The State of Housing and Employment for Asylum Seekers in New York

In this unique study, fifty New York City asylum seekers identify barriers to housing access and finding employment as key challenges to leaving shelter. The report offers three policy recommendations for state and city lawmakers to ameliorate housing resources and access to employment opportunities for asylum seekers.

When Roberto escaped captivity under the Bolivarian National Police, his left leg was so badly injured it had to be amputated.1 The police had shown up at his workplace in Venezuela the year before and arrested Roberto on suspicion of dissenting against the Maduro government. The threat of persecution became so imminent for their family that in October 2023, Roberto and his wife Elena packed a few belongings and fled with their sons. They had been building a life together in Caracas—their two sons were in their early twenties, on the verge of starting families, and pursuing their dreams. She was a street vendor and he was a car mechanic. They had no idea how drastically their lives were about to change.

Roberto and Elena walked for two months, across the Darién Gap and through eight different countries, in severe weather, to reach the United States and apply for asylum. By 2025, they would become two of the nearly 233,000 asylum seekers to come to New York City, in pursuit of a safer, more dignified life.

In New York City, thousands of asylum seekers and their children have spent the past two years living in shelters, often in undignified conditions, subsisting on unhealthy meals and contending with the threat of homelessness looming over their heads.2 Since 2022, New York’s main housing policy to support asylum seekers has been to provide temporary shelters, while slowly attenuating access for thousands and becoming increasingly unsustainable. Three years later, as of August 2025, about 35,400 of 233,000 asylum seekers continue living in city-funded shelters.

This report mobilizes the housing and employment experiences of fifty asylum seekers in New York to argue that state lawmakers should replace the temporary shelters and minimal social services currently available with robust housing assistance programs and joint housing–employment ventures, which can support asylum seekers with rebuilding their lives and improve the socioeconomic conditions in New York.

Figure 1

I interviewed fifty asylum seekers who have immigrated to New York City since 2022.3 They come from all over the world, and speak several different languages. All but five have either previously lived in or currently live in a NYC shelter.

