We Are Not Collateral Consequences: Policy Solutions for CIP, from Arrest to Reentry

Children of incarcerated parents face numerous systemic challenges that no child should be forced to experience. Here are nine policy solutions that will significantly reduce those challenges, and to the benefit of the children, their families, and all our communities.

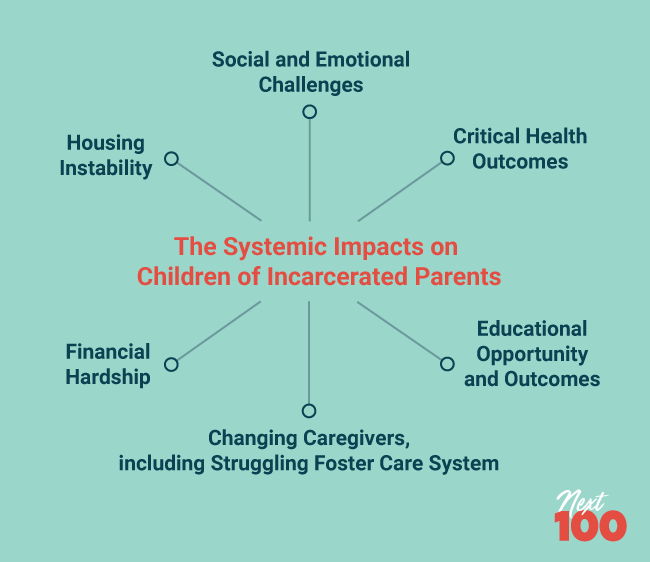

Finding the right solutions for the many traumatic challenges that children of incarcerated parents (CIP) face is not a simple issue, nor a small one. No child is alike, and so no set of experiences is exactly alike either; the same is true for communities and their needs. At the same time, we also know having an incarcerated parent is a major hardship that 2.7 million children in the United States face every day—that’s enough students to fill 5,100 average sized public schools. Faced with having a loved one bound up in such a complex bureaucracy as our prison system are numerous systemic challenges (more on this here), many of which were created by policy in the first place. Therefore what’s called for are policies designed with CIP in mind from the bottom up, policies that work together to give them the lives they deserve. This report includes a number of such policies that federal, tribal, state, and local policymakers can enact to support these children.

The author of this report is one of the ten million people who have been impacted by parental incarceration at some point in their life. I witnessed the arrest, sentencing, and imprisonment of my mother at the age of 7 years old. The impact of an incarcerated parent goes beyond just the time when a parent is incarcerated. After my mother was released from prison, she made the conscious decision to make education and raising me her priority. She had to deal with several barriers due to her criminal record that ultimately impacted me, like not qualifying for low-income housing, being blocked from volunteering at my school, student financial aid issues, and more. In spite of all these barriers, but not without immense hardship, my mom successfully completed her education which had a trickle down impact on me receiving my education. The systems we continue to live in today don’t make my story unique. I believe too many criminal justice reform efforts lack a central focus on the children of the people they are helping. Making children the focus will invoke more meaningful change and will have a ripple effect on their parents and communities. The criminal justice system simply rips our parents away without offering any meaningful supportive policy or services to fall back on—and that’s if we continue to separate children from their parents at all.

To be clear: The policy solutions presented below are not the structural changes that are needed to end mass incarceration, poverty, or racism, nor the Jim Crow era of criminal justice policy we are currently living in. But that does not mean they are not worth doing. They are necessary changes that we can make immediately or in the near future, to minimize the effects of mass incarceration on children—from changing the way CIP experience the arrest of their parents, to lack of educational opportunities and counseling services, among the many other policy gaps and solutions I lay out in this report. These are solutions meant to address the oppressive system children encounter once our parents come into contact with the criminal justice system. I would also like to also point out the political momentum to decarcerate, impose less surveillance, and mitigate contact with the criminal justice system. Our solutions to the criminal justice system should not rely on further surveillance of people, but instead include community support and services to elevate people to achieve the success they want in their respective lives.

