We Are Not Collateral Consequences: Children of Incarcerated Parents

Children of incarcerated parents are some of the most resilient children, profoundly impacted by a justice system that hardly acknowledges us. It is time to share our voices and our experiences of the consequences of our unjust system, so that we can lead the way to meaningful reform.

Throughout my life, a short twenty-three years so far, the public debate around our criminal justice system has covered everything from arrest to reentry. Our discussions have gone from “tough on crime” to “smart on crime,” and everything in between. We are seeing a (hopefully) transformative shift from over-incarcerating to using alternatives to incarceration.

But through all of these discussions of the criminal justice system, the children who ultimately live with the consequences of their parents’ incarceration are overlooked. I felt this through my own experiences with the justice system, when my own mother was incarcerated in a state prison when I was 7 years old. There was very little support provided for me as a child of an incarcerated mother, and the resources that were provided were limited—monthly Girl Scout trips to visit my mother, and some tribal resources upon my mother’s release.

I have since learned that these gaps in support weren’t unique to my experience. These are massive systemic holes in how we support the children of incarcerated parents (COIP). And furthermore, there are equally systematic ways that federal and/or state policy can support these young people. But first we as a nation have to recognize that these children exist—and that, without action, they will keep living with these harmful consequences of incarceration every day.

Children are often thought of as collateral consequences to our parents’ incarceration. But we are not fines, fees, jobs, or housing. We are our own people, who are early in our own lives. We also deserve resources and opportunities to succeed. We, as children, can’t be an afterthought; and we as a society need to start rethinking the way we provide resources, support, and opportunities to our population.

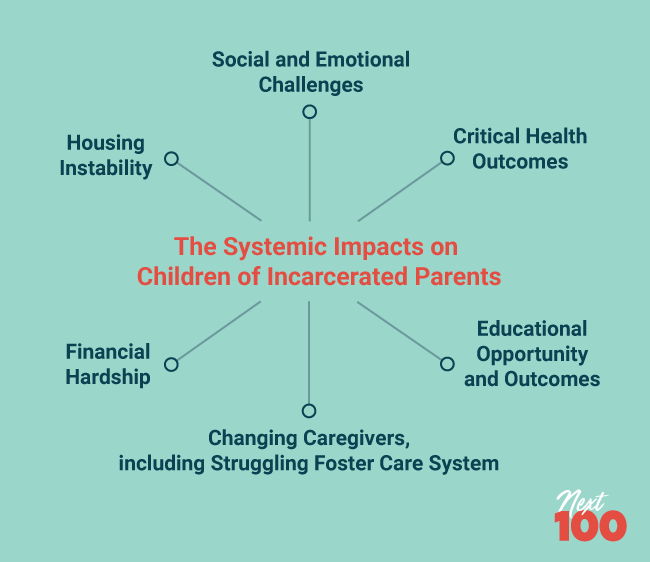

In this article, I will give a brief overview of the ubiquity of children with incarcerated parents, and summarize many of the negative repercussions with which the lack of public support and thoughtful public policy has saddled them. I am also concurrently publishing a set of three interviews with three COIP about our experiences as COIP—please check them out here! Quotations from those interviews are used throughout this article.

The Numbers Are Greater Than You Think

According to fwd.us, an immigration and criminal justice reform advocacy organization, 45 percent of adults have or have had an immediate family member incarcerated for at least one night in either jail or prison. And many of those who are incarcerated are parents: in state and federal prisons, about 45 percent of men age 24 or younger are fathers. For the same age group, about 48 percent of women in federal prison, and 55 percent in state facilities, are mothers. This means that many of the children left behind by parental incarceration are under the age of 18. In fact, more than 2.7 million children in the United States have a parent who is incarcerated. That means 1 in 28 children have an incarcerated parent, compared to 1 in 125 just twenty-five years ago. About two-thirds of these children’s parents were incarcerated for nonviolent offenses.

