directly impacted communities to one that is more comprehensive. For example, directly impacted communities should be involved in setting an agenda and priorities, developing a vision and goals, identifying policy solutions, informing a strategy to drive policy change, and implementing policy solutions. At the minimum, impacted communities should be able to have influence in each of these steps. However, whenever and wherever possible, the goal should also be for the preferences of directly impacted communities to be sincerely and significantly reflected in each step of the process and in the final product (see Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority). This shift will require engaging directly impacted communities at the beginning of the process and equipping them with the knowledge to prioritize and drive their own solutions. Furthermore, relationships need not end, just because a project has.

Strategy 1. Include directly impacted communities at the beginning of the process.

Communities too often are engaged by the policy sector only in a limited capacity—to identify problems, react to advanced policy proposals that are not likely to be changed, or engage in advocacy—but are not included in other phases of the work. At Next100, we have developed a “making policy change” framework to anchor our training and help us navigate not only how to think about policy problems, solutions, and change-making strategies, but also how to ensure impacted communities are included in critical stages of the policy change process (see Figure 4). The framework breaks down the process of making policy change into five steps—(1) vision, (2) problem, (3) solution, (4) decision-maker(s), and (5) change-making strategy.

Policy sector organizations can engage directly impacted communities by holding listening sessions that co-develop a vision, and/or co-identify problems and policy solutions. This process can help ground the policy work in what matters most to directly impacted communities. To facilitate these conversations and identify community priorities, policy sector organizations should ask open-ended questions that are not biased and avoid leading the work to a preconceived end point. However, even if policy sector organizations are asking the right types of questions, individuals from directly impacted communities must also feel comfortable to express their opinions. This is why it’s important that policy sector organizations demonstrate they are listening to and learning from the input and feedback that occurs through these sessions.

Figure 4

Strategy 2. Continue to engage directly impacted communities throughout the entirety of the policy research and policy development process.

It may be obvious, but it is still worth reinforcing that the importance of engagement does not diminish as the work progresses. The practice should continue throughout the entirety of the process; the perspectives of directly impacted communities should be included in an ongoing way and not just in limited circumstances. In addition, policy sector organizations should solicit input and feedback on steps in the process where they may not traditionally seek them. For example, policy sector organizations can solicit input on which problems to prioritize, on the policy ideas themselves, on a draft of recommendations, or on a draft report before publication (ensuring in all cases to demonstrate respect for people’s time and labor by providing an ample time for input and paying individuals for their work; see Invest Additional Time and Resources in This Work). In short, the wisdom of directly impacted communities should be leveraged to inform as much policy research and/or policy development as possible—including implementation. Regular and ongoing engagement with directly impacted communities will ensure policy work reflects and iterates on the insight that communities share with policy sector organizations.

“Some of this is a people challenge. Many in the policy sector don’t share the opinion that people closest to the issue are experts. Shifting the mindset of people is the challenge. ‘Yes, you are an economist, but you don’t understand how your suggestion impacts people day to day. Without that story your supposed expertise is limited.’ There is a history of predation with how some researchers engage communities that does not necessarily lift up the actual experiences of people… There are people in the policy space who are not familiar with this approach. That will take longer and their pushback is they would like [the policy research and policy development] to go faster.”

—Khalilah M. Harris, formerly with Center for American Progress

SPOTLIGHT Engage directly impacted individuals and communities throughout the policy research and policy development process

“If you want to say that you are actively including [directly impacted communities] in policy solutions and policy recommendations, it doesn’t happen by just listening to them one time. Do you then go back to them and share what you heard? Do you ask them ‘What do you think about these solutions? What do you think about these recommendations? Do they reflect what you’d want for yourself? What’s missing? How can we make it stronger? What can make it better?’”