This report includes a series of policies that the federal government, tribes, states, and localities can implement to better support these children. Some of these solutions have come from existing programs/policies that states and/or local communities are implementing, and some from the input and ideas of resilient CIP, including myself. I would like to point to a list of New York state based policy solutions created through a listening session that included myself and ten other children of incarcerated parents held by the Osborne Association. Collectively, they are meant to address the systemic challenges that CIP experience. (If you would like to read the prequel to this report that includes more information on these challenges, as well interviews with COIP, see here.)

In this report, I identify nine separate areas in which we must better support CIP through their parent’s arrest, sentencing, incarceration, and re-entry, including the social, emotional, and physical aspects of each. For each area, I have identified potential policy solutions that various levels of government can implement, including concrete models and examples where possible.

1. Children of Color and Cultural Support Essentials

Level: Local, State, Tribal, and National

Challenge: Children of incarcerated parents are disproportionately children of color.

Black children are seven times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than white children, and Latinx children are twice as likely. While the data for Native children of incarcerated parents is not known nationally, in Oklahoma, data shows that Native children are twice as likely as white children to have an incarcerated parent; in both the Dakotas, they are about five times as likely.

The criminal justice system has had multi-generational effects that continue to hit children of color hardest.

The criminal justice system has had multi-generational effects that continue to hit children of color hardest. As we put together policies to support these children, it’s time we create policies that are tailored to their needs and cultures, at every stage of the process; and ensure that the adults and systems with which they interact are culturally responsive.

Policies to Implement

Fund Inclusive Community Programs

States, tribes, and localities should create community services that provide to more inclusive programs for CIP with varying racial backgrounds, cultures, and community practices, and that provide counseling through art, sports, or other creative outlets. Additionally, these services should connect CIP to educational resources and aid in decreasing the shame they may experience from having an incarcerated parent, while also acting to decrease stigmatization in the broader community. Those programs are best run when staff mirror the people they are serving, which frequently requires training in how to be culturally responsive.

Provide Training to All Public Employees Who Come into Contact with CIP

To improve supports and outcomes for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx children, judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, teachers, principals, guidance counselors, social workers, and school officers, among other public employees should be trained in implicit bias; the nature of adverse childhood experiences (ACES), including the trauma caused by systemic racism; toxic stress and its impact on brain development; and the impact of separation for a child when a parent is incarcerated. Local, state, tribal, and national entities should provide funding for and require these trainings.

Prioritize Foster Care Placements within Children’s Respective Communities

No caregiver will be more culturally responsive to a child’s identity needs than one from their own community; so it is important to ensure that, if foster care must be used following a parental incarceration, the child is placed within their respective community if possible. Here are two proposals which advance this crucial priority.

Maintain and strengthen the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA): The positive outcomes for Native children come from being within their community and not transplanting them to a foreign one. Research found that 25–35 percent of all Native children were being removed; of these, 85 percent were placed outside of their families and communities—even when fit and willing relatives were available. By strengthening ICWA, Congress can help to ensure and enforce that Tribal nations have the authority to guarantee that the children of their Tribe are protected.

Fully support the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA): This long- overdue federal legislation transforms the foster care system. Enacted in 2018, the bill isn’t expected to be fully implemented until 2027. The bill seeks to avoid removing parents from the family setting during arrest whenever possible, provides support for kinship (relative) caregivers, and improves services for older foster youth up to age 23. The restructuring of the foster care system that will occur as a result of the bill will make very important progress in curtailing structural racism.

2. Data Reform: Gathering the Necessary Data and Keeping Those Most Impacted at the Forefront

Level: State and Federal

Challenge: The data gathered about children of incarcerated parents does not paint the full extent of their experience. Although the most recent data tells us there are 2.7 million children with incarcerated parents, my experience says that’s an undercount; and the data is often not collected and disaggregated in a way that shows impact on the communities most at stake.