Very rarely do we think beyond the incarcerated person themselves when we discuss who is impacted by incarceration, but for each of those incarcerated people, their whole community and family are at stake, and their children are particularly impacted. As we can see from the above data points, the number of those impacted children is staggering.

The Communities—and Kids—At Stake

The racial and ethnic disparities within our criminal justice system are—finally—well-known. For Native-American and African-American communities, the impact of incarceration is extraordinarily broad. Sixty-three percent of Native-American and African-American adults—almost two out of every three people—have had an immediate family member spend at least one night in jail or prison. For Latinx communities, the proportion is 48 percent. African-American adults are nearly five times as likely as white adults to experience incarceration, and on average receive much longer sentences. Native Americans are incarcerated at rates 38 percent higher than the national average. African Americans are seven times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than are white children, and Latinx children are twice as likely. According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the data for Native children of incarcerated parents is not known nationally, but in Oklahoma, data shows that Native children are twice as likely as white children to have an incarcerated parent; while in both the Dakotas, they are about five times more likely.

The core trends are abundantly clear: while the outcomes of incarceration have been devastating for everyone imprisoned, communities of color have been particularly hard-hit.

As an Indigenous woman, I know the harms incarceration has caused my community in greater detail, and so I will share some insight into Native people’s particular challenges.

The unique set of systems governing and supporting Indigenous people includes tribal courts, tribal resources, and the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). All of these are systems that impact tribal children, and so these systems, just like those children, need adequate support. Tribal courts are especially challenged, as not all tribes have them, and the ones that do have tribal courts, do not have the full powers to operate within their full right. The federal government partakes in tribal courts and set certain restrictions in which tribal courts can operate: this means, for instance, that tribal courts cannot prosecute non-tribal members who commit a crime on tribal land. One consequence of tribal courts having their oversight so circumscribed is that in many jurisdictions, tribal members may have to serve in federal prisons, which can lead to them being relocated anywhere in the United States, far from their nation’s territory and their families.

Tribal resources such as housing, health care, and education are some of the services which tribes provide their enrolled tribal citizens. Some tribes are taking innovative approaches to helping incarcerated or formerly incarcerated tribal citizens. (Check out my tribe’s reintegration program here). ICWA was created to keep Native children in their communities, but the requirement to notify the tribes when a Native child enters the child welfare system is not always followed. These failures of the child welfare system leave many tribal children living outside tribal jurisdictions and, most importantly, outside of their culture and traditions.

When we discuss children of incarcerated parents, I want to make sure all children—including Indigenous children—are getting their needs met. And in any case, understanding the disparity of impact that the numbers in this section illustrate is imperative to understanding the picture of incarceration’s impact as a whole. The disparities in how communities of color are impacted by incarceration must not be papered over: instead, they need to be the starting point of our solutions and reforms.

Social and Emotional Impact on COIP

There are numerous areas in which we can see the impact of parental incarceration on children. Social and emotional impact is one such area that is important to acknowledge, understand, and address. Children experiencing the trauma of forced separation from their parent or parents due to incarceration may struggle to express their feelings about the loss of their parent(s), or may be stigmatized by their friends or by society. 25.5 percent of COIP report being socially isolated, compared to 9.4 percent of children who are not COIP. When society learns about the incarceration history of the child’s parent(s), that stigma and judgment is then passed on to the child. A study found that children were at risk of social exclusion due to stigma related to parental imprisonment and that they were punished because they did not participate in social activities. The transfer of guilt is not something a child should take on as a result from the criminal justice system—putting aside whether that judgment is appropriate in the first place. We must stop assigning guilt to children, who have no control over the situation.

Trauma is prevalent, explicit, cumulative, enduring, painful and generational.

According to the Public Health Association, the trauma endured from having an incarcerated parent is considered an adverse childhood experience (ACE), a category of adverse early life experiences that includes a death in the family, parental divorce, abuse, and neglect. Depression and anxiety, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (an anxiety disorder), are associated with having an incarcerated parent. Alexandria Pech, one of the children of incarcerated parents I spoke with and who works with the children of incarcerated parents, explains, “In my personal experiences working with COIP across different capacities, I have observed how trauma is prevalent, explicit, cumulative, enduring, painful and generational. Research has started to look at how parental incarceration influences identity formation among COIP such that stigma, shame, and dehumanization are common feelings that COIP have to navigate through.”