—Rosario Quiroz Villareal, Next100 alumna policy entrepreneur

In 2021, Rosario Quiroz Villareal, a former policy entreprenuer at Next100, partnered with ImmSchools and the Haitian Bridge Alliance to release Embracing Our Strength, an immigrant-designed and immigrant-led project to develop and identify state-level policy recommendations to address the needs of undocumented and mixed-status immigrant families.Early on, Rosario knew she wanted to push against the dominant immigrant narratives that excluded Black immigrants. In order to ensure that both Black and Latinx immigrant communities were informing the work, Rosario identified two direct service organizations—ImmSchools and Haitian Bridge Alliance—who were trusted by, and had strong connections to, directly impacted communities, as partners for the project. ImmSchools and Haitain Bridge Alliance each identified immigrant parents in mixed-status and undocumented families in California, Florida, New York, and Texas with whom they had pre-existing relationships, and trust. Both organizations were willing to do this because they were partners in the project, and believed it had value for their communities.Next100, ImmSchools, and Haitian Bridge Alliance crafted a series of structured conversations, or focus groups, to learn from the parents about their experiences and visions. To make sure parents were able to participate, the focus groups were held in parents’ primary language (Spanish or Haitian Creole), and time was built in to gather feedback and input from the participants. In addition, parents were paid for their participation—as a way to acknowledge the value they brought to the process and demonstrate appreciation for the time parents invested in it too.Next100, ImmSchools, and Haitain Bridge Alliance were intentional about ensuring parents themselves were co-creating the policy agenda, and engaged at each step along the way—not just at the end. At the beginning of the focus groups parents were asked two simple yet aspirational questions: “‘What are the dreams you have for yourself? What are the dreams you have for your children?’” These questions did not use policy jargon or language that would otherwise be inaccessible to parents. Rather they were rooted in the hopes that any parent would have for their family’s future. Those questions, along with other open-ended accessible questions that would inform the rest of the work, positioned parents as experts, which was critical to the process.

Being formerly undocumented herself, Rosario understood that the conversations stemming from the focus groups could trigger trauma and emotional distress for parents. She prepared a list of state-specific and culturally appropriate resources that could offer mental health support for undocumented and mixed-status families. Recognizing that generational differences meant that some parents would not feel comfortable accessing mental health services, she and her partners also included social well-being practices and resources that would appeal to a broad spectrum of parents.

The parent participants were engaged again at the recommendations stage. The organizations summarized their findings and recommendations into a presentation for the parents to ensure that: (1) the perspectives of parents were accurately reflected in her work; and (2) that the recommendations were consistent with the policy change they hoped to see. Feedback from the parents, Rosario said, “helped strengthen the work; it really showed the gaps and blindspots within my own analysis and that’s where there is real power in collaborating with real people, who maybe are similar in some ways, but still hold different experiences.”

When the report was finally released, it included an executive summary that was available in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole. The summary was focused on the findings and recommendations—the key elements that would be shared with policymakers, would also be available for directly impacted communities.

“Our practitioner-informed approach means that the experiences of participants and staff are truly shaping our policy recommendations and that their stories are heard and centered. In order to realize this, we’re developing mechanisms to facilitate regular, frequent communication between Osborne’s Policy Center and program staff to learn about participants’ challenges and successes, and systemic barriers. We try to have people with lived experience physically present in all training and technical assistance spaces, and at minimum we include video of their experiences to ensure their voices are in the forefront. We have an Advisory Board composed of folks who are directly affected by the criminal legal system who may not want to speak publicly, but can offer input on policy, messaging, and more.”

—Allison Hollihan, Osborne Association

and

Address Barriers

Recommendation 7.

Identify and Address Barriers

Identify and address barriers to participation for impacted individuals.

Proactively identify the practical and strategic challenges that impede participation by directly impacted individuals and engage individuals impacted by those challenges to solve for them.

Even well-intentioned efforts to include directly impacted communities can run into challenges. Policy sector organizations should be proactive about identifying and addressing the various practical and strategic challenges, such as a lack of trust in government and competing views on the root causes of a problem, that may limit an individual’s ability to fully participate. Moreover, depending on an individual’s circumstances, they may also face steeper opportunity costs in participating due to their employment or challenges meeting their basic needs (housing, food, clothing, transportation, and so on). This is why it’s essential to identify and address the practical and strategic challenges to participation.