Currently the data tells us there are 2.7 million children under the age of 18 who have an incarcerated parent, a number which was not easy to arrive at. I know from working with prisons how difficult it is to gather accurate statistics. I also understand the fear many parents have of disclosing their children’s whereabouts because of the fear of social services getting involved and deeming the guardian’s residence unfit. That being said, disclosure and trust are important to getting the real picture of the crisis we are in.

Another challenge to the data collection is the lack of representation of those who are impacted. There is very little data on the Native American children who have incarcerated parents. Although the data collection for Native communities has added implications due to the various governmental approvals, it is critical that federal, state, and local governments continue to work on the government-to-government relationship with our Tribal nations in data collection. Here is a link to a great article from Prison Policy Initiative, that explains the nuances of collecting Tribal citizen’s data. In addition to the lack of data, there is very little input from the voices of those impacted in the process. Advisory boards, councils, and the like lack the representation of the children who have or are facing parental incarceration, nor do they include the input of their caregivers. Both are essential parts of adequately addressing the varying experiences of CIP.

Policies to Implement

Ensure Data Transparency, Equity, and Accessibility

Every state and federal prison during intake should have a system in place to safely report incarcerated people’s children, including their age and race/ethnicity. The information should be made public without identifying the incarcerated person themself. Every year a committee of auditors should evaluate the data and report out on the findings.

3. Making Children a Priority During Arrest

Level: Local, State, Tribal, and Federal

Challenge: Witnessing the arrest of one’s parents is a traumatizing and far too common experience: one study estimated that of parents arrested, 67 percent were handcuffed in front of their children, 27 percent reported weapons drawn in front of their children, 4f percent reported a physical struggle, and 3 percent reported the use of pepper spray.

(Unfortunately I was unable to find more recent comprehensive research on this issue; we do know arrest rates have gone up since that time). These incidences are traumatic, and have a long-term effect on a child’s life. You can read about my personal experience during my mother’s arrest here.

Policies to Implement

Protect Children during Arrest

Ideally, parents should not be arrested in front of a child under any circumstance; the federal government, states, localities, tribal police, and immigration authorities should put in place protocol to avoid it at all costs. When that is not possible, the Osborne Association put together a list of other actions they can take to minimize the harm to children during such a painful moment:

- At the beginning of every arrest, ascertain whether children are present as a first step.

- Ensure the safety, respect, and well-being of a child during the arrest of their parents.

- Allow for physical proximity or contact if appropriate. A child deserves to give a hug and kiss before departing from their parents during arrest.

- Allow parents to arrange child placement and aid them in making arrangements for their children.

Child-sensitive arrest protocols have been successfully implemented in several states and localities, such as San Francisco. You can find their policy here. The International Association of Police Chiefs also has a tool kit that you can find here.

Replicate the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD)

The LEAD program allows law enforcement to send individuals arrested for low-level drug offenses to treatment and support services rather than booking, charging, and holding them. Thus far, those who participate in the program have been 58 percent less likely to be arrested again than those who are put into the system. The LEAD program was originally enacted in 2011 in Seattle, and can be read about here.

4. Ensuring Sentencing Policies Take Into Account Parental Status and Responsibilities

Level: State, Tribal, and Federal

Challenge: Sentencing is a challenging time for children, as it sets the path for the future of their parents’ lives—and their own.

And yet, too often children are left out of the important decisions made about their parents, and therefore their needs are neglected during the process.

Sentencing a parent is hard enough on the adult, but a child’s own experiences throughout add another facet. Sentencing a parent to serve time in prison creates several potentially traumatic challenges for children, such as changing caregivers and schools, that can have a long-term impact on their physical and emotional health.

When a parent is removed, the child loses a core part of the normalcy in their life, and mental and physical health issues and financial insecurity frequently result.

When a parent is removed, the child loses a core part of the normalcy in their life, and mental and physical health issues and financial insecurity frequently result. Moreover, the simple fact of physical distance can be a challenge. Prisons are often in rural areas; one report showed 63 percent of people in state prisons serve their sentences in facilities more than 100 miles from home. For federal prisons, the average distance is 500 miles or more.

Read here for more background on the challenges faced by the children of incarcerated parents.