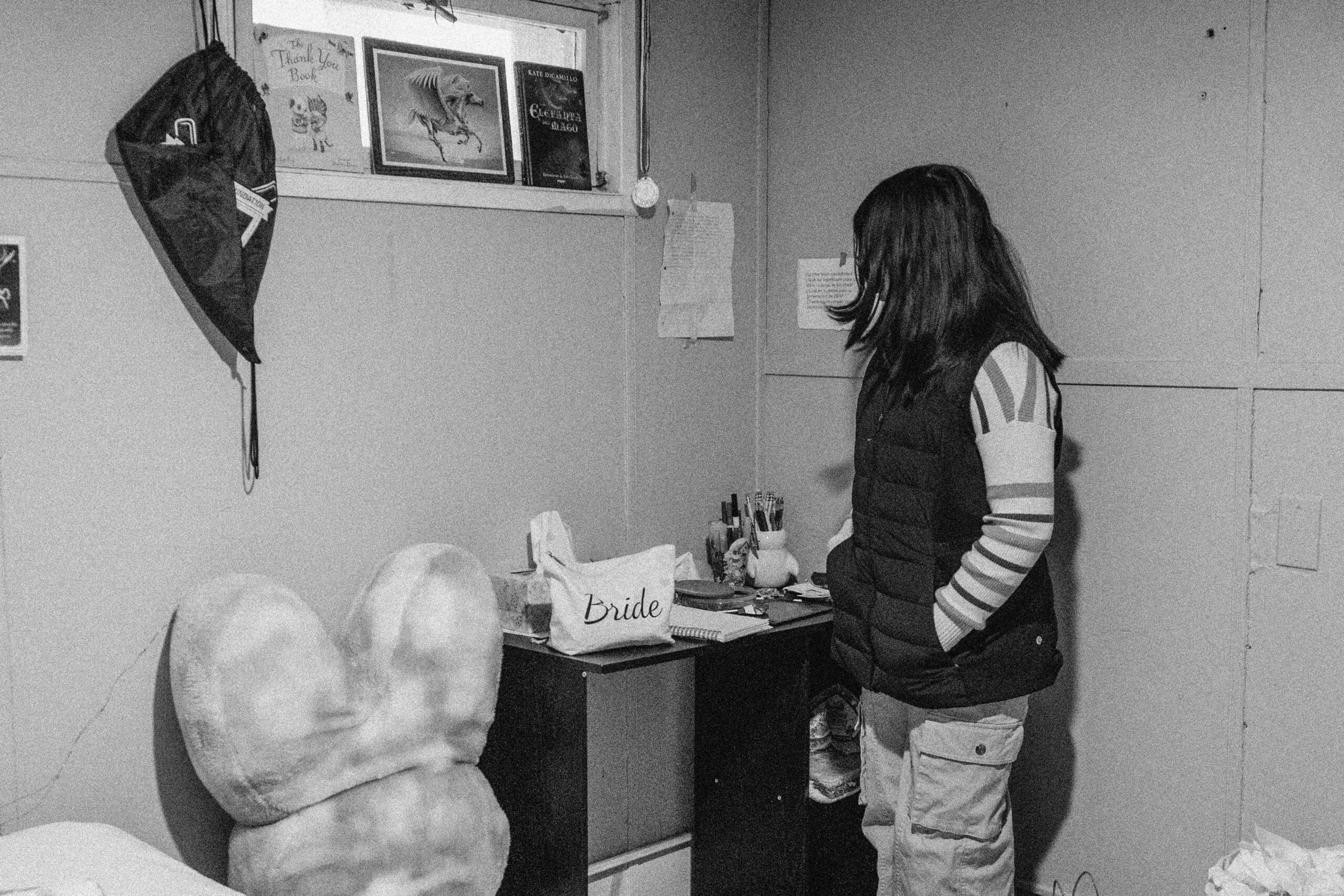

The images in this report are from a complementary, long-form photo project, including several participants from this research project. To protect participants from threats to their safety, the faces and identities of the photo participants have been obscured.

Demographic Overview

In the three years since 2022, the makeup of those seeking asylum in New York City has evolved. The number of new asylum seekers arriving in the city has decreased as the Biden administration tightened entry through the border, and as the current Trump administration rolled back Biden-era deportation protections and began a mass deportation campaign. Within the last year, the city closed sixty-two shelters dedicated specifically to asylum seekers, and relocated the remaining asylum seekers into New York homeless shelters. Currently, there are 35,400 asylum seekers in shelters, most of whom are families with children, and almost all of whom have been shuffled from shelter to shelter over the last few years.

Due to the city’s lack of transparency about the numbers of asylum seekers in shelter, it is difficult to disaggregate who remains in shelter by their family status. Of those interviewed for this report, 52 percent of respondents are members of families with children, 38 percent are single adults, 6 percent are part of adult families, and 4 percent are unaccompanied youth.4 The spread of respondents’ country of origin largely mirrors the actual distribution of asylum seekers in shelter.5 Most asylum seekers currently in shelter are from Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, and the Republic of Guinea (Guinea). In this survey, Guinea is overrepresented because Guineans are the largest African population currently living in shelter and this survey attempts to fill a gap in the existing research, which tends to underrepresent African asylum seekers.

Figure 2

Families with children represent 52 percent of respondents, while 38 percent were single adults, 6 percent were adult families (families with at least one adult child or without any minor children), and 4 percent were unaccompanied youth under 23, who were residing in youth shelters.

Work Permits and Employment

Like most asylum seekers, Elena obtained her work authorization as soon as she had the chance to do so. With Roberto’s life-altering injury and limited opportunities for employment, she had to find work to move their family out of shelter. However, even with work authorization (which takes months to arrive), there are no streamlined platforms for people like Elena to look for work, and postings are not always available in languages other than English. Additionally, when asylum seekers have job-matching opportunities, they are not always connected to jobs based on their skill levels and expertise, and have to rely on industry-specific job readiness workshops to gain access to openings. For example, several respondents stated that despite having training as scientists or having specialized work experience, they were pivoting to work as cooks, delivery workers, cleaners, or any other job that would hire them.

100 percent of respondents who have been granted asylum or social security numbers have applied for work authorization.

The lack of work compounds the challenges of housing instability for individuals like Roberto and Elena. In December 2024, Elena received a notice that the Hall Street shelter where they lived would be shutting down. “Yo estaba en un shelter,” she texted me, “pero, ya me desalojaron. Cumplí el tiempo, y no tengo donde estar. Ando en la calle.”6 They were required to leave the shelter by mid-December, and they needed to provide proof of an exigent circumstance, such as a debilitating medical condition, in order to reapply for shelter. Elena had been attempting to find stable employment for a year, with no streamlined process or systemic support. And without stable work, she was unable to find an alternative to shelter, which she so desperately wanted to do. Now, the threat of homelessness loomed over her, worsening the longer she went unemployed.