Educational Impact on COIP

Education can be key to breaking the intergenerational cycle of incarceration; but the children of incarcerated parents face many different challenges that can get in the way of their educational success. Visiting a parent on weekends can make it hard to focus and spend time on school work, causing grades to drop (which is not a reason to discontinue parental visits!). On the flip side, children who excel academically, children who—for whatever reason—may not want to be associated with their parent’s incarceration and are exceling, are also rarely talked about. The spectrum of how COIP perform at school needs to be taken into account—and not solely to stigmatize COIP students as low performers. The lack of resources for the incarcerated parent to be involved in their child’s educational attainment can be challenging: for example, communication between teachers and incarcerated parents about a student’s progress and success is made extremely difficult. From personal experience and from speaking with many other COIP, the need for more support at school, and with discretion for the student’s privacy, is important for children to feel comfortable to disclose that their parent is incarcerated to teachers or school counselors. Too often children are lying about the absence of their parents for fear of being stigmatized, and they have a right to feel this way, as that stigmatization is all too common.

These negative consequences for a student’s education can extend across many types of academic outcomes. For example, 50 percent of COIP students had poor grades or instances of aggression (though many of these were temporary). One study showed that just 2 percent of children with an incarcerated mother earn a college degree. Any meaningful reform to our education system needs to include training and additional resources for teachers and school staff who instruct and work with COIP. Alexandria Pech attests to this need, describing her experience about the dual feeling of being policed both while visiting her dad in prison and while at school: “One time, I was forced to take out a small piece of wire in my bra in the bathroom with nothing to cut with but my hands. This was dehumanizing as they made me feel like I was a criminal. In school, I was visibly a Brown girl, and my clothing was also policed by teachers.”

Foster Care and Caregiver Impact on COIP

A parent in prison means that COIP must be placed in safe care—and all too often, that care must be given by someone who isn’t related or even previously known by the child. Therefore the foster care system in general, and the caregivers the system selects for COIP in particular, have critical impacts on COIP’s lives. It is frequently too legally confusing or overwhelming for relatives or family friends to obtain custody of the child, even when they want such custody. And even when they are able to do so, that child is still no longer in the home they are familiar with—an additional barrier to overcome. At least 4.5 percent of foster children are in foster care because a parent is incarcerated.

Federal policy makes this already challenging situation worse. The 1997 federal Adoption and Safe Families Act, while in theory designed to assist children without parental support, in practice frequently and permanently severs the parent–child relationship. The legislation requires states to file a petition to terminate parental rights on behalf of any child who has been in foster care for fifteen months; but the average prison sentence is longer than fifteen months, especially over the past few decades of “tough on crime” policy. At least 32,000 incarcerated parents since 2006 have had their children permanently taken from them, with poverty as the official “main factor.”

Caregivers—grandparents, aunts and uncles, siblings, and members of the larger community—are placed in a critical role to help the child adjust to their new life circumstances while at the same time navigating being a caregiver—sometimes for the first time, but always for one more child than they had planned to be able to provide for. Currently there is a huge lack in support for caregivers as they take on these additional responsibilities—both financially and mentally. Zaki Smith, a colleague of mine at Next100 and also a COIP, explains, “We eventually went to stay with my grandmother for the whole time my mother was locked up, which turned out to be about ninety days. I never had a space to talk to anyone about my mother’s incarceration.There wasn’t any support for my grandmother, who automatically became our caregiver. It was a thing we weren’t allowed to talk about—it was viewed as my mother’s personal business.”

Of course, all this puts a huge strain on the parent–caregiver relationship, which ultimately impacts the parent–child relationship as well, making relations once the parent has been released even more difficult. A huge indicator of a child maintaining a relationship with their parent during their incarceration is a positive relationship between caregiver and parents.