Policies to Implement

Include Children’s Perspectives through the Use of Family Impact Statements (FIS)

Involving the child in the decision making process about their care situation can help to ensure that the child’s best interests are taken into account. Family impact statements (FIS) allow children to make a statement of the challenges their parent’s incarceration would have on them. Policies requiring FIS should also consider how to hear from children too young to make a statement for themselves, and require courts to inquire about the parents’ responsibilities and roles as a part of sentencing. FIS should be expanded to include the child’s voice during other important decisions beyond sentencing: Illinois recently passed a bill that includes FIS at bail hearings, and urges judges to release parents whose children will be impacted on their own recognizance or reduce bail so parents don’t have to go without to provide for their children. The bill language can be read here.

Enact Parent and Caregiver Alternative Sentencing

It is possible, and far more beneficial for everyone involved, to use alternatives to incarceration when sentencing parents. Parent and Caregiver Alternative Sentencing programs aim to keep parents home with their child, under community supervision and with community resources that address the root causes of trauma. Judges should have the option to waive or defer sentencing within the standard sentence range, and consider on a case by case basis the use of community custody along with for treatment and other programming. Washington State started the Parent Alternative Sentencing (PSA) program in 2010, and thus far, the program has served 274 parents with alternative sentences; of those parents thus served, 92 percent have not been convicted again. In the past year, Washington has expanded eligibility to non-custodial parents and parents convicted of violent criminal history thus positively impacting more children. While Washington state has had it’s program in existence the longest and therefore has the data to show the success, other states have implemented parent alternative sentencing programs such as Oregon, Tennessee, California, Massachusetts, and Illinois. Most notable is the Massachusetts bill S. 2371 that seeks to divert parents without including the state department of corrections, which therefore prevent parents from coming into contact with the justice system.

Ensure Geographic Proximity to Children in Traditional Sentencing Placements

If alternative sentencing is not an option, then parents who are sentenced should serve their sentence in the prison closest to their child’s location. At intake, state and federal prisons should take into account whether an incarcerated person has a child, and value their proximity to them when determining prison placements. Legislators in New York State have recently passed a bill that would prioritize placing incarcerated parents near their child’s residence.

5. Keeping Children Connected to Their Parents: Maintaining Safe, High-Quality, and Long-Lasting Connections during Incarceration

Level: Local, State, and Federal

Challenge: Whether a parent is in jail or prison, and regardless of the length of the stay, it’s important that children be able to stay connected with them, through phone calls and in-person visits.

A report released from Forward Together, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, and Research Action Design, the result of a year-long survey of 712 formerly incarcerated people and 368 of their family members across fourteen states, finds that the costs of incarceration extend far beyond an incarcerated person: more than a third of participant family members had to go into debt to pay for phone calls and visits alone.

many jails only offer visiting through glass (non-contact), which is not sufficient to maintain and protect a parent–child relationship. This is very upsetting to children whose norm is to have physical contact with their parents.

Just as phone calls are an important means of staying in contact with parents, being able to see parents in person is equally or even more important for children. This seems like a simple request, and many jails and prisons already offer in-person visits. But many jails only offer visiting through glass (non-contact), which is not sufficient to maintain and protect a parent–child relationship. This is very upsetting to children whose norm is to have physical contact with their parents. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these crises, with more jails phasing out in-person visits altogether; furthermore, private-sector collaborations have frequently undercut this need, such as jails working with predatory companies to install video cameras that replace in-person visiting. These denials of contact can traumatize or retraumatize the children who experience them. Expanding programs that make space for parent–child connection, such as father/daughter dances or arts and craft programs, help lessen the cold experience of prisons, and make it easier for a child to engage with their parent. Staff can sometimes buffer the aggressive experience of prisons and can change the experience for the child, while maintaining safety at the same time.