There is a common misconception that asylum seekers come to the United States only to rely on the government for “handouts,” and are neither expecting nor willing to work. Not only are most undocumented immigrants, including asylum seekers, ineligible for federal public benefits like food stamps, public housing, Medicaid, and cash assistance: this survey’s results also directly contradict this misconception about willingness and desire to work. When asked for how long they would want a government-funded housing voucher, 70 percent of respondents said they would only need a voucher until they found work to support themselves, and would rather have support finding work. One respondent said, “Yo no quisiera ser una carga para el Estado, la verdad. Yo quisiera que me den la oportunidad de poder trabajar y yo mismo pagar mis gastos.”7 Additionally, 100 percent of respondents who have received their Social Security numbers or have been granted asylum—meaning they are eligible to apply for work authorization—have applied for it. So, it is not the lack of enthusiasm for work, but rather the bureaucratic work authorization process and broken employment system that are holding asylum seekers back from becoming gainfully employed.

Figure 3

In this survey, forty-one respondents applied for work authorization, but only thirty-two respondents have received it. The nine who did not apply were ineligible to do so.

More than 65 percent of respondents have not found employment despite having a permit.

Between 2022 and February 2025, the city shut down twenty-five shelters. Residents received shelter exit notices and scrambled to find an alternative. By August 2025, the city shuttered sixty-four shelters, allowing only families with children under 21, families with a pregnant member, and single pregnant adults to apply for shelter with the Department of Homeless Services. All others were left without adequate alternatives for housing. Without a streamlined system for finding work and with limited affordable housing resources, asylum seekers have either relied on their own networks to find housing and informal work to stay afloat, or have stayed in the volatile shelter system while navigating unemployment.

Figure 4

Twenty-six respondents said they never found housing outside of the shelter. While nearly half received shelter exit notices and had to leave, all but three respondents reported being allowed to reapply—though they had to do so at a different site.

One third of respondents said they had experienced street homelessness at least once during this time.

42 percent reported that they received no help in their housing search.

Figure 5

Forty-two percent of respondents said they did not have any kind of help in their housing search.

Thirty-eight percent indicated that they relied on their friends or other asylum seekers who had come before them.

Thirty-two percent indicated receiving some support from nonprofit organizations, legal aid organizations, mutual aid groups, or religious organizations.

In September 2024, I met Liliana, a single mother with three sons, outside a shelter in Brooklyn. By November, she had received a notice to leave, and by December, she was relocated to a shelter in midtown Manhattan. Her oldest son, 27, left the state to pursue employment opportunities, and Liliana struggled to navigate keeping her youngest sons in school in a different borough. In March, I got a text from Liliana, “vivo en jamaica, me cambiaron.”8 She and her children had been relocated again, this time to Jamaica, Queens—an hour and a half each way from her sons’ school in Brooklyn. With the frequent relocations, Liliana struggled to build her support network: the instability made it harder for her to know which organizations to lean on for help with employment or housing resources.

Asylum seekers have often painstakingly built their support systems and communities in their new home city. The collateral consequence of the temporary shelter system and the thirty-day or sixty-day shelter exit policies is the disruption of these communities, or even the prevention of developing them in the first place. The volatility compels them to sporadically relocate to different boroughs, simultaneously starting over and falling behind in the process.

Figure 6

Of the forty-five respondents who had lived or currently live in a shelter, 47 percent reported that the case manager in their shelter did not help them with the housing search.

One respondent said they were unsure whether the shelter had any case managers, and four respondents reported that their current shelter in fact didn’t have one at all.

The city failed to help more than half the respondents with finding housing.

The bureaucratic, federally controlled work authorization process; the lack of a streamlined platform for finding work; limited multilingual posts; and continuous displacement from shelter every thirty to sixty days compound asylum seekers’ economic and housing challenges. For many asylum seekers, this means leaving the state to pursue employment and housing opportunities elsewhere. For New York, this means potentially losing the $2.7 billion that undocumented immigrants, including asylum seekers, pay each year in state and local taxes, as well as their contributions to the state and local labor market. Unfortunately, under the Trump administration, it will be difficult for New York State to implement a state-sanctioned work authorization process without altering the Constitution, given that the matter falls under federal jurisdiction; however, lawmakers have previously attempted to push one forward.