Strategy 1. Anticipate common practical barriers to participation, such as transportation and technological barriers, and have a plan to address them.

There are multiple barriers that members of impacted communities may face when organizations ask them to participate in policy work. Removing these barriers is necessary to ensure participation by these individuals. Eliminating these barriers is not complicated work, but will take intentional planning and investment of time and resources. Common challenges participants face can include:

- Time: People are busy with their own lives. Organizations should be respectful of and efficient with participants’ time.

- Schedule: Individuals who are working one or more jobs may not have flexibility to join sessions during the workday. Sessions should be scheduled at times that are maximally accessible to participants, even if that means evening or weekend times.

- Location: Physical location can be another impediment to participation. Ideally, meetings should occur where community members already congregate or, at the minimum, somewhere that is easily accessible to individuals, regardless of whether they have a personal vehicle or not. The costs of transportation (gas or public transportation fare) should be provided in advance, if possible; and if not, reimbursed. In addition, locations should be compliant with the accessibility requirements for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- Language accessibility: Policy sector organizations should be aware of communication barriers that can limit participation in the policymaking process. Organizations should use a broad range of outreach strategies, languages, and modalities to reach a wide audience for the work.

- Technology: Many impacted communities are adversely affected by the digital divide. Policy sector organizations looking to engage individuals who have limited access to the Internet and other digital communications technology should identify and address these challenges by providing the appropriate resources (tablets, hotspots, and other devices that provide access) that can help eliminate technological barriers to participation.

- Physical space and design: Policy sector organizations should also ensure that locations are welcoming and that individuals feel safe and comfortable in the spaces they are expected to work.

- Lack of food, child care, and other additional resources: policy sector organizations should look to provide food to individuals and their families, as involvement in policy research and policy development may limit a caregiver’s ability to prepare a meal. Food should be culturally appropriate (that is, considerate of food allergies, dietary restrictions, and cultural preferences). In the same vein, child care may also need to be provided.

Using Inclusive Design To Create Welcoming Spaces

Design is powerful; it can help influence whether or not directly impacted communities feel welcome in the policy space. Similar to the policy sector, decision-makers in the fields of architecture, real estate, and graphic design, are disproportionately white and male, which impacts what types of office spaces and websites are built. Policy sector organizations should acknowledge and address how directly impacted communities and individuals may feel when they enter these often highly surveilled spaces, which can feel exclusionary and could be uncomfortable, confusing to navigate, intimidating, and triggering. While redesigning an entire office space may not be within the budget, using community-engaged design practices can help to highlight specific design details that could act as either barriers or bridges to equity in the policy space. Design details such as culturally relevant, anti-racist artwork; clear, engaging, and translated signage; inclusive seating arrangements; and natural light and plants, as well as the provision of free menstrual hygiene products and lactation rooms, can work to build more equitable policy spaces. Thoughtful design, centering and valuing the knowledge of the people most impacted, can help us all move toward healing and justice.

Strategy 2. Anticipate common strategic challenges, such as a lack of trust for government, and have a plan to address them.

Strategic challenges are problems that may present themselves and require additional strategic thinking and engagement to resolve. Below are a few examples that we at Next100 have faced, and that other organizations may face when engaging directly impacted communities and individuals in policy work. These can include:

- Lack of trust: Directly impacted individuals may lack trust in the organization conducting the policy work, in the government, or in the policymaking process. This lack of trust is understandable, given the sometimes harmful actions of policy and government action and inaction and may manifest itself in disinterest or confrontational engagement with policy research and policy development. Policy sector organizations should be aware of the way lack of trust is manifesting and take actions to build and maintain trust (see Earn and Maintain Trust).

- Differences in experience and competing views: Differences in opinion may emerge, either within a directly impacted community or between the community and policy sector organizations. For example, differences in opinion may lead to some individuals feeling less comfortable speaking up or engaging than other peers. Policy sector organizations should be aware of these dynamics and address them. For example, if a policy sector organization believes a group of individuals is reluctant to participate due to differences in experiences of policy issues, organizations can provide additional opportunities to share those opinions and ensure all opinions are heard.