The number of women being incarcerated has dramatically increased in recent years, and roughly one in twenty-five women entering prison are pregnant. An estimated 2,000 babies are born every year to an incarcerated mother. Even more alarming are the systematically unacceptable, but common health care challenges for both mother and child: the twenty-four hours mothers get to spend with their babies before being split up, lack of prenatal care and birthing practices, and lack of postnatal care. The long-term impacts on children’s mental health such as attachment disruptions and other health conditions are severe, and demand alternative protocols.

Policies to Implement

Provide Free and Accessible Phone Calls

All jails and prisons should ensure incarcerated people have free daily phone calls to their children and families, that are long enough to maintain a connection. While the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has prohibited the extremely expensive $1-per-minute phone calls that used to be common, the cost of calls should be removed altogether from the incarcerated person and their family’s responsibility. We Got Us Now, a national organization, released concrete policy to make phone calls free during the COVID-19 pandemic and after. You can read their recommendations here. Connecticut recently passed legislation that now takes the burden from incarcerated people and their families and provides free phone calls.

Make In-Person/Contact Visits Available

Some jails do not allow contact visits between family members and the incarcerated person, thus lessening the quality of the visit and requiring children to undergo another traumatic experience. All jails and prisons should ensure in-person visiting is a simple and accessible option for all children and their incarcerated parents.

Provide Child-Friendly Visits

Some prisons and jails throughout the country have implemented specific positive events for parents and children such as father/daughter dances, arts and craft activities, or even sleepovers for children to be able to spend the night with their parents. Not only is it important for the visit rooms to be child friendly, but the waiting areas and screening protocols should also aim to provide a child friendly environment. Those who come into contact with the children—such as correctional officers and administrative staff—should be trained on child friendly approaches when communicating with children. In New York State, a bill was introduced to ensure incarcerated people are able to be visited by family and others. The Urban Institute released an important report that outlines visit type, visit structure, frequency/length of visits, and many other recommendations for prisons to start integrating into their protocol to better serve children who visit their incarcerated parent.

Invest in High-Quality Prison Nurseries and Better Health Care for Pregnant and Incarcerated Women, including Banning Shackling during Labor

I can’t emphasize enough the importance of considering alternatives to incarceration for pregnant women such as the PSA (see above in the sentencing section). It is a travesty that babies are born in prison. That being said, until that is solved, we must ensure they can build a bond with their mother. Only seven prison nurseries exist throughout the United States. Expanding the number of such nurseries so that more mothers can stay connected with their babies, ensuring that they provide high-quality prenatal and postnatal care, and ensuring the mother has access to resources upon her reentry is crucial to the success of both mother and child. A Washington State program, Residential Parenting Program, has proven the most robust example thus far, providing early childhood educator support (it’s only facility to provide this support), parenting skills, and nutrition classes, and allows children born in the facility to stay up to thirty-six months (longer than any other program in the nation). The bill also prohibits shackling during labor, a practice that should be banned across the United States.

6. Long-Overdue Reforms of the Struggling Foster Care System

Level: State, Tribal and Federal

Challenge: Too often, the foster care system as we know it is severely struggling.

It has been struggling for decades because of disinvestment, inadequate oversight, and many abuses of power. The public servants who do try to make the system work must inevitably fail because the system itself is flawed.

Children of incarcerated mothers are four times more likely to stay for longer in foster care than those whose moms are not locked up. Most law enforcement agencies lack training and protocols on where to place children when a parent is arrested and incarcerated. Roughly 40 percent of incarcerated mothers and fathers fully met visiting criteria, compared to nearly 70 percent of non-incarcerated mothers and 60 percent of non-incarcerated fathers. At least 32,000 incarcerated parents since 2006 have had their children permanently taken away from them, with poverty as the official “main factor.” Such separations must be avoided however possible.

Policies to Implement

Fully Support the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA)

This was mentioned in my first set of policies to implement, but I want to reiterate the magnitude of the impact this bill would have on transforming the foster care system. The bill seeks to not only avoid removal from the family setting whenever possible, but also to provide support for kinship (relative) caregivers, and to improve services for older foster youth up to age 23. The restructuring of the foster care system that will occur as a result of the bill will be very important to changing the racism inherent in the system.