That said, even in the absence of a solution for the failures of the current work authorization system, state lawmakers can still implement programs to support asylum seekers with existing work permits by creating a streamlined and accessible employment platform, creating joint housing-employment ventures, and targeting tough-to-hire roles. The following section discusses these options.

Policy Recommendations

Create a Standardized Employment Hub

Recommendation: The city and the state should create a streamlined job search platform that integrates the NYS Job Bank, Jobs NYC, openings across all levels and sectors in the state, and job readiness programs that are pipelines to employment. This platform should streamline search functions by years of experience, locations, language requirements, skill levels, and sectors. It should also include an “easy apply” button, through which asylum seekers can apply to the job directly from the platform. This platform should be a web platform and a mobile application, and should be offered in the top ten languages spoken in New York, at minimum. For a successful rollout, this platform must be available on all computers at public libraries and be included as a resource at all asylum seeker service touchpoints.

The problem this would address: Currently, asylum seekers have to sign up for the state’s Career Assistance Request Form, only offered in English and Spanish, to receive information about prospective job opportunities. There are no streamlined job search platforms across New York City or the state that offer listings and applications in multiple languages and across sectors and skills.

The impact this would have: Streamlining the process to fill jobs will increase economic productivity and generate additional tax revenue for the state. Additionally, this platform would meaningfully connect thousands of potential employees to vacant jobs, increase the chances of upward mobility, and ensure that peoples’ skills and expertise are being maximized, rather than compelling them to accept jobs for which they are overqualified. Importantly, this integrated platform would not only be useful for asylum seekers, but also for all New Yorkers who may be searching for work across levels and languages. The investment will pay off exponentially.

Reimagine the Migrant Relocation Assistance Program

Context: In 2023, New York State launched the Migrant Relocation Assistance Program (MRAP) to offer rental assistance and social services to asylum seekers, who would agree to move to Suffolk, Westchester, Albany, Monroe, and Erie Counties. The program was budgeted to relocate 1,250 asylum seeker families, but only 640 families have relocated, and the majority of the funding remains unused. Initially designed to target the growing asylum seeker population in shelters, MRAP shuttered in June 2025, as the shelter population decreased from its peak of 69,000 to about 43,000.

Recommendation: The state should re-establish the Migrant Relocation Assistance Program (MRAP) and widen its scope. MRAP was underutilized and did not meet its targets within two years. The program should be expanded to fund housing vouchers for asylum seekers, regardless of the city in which they choose to reside. Moreover, the state should not wind down the program without reallocating funds to support permanent housing for asylum seekers.

The problem this would address: The recent shelter closures have caused thousands of asylum seekers to become unhoused. Additionally, there are 43,000 asylum seekers still remaining in the city’s homeless shelters. For all of these individuals, the voucher would be a crucial ticket out of a cycle of displacement and homelessness. Using the reallocated MRAP funds as vouchers would not only allow thousands a chance at a dignified quality of life, but also prevent the city from spending millions more on temporary housing.

The impact this would have: If MRAP were remade as an expanded housing voucher, thousands of families with children and individuals who continue to live in temporary housing would benefit. This would be the case even though the shelter occupancy numbers have fallen from their peak. Moreover, widening the scope of the program to include all cities in New York State will allow more asylum seeker families to qualify for the housing vouchers.

Furthermore, in shelters where families with minor children live, there are stringent rules about parents leaving children under the age of 18 without supervision, even if a friend offers to watch them. Having access to the safety of a home will allow parents to find community-based child-care or babysitting services, and enable them to go to work and become financially independent. MRAP 2.0 could be integrated into the Work Plus Program described below.

Launch a New Work Plus Program

Recommendation: New York State should create a dual employment and housing program to attract asylum seekers to fill positions in parts of the state with worker shortages, such as in health care, child care, K–12 schools, and skilled labor sectors. The state should offer multi-year housing subsidies, one-year housing vouchers, and one-year rent-free housing to asylum seekers through a joint program that pairs them with housing and employment in “hard to fill” positions. Local taxes generated from these jobs will help the program pay for itself once it is up and running.9

The problem this would address: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce reports that New York has ninety-five available workers for every 100 open jobs. The state’s construction industry and health care sector, among others, is facing labor shortages, and employers have had to increase wages and benefits to attract workers.