Financial Impact on COIP

The moment a parent is removed from a child, that child is at an economic disadvantage because a portion—or all—of their household income has been removed. A study found that in the period that their father was behind bars, the average child’s family income fell 22 percent, compared with that of the year preceding the father’s incarceration. Upon a parent’s reentry, children are still at a financial disadvantage, because of the collateral consequences of incarceration that impact employment and stable housing. The formerly incarcerated have to navigate the system to find a job that accepts those that have a criminal record, and the truth is that not many do. In fact, the legal barriers to employment and other aspects of a stable life that formerly incarcerated individuals face numbers in the thousands. Zaki notes how difficult it is to be blocked “from employment, housing, and other opportunities that can support a successful re-entry. This can have a long-lasting impact on families, especially children. The inability to find work, the inability to take care of your family—many young people take on that pressure, fearing that their parents may resort back to the thing that got them locked up in the first place. And oftentimes that is the case.” These barriers apply to so many factors that are critical for the parent’s—and the child’s—livelihood and well-being, from housing to education. (To learn more, check out this article by my colleague Zaki on the collateral consequences of incarceration faced by formerly incarcerated individuals.)

Prisons are often in rural areas, and a report showed 63 percent of people in state prisons serve their sentences in facilities more than 100 miles from home. For federal prisons, the average distance is 500 miles or more—and it is not uncommon for people to serve their sentences outside of their home state. Imagine, on top of everything else, how expensive it is for a child to see their parents—and for only a few hours at a time at that, if they’re lucky.

Health Impact on COIP

The health consequences of having an incarcerated parent can be devastating, and range from physical health factors to mental health factors. This can include increased risk of teenage pregnancy, STDs/STIs, increased emergency care visits, and mental health challenges (as I outlined above).

One issue that is often missing from the conversation about COIP is the topic of sexual health. According to a Duke University report, 14.3 percent of COIP become teenage parents, five times as many as their non-COIP counterparts (for whom the rate is 2.8 percent). Today’s barriers to birth control for children under 18—even with a parent’s consent—are substantial. It is extremely difficult for any young person to navigate the health system—whether that be, for instance, understanding co-payments and deductibles, the laws around abortion, or parental and pediatric care—to protect their bodies; and doing so with an incarcerated parent who is unable to offer emotional or physical support makes things even harder.

In an article in Pediatrics, researchers found that having an incarcerated mother during childhood doubled the likelihood of a young adult using the emergency department instead of a primary care provider. Furthermore, research shows that COIP have higher rates of asthma, HIV/AIDS, learning delays, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder—more research was stressed as necessary to specifically identify the barriers to health care. All of these gravely impact the child’s life into adulthood. Added support and resources are needed to increase the quality of COIP’s health, health that all children need as they grow up.

The Need for Change

This article has largely been about the challenges children of incarcerated parents face, particularly children under the age of 18. (Note: Children over the age of 18 face some of the same struggles and challenges. Please refer to another resilient COIP, Ebony Underwood from WeGotUsNow, who is raising awareness around all COIP and their needs.) In no way is this information meant to further stigmatize COIP, but rather look into the several challenges of being a COIP from a COIP’s own perspective. Many of these challenges are created or exacerbated by our criminal justice policies; but we can also use policy to address and counteract these challenges. These policies must support the many children impacted by the incarceration of their parents, or the harm will continue generation after generation, leaving our stories to be told over and over again.

Policies must support the many children impacted by the incarceration of their parents, or the harm will continue generation after generation, leaving our stories to be told over and over again.

The current criminal justice reform efforts should include support for the children impacted by incarceration, who are disproportionately children of color. In a follow-up piece to this one, I will give policy recommendations for children of incarcerated parents, from arrest to reentry. Please check back to the Next100 website for that piece soon—and in the meantime, check out these three interviews with COIP, including myself, for more insight into the obstacles and our resilience.