Update the Adoption and Safe Families Act

This bill passed in 1997 during the Tough on Crime era, and included provisions for incarcerated parents. The legislation requires states to file a petition to terminate parental rights on behalf of any child who has been in foster care for fifteen months; but the average prison sentence is longer than fifteen months. We need to update this cut off deadline to thirty-six months so more children can be reunited with their parents after their release.

7. Education: Improving Educational Support and Opportunities for CIP

Level: Local, State, Tribal, and Federal

Challenge: Children spend a substantial chunk of time in school—on average, thirty-four hours a week. That means teachers play a crucial role in all children’s lives, including CIP—but educators and our educational system are not always equipped to best support CIP.

Emotional development—which also happens in schools—is also important to a child’s development. And yet too often, CIP are not comfortable sharing their full selves at school. Time and time again I have heard of CIP creating cover stories about the whereabouts of their parents in fear of bullying, embarrassment, or simply not wanting to disclose their personal information. Furthermore, teachers are not the only ones in the school environment who play a critical role in CIP’s educational life: school nurses, coaches, after-school program leaders, pediatricians, and others who come into contact with them on K–12 campuses are key people in CIP’s lives. Too often, incarcerated parents have very little input or communication, if at all, with their children’s teachers, which results in low participation from incarcerated parents in their child’s education. Many schools discourage parents who have been justice-involved from volunteering at school events or field trips.

Too often, CIP are not comfortable sharing their full selves at school. Time and time again I have heard of CIP creating cover stories about the whereabouts of their parents in fear of bullying, embarrassment, or simply not wanting to disclose their personal information.

In addition, CIP often struggle to attend college and beyond: one statistic showed that just 2 percent of children with an incarcerated mother earn a college degree. Postsecondary education of any type—vocational, community college, or four year university—has a positive impact on long term outcomes.

Policies to Implement

Educator Professional Development

Teachers should be required to participate in professional development that enables them to understand the trauma induced when a child’s parent is incarcerated. The many external pressures a CIP student may face during this difficult time are important to understand if the teacher wants to know what might be creating any change in behavior or academic outcomes. Moreover, this professional development should be provided beyond classroom teachers, as children encounter many other professionals—coaches, administrators, social workers—who need the same training to understand the challenges CIP face. Ensure teachers (and people who come into contact with CIP) receive training from external organizations that bring expertise on implicit bias and the emotional, mental, and developmental challenges faced by CIP. Ensure teachers are supported by the administration to continue training as needed and are provided with any additional resources needed. Youth.gov compiled a tip sheet for teachers (pre-K through 12) on how to support children with incarcerated parents.

Foster a Supportive Environment

Ensure schools have a safe, affirming physical space for children facing toxic stress, with supportive and prepared adults, for students that is accessible both during and after school hours. Schools should find ways to encourage students who have faced a traumatic experience to have support and a safe place that is easily accessible at schools. One school in Yakima, Washington has created calm rooms. These helped children impacted by parental incarceration, depression, anxiety, and other traumatic experiences.

Enhance Financial Aid Opportunities

Increase funds for scholarships and financial aid to be awarded to children who have experienced parental incarceration. Creating scholarships specifically for CIP students would decrease disparities in educational attainment. CIP need resources to assist them in college attainment, and also need to receive emotional assistance and support while in school. While no governmental financial aid is specifically targeted at CIP, local organizations have sprung into action to help narrow the gap in services. ScholarCHIPS, for example provides college scholarships, mentoring, and a peer support network for CIP.

Enable Parental Involvement in Their Children’s Education, While in Prison and After Release

Schools should make it possible for parents to be involved in their children’s education while they are incarcerated. Moreover, this acceptance and valuing of the parent’s contribution should continue after the parent has finished their sentence, by allowing parents with records to volunteer and support their child at school functions. Ensure incarcerated parents have access to video conferencing so that they can participate in parent–teacher conferences and other one-on-one meetings with teachers, including receiving student materials such as report cards, behavioral updates, and newsletters. Ensure parents who have been justice-involved (including felons, but excluding those convicted of child abuse-related crimes) can volunteer at school functions and field trips. Ensure extracurricular instructors are included in the training sessions to aid in breaking down barriers to include school nurses, cafeteria workers, and school safety officers. The barrier for parents who have a criminal record impacts so many different factors in their lives. Several states are looking at legislation to enhance these opportunities, such as the Clean Slate Act, which would remove some of the collateral consequences of incarceration, including eliminating barriers to volunteering at a child’s school.