The impact this would have: This dual program offering employment and housing will attract specialized workers to areas of New York State that badly need them, and where workers might otherwise not go. While addressing the state’s labor needs, the program can simultaneously and effectively address the housing crisis faced by asylum seekers in densely populated areas like New York City by expanding their housing options. Moreover, this program is an excellent long-term investment, as increased labor force participation from asylum seekers will add to their purchasing power and tax contributions to the state. Importantly, such a dual housing and work program can offer asylum seekers a built-in community and support system as they build their lives from the ground up in a new hometown.

Conclusion

New York City is at the nexus of a large and complex housing system, molded and remolded by private and public interests and in the thick of an affordable housing crisis. New York City’s role as an historic hub for immigrants and asylum seekers has also put the city in the crosshairs of the Trump administration. State and city lawmakers should take advantage of the current federal political moment by focusing its investments on permanent housing and employment policies for asylum seekers. The former is less costly than shelling out billions in temporary shelter management, and the latter is an investment in expanding the city and the state’s economies that would capitalize on the spending power and tax revenue of thousands of new employees. These measures will create a safety net for the state in the event of federal funding freezes, and help New York become financially self-sufficient.10 Above all else, policymakers should support our newest New Yorkers with sustainable housing and economic policies not only because it’s good business, but because they should be in the business of doing good.

Photo Credit: Rudrani Ghosh

- The names of all people featured in this report have been changed for their safety.

- In May 2024, the Adams administration implemented new thirty-day and sixty-day shelter rules, which limit the number of days that single adults and adult families can stay in shelter, respectively. As a result, hundreds of asylum seekers were not only rendered homeless, but were also shuffled between shelters in different boroughs, causing them to be uprooted from communities and schools.

- All survey interviews were conducted in the native language of respondents, including in Spanish, French, and with an interpreter in Fulani, Pulaar, and Wolof.

- Between 2023 and 2024, 2,873 unaccompanied youth sought asylum in New York City, according to an estimate from the City Council’s Committee on Immigration. Further research should be done to understand the gaps in the systems supporting unaccompanied youth.

- Venezuelans represent more than 30 percent of the existing shelter population; they represent 20 percent of this survey’s respondents.

- Text translation: I was in a shelter, but they evicted me. I finished my time here, and I have nowhere to be. I am in the streets.

- Translation: I don’t want to be a burden on the government, honestly. I want to be given the opportunity to work and to pay for my own expenses.

- Text translation: I live in Jamaica now, they moved me.

- For example, the instrument sterilization technician position is one of several health care jobs with a high demand for personnel, and yet employers have encountered challenges filling them. The Wall Street Journal reports that one tech at a New York City hospital makes $34 per hour, or $70,720 annually. I used ChatGPT to estimate that there are about 700 openings listed on ZipRecruiter for this position. The state could earn upwards of $2.4 million in taxes just in one year by incentivizing asylum seekers to take these positions. Let’s take Kingston for a local example. In Kingston, where the cost of a one bedroom is about $1,200 per month, there was a concentration of forty-six technician openings. Kingston’s tax revenue from these positions in the first year, assuming all positions are filled, would be $160,586. This could pay for a three-month housing subsidy ($3,600/person) for forty-four people. By the following year, Kingston would not only recoup the costs in taxes from this position alone, but would also invigorate the rental market by allowing asylum seekers to save up capital to their own place.

- Acknowledgements: This project would not have been possible without the support of the Manny Cantor Community Center and Educational Alliance, El Puente, and Afrikana. A very special thank you to Papa Babacar, who provided hours of translation and research assistance to ensure that respondents speaking in Pulaar, Wolof, Fulani, and French were authentically heard and represented. And, my sincere gratitude to Shamier Settle from Immigration Research Initiative and Sam Stanton from the NYC Comptroller’s Office for their time and feedback on this report. Lastly, a big thanks to every respondent who shared their opinions and their lived experiences despite the traumas, infrastructural challenges to get to interviews, and the risks to personal safety, so that policymakers and I could learn from you: Your time and courage will hopefully pave the way for better protections and resources for asylum seekers across the state.