- Stigma: Directly impacted individuals may feel uncomfortable discussing sensitive topics (health and mental health, LGBTQ+ status, immigration status, reliance on social safety net programs, and so on) due to feeling unsafe or ostracized. In these situations, policy sector organizations should prioritize and maintain privacy and confidentiality with individuals and model healthy, respectful, and affirming interactions with the individuals who may feel stigmatized.

- Power dynamics: In all relational dynamics, each party has the ability to direct or influence the behavior of others. When policy sector organizations engage with directly impacted communities, there is usually a power imbalance because policy sector organizations are often able to set both the policy agenda and the terms for engagement. Policy sector organizations should be aware of these dynamics and look for ways to meaningfully share power with directly impacted communities (see Share Meaningful Decision-Making Authority).

- Urgency for change: Some directly impacted individuals may be eager for change, others may be more apprehensive about it. If the differences in urgency are not managed strategically, policy sector organizations may lose the interest and engagement of early adopters or leave behind individuals who need more time. Policy sector organizations should leverage ongoing engagement (see Build Long-Term Relationships and Engage at Multiple Points,) and communication strategies (see Execute a Proactive Two-Way Communication Strategy) to not lose the momentum or interest of either group.

In order to resolve these and other strategic challenges, policy sector organizations should be attentive, demonstrate a willingness to confront uncomfortable conversations, and be open to feedback and constructive criticism. Most importantly, the individuals directly affected by these challenges should be thought partners for collective problem solving.

There are also general approaches policy sector organizations can take to help tackle strategic challenges:

- Build trust with directly impacted communities to nurture the fortitude needed to navigate difficult situations together.

- Step back to see the different contexts surrounding a challenge. Reflect before stepping in to solve.

- Acknowledge the discomfort strategic challenges present. Everyone impacted by a strategic challenge feels a certain amount of tension or distress. Give people the time and space to process those feelings.

- Find common ground in values and a vision to guide conflicting interests and perspectives.

Strategy 3. Stay aware of emerging practical and strategic challenges.

It would be impossible to name all the practical and strategic challenges that policy sector organizations are sure to face while engaging directly impacted communities in policy research and policy development. The needs, contexts, and dynamics of communities are too unique for us—or anyone—to anticipate or explicitly name all these challenges. For that reason, policy sector organizations should proactively monitor and assess any emerging challenges they may need to address within the directly impacted communities they are working with, within their own or partner organizations, and/or across any of those relationships, preferably through two-way communication (see Execute a Proactive, Two-Way Communication Strategy).

Two-Way Communication

Strategy

Recommendation 8.

Execute a Proactive, Two-Way Communication Strategy

Leverage a proactive, two-way communication strategy at each stage of the process and in multiple languages and modalities.

Practice active listening, provide opportunities for gathering input and sharing feedback, and deliver key messages as early as possible using language and modalities that are accessible to everyone.

Communication is critical for all good partnerships and requires tailoring messages to meet partner needs, taking the time to receive input, and creating the conditions for honest feedback, reflection, and active listening. Effective communication is an important step that signals a commitment to equitable participation of directly impacted communities. At its best, communication can foster respect and empathy for all parties involved, both of which will help create trusting relationships. It can also create mutual understanding of partner strengths, values, norms, and cultures, which will make working together easier to navigate. Finally, communication will also help manage changes in process or goals, if they occur. On the other hand, poor communication practices can exacerbate trust challenges, disparities in power, and distance between impacted communities and policy organizations.

Beyond the benefits communication will have for relationships, it is also critical to policy work in more practical ways. A good communication strategy will improve the way policy sector organizations invite people to participate as well as the way directly impacted communities will learn of an opportunity to be involved in policy development. In addition, equitable partnerships with directly impacted communities require active listening to learn about the priorities, perspectives, and concerns of individuals with lived experience. Even as the work evolves beyond problem scoping and priority setting, effective communication will be necessary to keep directly impacted communities informed, so that they can exercise their autonomy and decision-making authority.

Strategy 1. Hold regular sessions with directly impacted communities that are based on active listening and proactive, transparent two-way communications.