8. Health Care: Mental and Physical Health

Level: Local, State, Tribal, and Federal

Challenge: Health Care has proven difficult for CIP to access and afford, which puts their long-term health outcomes in jeopardy.

It is critical for CIP to have adequate health insurance and receive education and support around mental health, physical health, and sexual health. Too often, these are all lacking.

Children experiencing the trauma of forced separation from their parent or parents due to incarceration may have significant mental health needs that need support. Many may have a hard time expressing their feelings about the loss of their parent(s), or may be stigmatized by their peers or by other people around them in their daily lives. 25.5 percent of CIP report being socially isolated, compared to 9.4 percent of children who are not CIP.

It is extremely difficult for any young person to navigate the health system—whether that be, for instance, understanding co-payments and deductibles, the laws around abortion, or parental and pediatric care—to protect their bodies; and doing so with an incarcerated parent who is unable to offer emotional or physical support makes things even harder.

In addition, another issue that is often missing from the conversation about CIP is sexual health. According to a Duke University report, 14.3 percent of CIP become teenage parents, five times as many as their non-CIP counterparts (for whom the rate is 2.8 percent). Today’s barriers to birth control for children under 18—even with a parent’s consent—are substantial. It is extremely difficult for any young person to navigate the health system—whether that be, for instance, understanding co-payments and deductibles, the laws around abortion, or parental and pediatric care—to protect their bodies; and doing so with an incarcerated parent who is unable to offer emotional or physical support makes things even harder.

Policies to Implement

Ensure Funding for Free, Quality, and Accessible Counseling

Provide accessible and free counseling and therapy for CIP, through state or local entities. This can help with developing healthy coping and grieving mechanisms. Ensure the counselors and therapists are trained in working with CIP and go through implicit bias training.

Expand Medicaid Eligibility during Caregiver Transition and Provide Sufficient Funding to Navigate the System

It is simple enough for children when their parent is incarcerated is the transfer of eligibility of the medical insurance. Under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), many children are covered if they have an incarcerated parent. The issue is the transfer of coverage to a caregiver who makes too much or does not have the assistance to sign up for CHIP. This gap in coverage needs to be closed to ensure the optimal health of CIP.

9. Reentry Assistance

Level: Local, State, and Tribal

Challenge: The formerly incarcerated already have so many barriers to reentry, including housing, jobs, education, and transportation.

(See more on these 44,000 “collateral consequences of incarceration” from my colleague Zaki Smith here.)

Reentry is often spoken of after a person’s release from prison. In reality, preparation for reentry must start as soon as a person is sentenced because the end goal should be to set people up to live their lives with opportunities and resources, yet the 44,000 barriers mentioned above makes it so that this isn’t quite the reality we live in. An area where Tribal nations, and more specifically the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, has excelled is creating a gold standard reentry program that comprehensively helps incarcerated and formerly incarcerated citizens. It includes housing, job training, substance abuse counseling support, legal services, and much more. You can view a short video here.

Policies to Implement

Provide Continued Counseling and Therapy Resources

While counseling and therapy resources are necessary during incarceration, they must continue through release and parent–child reunification. It should begin twelve to twenty-four months prior to release, and last up to five years beyond release, given the extensive effects the criminal justice system has on incarcerated individuals, their children, and their relationships. Children shouldn’t feel the jolt of reunification: the experience should be a smooth transitional process beginning well before their parent’s release from prison.

Provide Funding for Navigating Release

Provide funding to support and guide parents to regain custody of their children, funding to aid in adjusting child support payments, and funding to aid in fine and fees. Supportive services should also include support to find jobs, job training, education support, housing, financial literacy, and child care.

Ensure Parole Officers Provide Support to Parents

Ensure parole officers support parents in resuming parental responsibilities, and provide parole officers with training to ensure they are able to do so effectively.

Replicate and Fund Clean Slate Legislation

Thus far, Clean Slate has been mentioned in state legislatures and first passed in Pennsylvania. The bill is meant to automatically expunge formerly incarcerated people’s records after a certain time period (tenyears in Pennsylvania law), thus reducing the barriers formerly incarcerated people endure after they have served their sentence. This is particularly important to the well-being of their children, who are also excluded from resources and opportunities when their parents can’t access them. My teammate Zaki Smith has done extensive advocacy work to pass the Clean Slate Act in New York State. You can read more about his work here.

A Call for Change

This report has sought to offer a comprehensive list of policy recommendations. Some of the recommendations have been implemented in some states, while other states are looking into passing these kinds of policies in some form. We need to jump-start more of these reforms all over the country, because children of incarcerated parents are at a crossroads. We can continue to move the needle on criminal justice reform and include CIP in the effort to do so, or continue down a path that is harmful to both these children and their communities. All children deserve equality and equity when it comes to the current criminal justice reform efforts.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my advisory board and those who provided input, feedback, and edits. Thank you for all you do and the work you do every day that supports CIP. Your work has led the way in many of these areas, and I am lucky to have you as advisors and partners in this work.

Advisory Members:

Ebony Underwood,is the founder/CEO of WE GOT US NOW, the first of its kind—a national nonprofit nonpartisan advocacy organization built by, led by, and for children and young adults impacted by parental incarceration with the mission to ENGAGE, EDUCATE, ELEVATE and EMPOWER this historically invisible population through the use of digital narratives, safe and inclusive spaces, and advocacy-led campaigns to ensure their voices are at the forefront of strategic initiatives, practices, and policies that will help to keep families connected, create fair sentencing, and end mass incarceration. .

Allison Hollihan, is the senior policy manager for the New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents, a special project of The Center for Justice Across Generations at the Osborne Association. Ms. Hollihan advocates for policies and practices that promote the well-being of children with parents involved in the criminal legal system by collaboratively working with the criminal justice, child welfare, education, and mental health systems in New York City and State, and nationally. Ms. Hollihan developed the Osborne Association’s video visiting program, which allows for children to visit with their incarcerated parents in New York through video in a supportive and child-friendly environment, and authored Video Visiting in Corrections: Benefits, Limitations, and Implementation Considerations for the National Institute of Corrections. Ms. Hollihan’s work is informed by her clinical background, collaborations with children and families, and the incarceration of her sister. She has over ten years of experience providing case management to child welfare involved families in Chicago, Illinois. Ms. Hollihan is a licensed mental health counselor and holds a MS in Urban Policy Analysis and Management from the New School.

Tanya Krupt has focused on addressing and minimizing the effects of incarceration on children and families for the past twenty years. She is currently the director of the Osborne Center for Justice Across Generations at the Osborne Association, which currently focuses primarily on two crises created by mass incarceration that remain largely invisible: children of incarcerated parents, and those aging in prison and returning to the community as elders. Prior to joining the Osborne Association in 2006, Tanya worked at the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS, NYC’s child welfare agency) where she helped start the country’s only program for children with incarcerated parents located within a child welfare agency. Tanya has also served as the family services coordinator in a medium security women’s prison in New York, and has a licensed master’s in social work (LMSW) and a masters in public health (MPH).

Tarra Simmons is an American politician, lawyer, and civil rights activist for criminal justice reform. In 2011 Simmons was sentenced to thirty months in prison for theft and drug crimes. In 2017, she graduated from Seattle University School of Law with honors. After law school, she was not allowed to sit for the Washington State bar exam due to her status as a former convicted felon, but she challenged the Washington State Bar Association rules in the Washington State Supreme Court and was allowed to take the exam. In 2020, Simmons was elected to the Washington House of Representatives for District 23.